Last year, we told you that Berkeleyside — the decade-old Bay Area news site that has proven to be one of online local media’s most sustainable publications — was looking to expand its model elsewhere. It was creating a new nonprofit parent organization called Cityside and launching its first sibling site next door, Oaklandside.

Nary a definite article to be found: Berkeleyside, Cityside, Oaklandside.

But when the new Oakland site actually launched yesterday, something both prominent and subtle had changed. Oaklandside was now The Oaklandside.Now I admit that I pay more attention to definite articles in the names of news organizations than, oh, 99.999 percent of the human population. I can tell you which newspapers make “The” part of their official name (and thus are capitalized) and which ones leave it as something for the reader to add mentally (and thus are not). For instance: The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, but the Los Angeles Times, the Chicago Tribune, the Houston Chronicle.

I’m the guy who’ll remind you that Politico actually launched in print as “The Politico.” Or why it’s “The Guardian” even though The Guardian’s own style guide says it’s not. (They’re just wrong.) Or how The New York Times Co. bought The Wirecutter in 2016, rebranded it as just Wirecutter in 2017, but kept the site at thewirecutter.com until last month and still occasionally slips up and calls it “The Wirecutter” (or “the Wirecutter”) in its own stories.

Yeah, I’m that guy. But that tiny shift to The Oaklandside carries a couple non-zero meanings.

First, it tells you that this is an outlet that will listen to its readers. I asked its editor Tasneem Raja why the change, and she attributed it to feedback from Oaklanders:

From our community feedback process! People just liked the way it sounded, and felt that it put the emphasis on showcasing and valuing what they love about Oakland. Telling Oakland's side of the story.

And thanks!

— Tasneem Raja (@tasneemraja) June 16, 2020

As the site’s about page puts it:

Our name, The Oaklandside, was chosen through a similar process of community listening with a wide and diverse range of Oakland residents, educators, artists, civic workers, and more. One participant told us this name suggests that “We’re on your side. We’re with you.” Another said, “It says that this is Oakland’s side of the story.”

The Oaklandside built listening into its pre-launch process to a remarkable degree. Journalists can sometimes assume they know what their audience needs — after all, we’re the professionals, right? The Oaklandside says it is “built on a foundation of listening”:

How do we build an outlet for local journalism that is rooted in, representative of, and responsive to communities in a city as diverse, complex, and powerful as Oakland?

That question was the North Star that guided months of work to build this newsroom. And finding the answer — a quest that will always, and should always, be a work in progress — requires a deep commitment to listening…

First, in order to produce journalism that helps people navigate their lives and understand what’s happening in their city, we must fundamentally understand what people care about and need more information on. Oaklandside staff members are each informed by their own experiences, and we can’t assume we know what’s best for all communities. We need to intentionally seek input from Oaklanders to make our reporting more relevant, accessible, and indispensable.

Providing clear opportunities for people to get involved in our journalism will help support a more informed, engaged Oakland.

Different outlets can do that in different ways — it does feel very East Bay to hold “a listening and printmaking event at the 2019 Life is Living festival” — but making that effort is critical to building and serving an audience, especially as a new brand in a place that manages to be both crowded and underserved at the same time.

You may, of course, have your own opinion about the relative merits of Oaklandside and The Oaklandside. But I tend to come down on the same side as this impressed reader:

Welcome. And I want to comment, that I very much like the use of the definite article in your name. "The Oaklandside" has exactly the right sound and feel, stronger and more immediate than simply "Oaklandside".

— Berkeleyan (@bswp) June 5, 2020

Putting a “The” in there evokes a kind of good newspaperiness — strong ties to its community, an institution with some civic weight — that you don’t get without it. Other than USA Today, just about every newspaper in America gets a “the” in common speech: the Times, the Journal, the Trib, the Morning News, the Star. “Did you see that story in the Post?” Meanwhile, digital news sites are much more likely to go article-less: BuzzFeed, Gawker, Vox, Vice. It’s not a coincidence that “the” is a more common prefix for digital sites that feel more local and place-specific: The Texas Tribune, the New Haven Independent, The Nevada Independent, The Tyler Loop (which Raja co-founded). The Oaklandside feels tactile in a way Oaklandside doesn’t.

And as those Oakland residents said, combining The and -side more explicitly positions your outlet as an advocate for the city and its residents. Not in a partisan way — in the way that many great 20th-century newspapers saw part of their role as making their city a better place.

Second, adding the “The” (not the The The) tells you that this is an outlet that is willing to adapt.

Berkeleyside is a strong and successful local news site, run by smart people. After announcing your new initiatives as “Cityside” and “Oaklandside,” it would have been extremely easy to discount anyone who said your name could use a tweak. That kind of resistance is an intensely human response, pride of ownership: Are you seriously trying to tell me I’ve been naming my site wrong for the past TEN YEARS, bub?

