A report commissioned by The Philadelphia Inquirer found that its coverage overwhelmingly featured people who were white and male. Sourcing and editing practices that catered to an imaginary print reader were at least partially to blame.

The report — by two professors at Temple University’s Klein College of Media and Communication, Bryan Monroe and Andrea Wenzel — looked at nearly 3,000 stories over six randomly selected weeks between August 2019 and July 2020. They found that white reporters tended to cover white people the most, but that white individuals accounted for 58.8% of individuals featured across all coverage, regardless of the author’s race. (This, in a city whose population is 42% Black.) In their executive summary, Monroe and Wenzel point to one reason why:

Conversations with newsroom staff and management illustrated how sourcing norms and editing traditions favored an imagined print reader who was older, whiter, wealthier, and more suburban. This lens took a toll on story selection, framing, and style — but also on the experiences and morale of staff, particularly on staff of color.

After in-depth interviews with members of the newsroom, the researchers concluded that journalists’ desire to produce more inclusive coverage “was complicated by perceptions of The Inquirer’s audience.” Some of the audience assumptions are largely correct — the print publication does have an older and whiter audience than the population of Philadelphia as whole — but others were not. (Digital-only readers are more likely to be suburban than print readers, for example.)

“Some editors acknowledged that the continued emphasis on a print publication was a barrier to coverage appealing to more diverse audiences,” the report states. This emphasis had far-reaching implications. Journalists of color shared experiences with editors “where assumptions about the imagined reader’s whiteness had forced them to alter their stories, adjust their style and framing, or not do a story at all.”

The external report was commissioned by The Philadelphia Inquirer after an insensitive headline (“Buildings Matter, Too”) sparked a wider conversation about a lack of racial representation in the newsroom and throughout coverage. Staff, led by journalists of color, declared they had been “dragging this 200-year-old institution kicking and screaming into a more equitable age” and 44 of them took a “sick and tired day” in protest. The Inquirer’s top editor resigned a few days later.The research released Friday consisted of an audit designed to “hold up a mirror” to existing coverage, one-on-one interviews, analysis of the staff’s demographic makeup, and recommendations to improve. Citing Wenzel’s previous work analyzing source diversity at WHYY as a model, the researchers identified 15,000 individuals who served as sources or subjects across Inquirer stories and other content, including photos, social media, and video.

[Related: Philly news outlets are collaborating to offer new kinds of Covid-19 coverage]

The investigation found that the Inquirer’s content consistently overrepresented white and male voices in a city where only one out of three residents is non-Hispanic white:

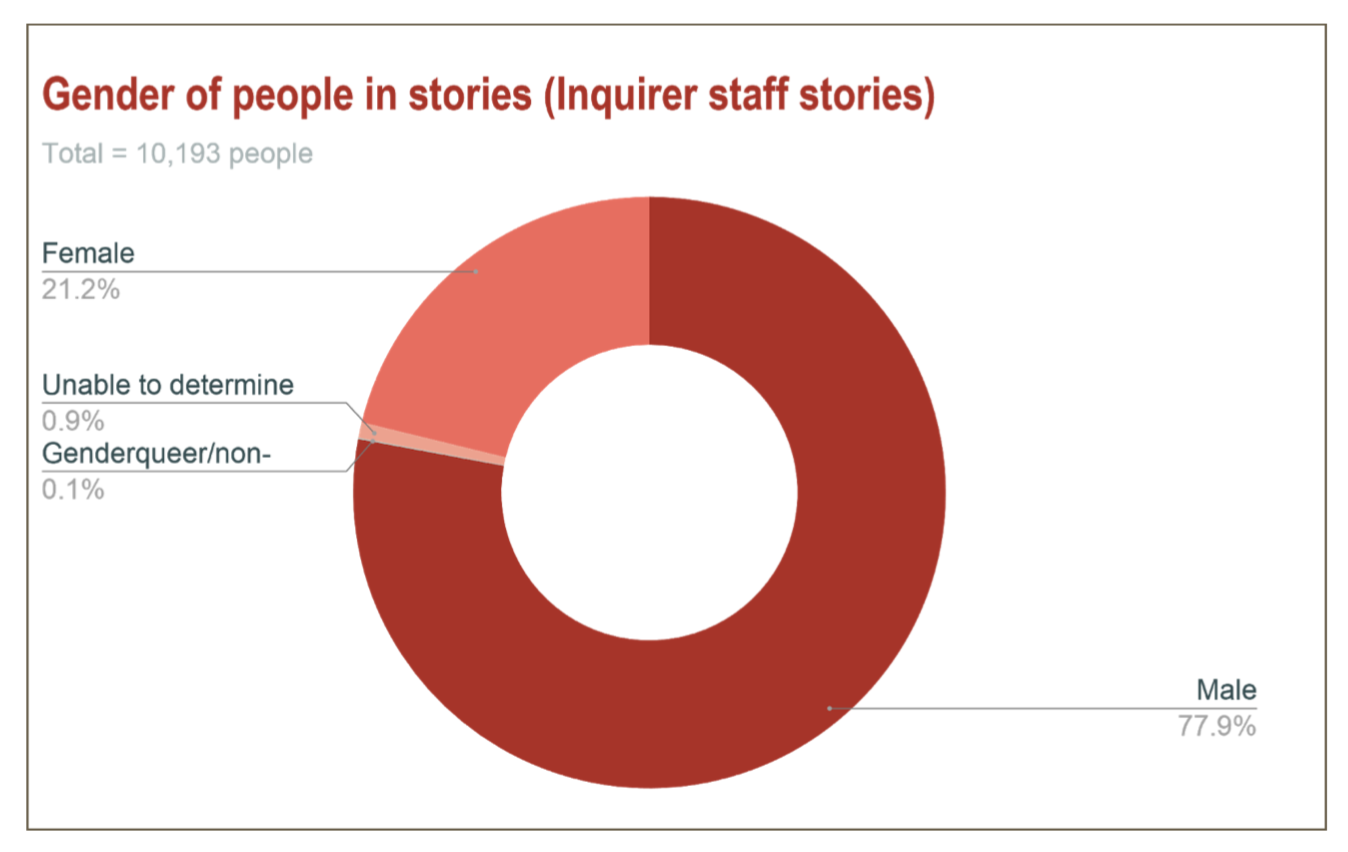

Men accounted for more than three-quarters of people featured in stories by Inquirer staff. (That 0.1% reflects that six non-binary people were represented in the Inquirer’s coverage.)