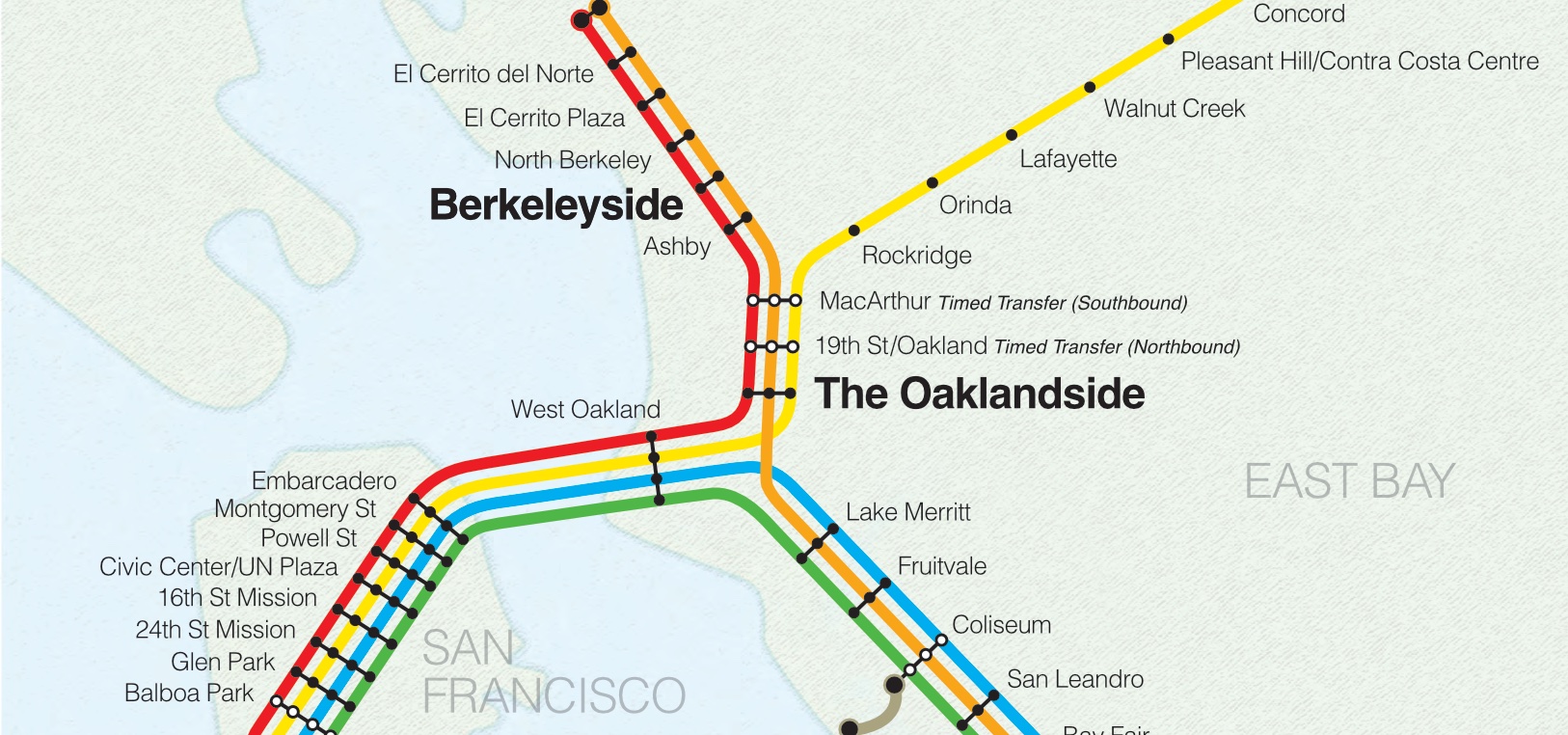

But Berkeley is not Oakland, and the name that’s optimal in one place might not be in another. As of the 2010 census, Berkeley was 60 percent white, Oakland about 30 percent; it would be very easy for Oaklanders to view a new site as an interloper, someone strolling down the MacArthur Freeway from its lefty neighbor to the north.

Berkeleyside launched in 2009 and I have to assume there weren’t a lot of community-printmaking sessions at local festivals before it settled on a name. If you’d asked me a week ago, I would have guessed that “Berkeleyside” was probably some old nautical term used by sailors trying to navigate the Bay. The site’s intro post put it this way:

Why Berkeleyside? We’re pro-Berkeley, we like our side of the Bay and we thought it had a nice ring to it. We’re Berkeleyites, but we’re also Berkeleysiders now.

The Berkeley side of the Bay and the Oakland side are the same “side.” But the view can look awfully different depending where you’re standing. Being willing to adjust your thinking to better serve your community is The lesson here.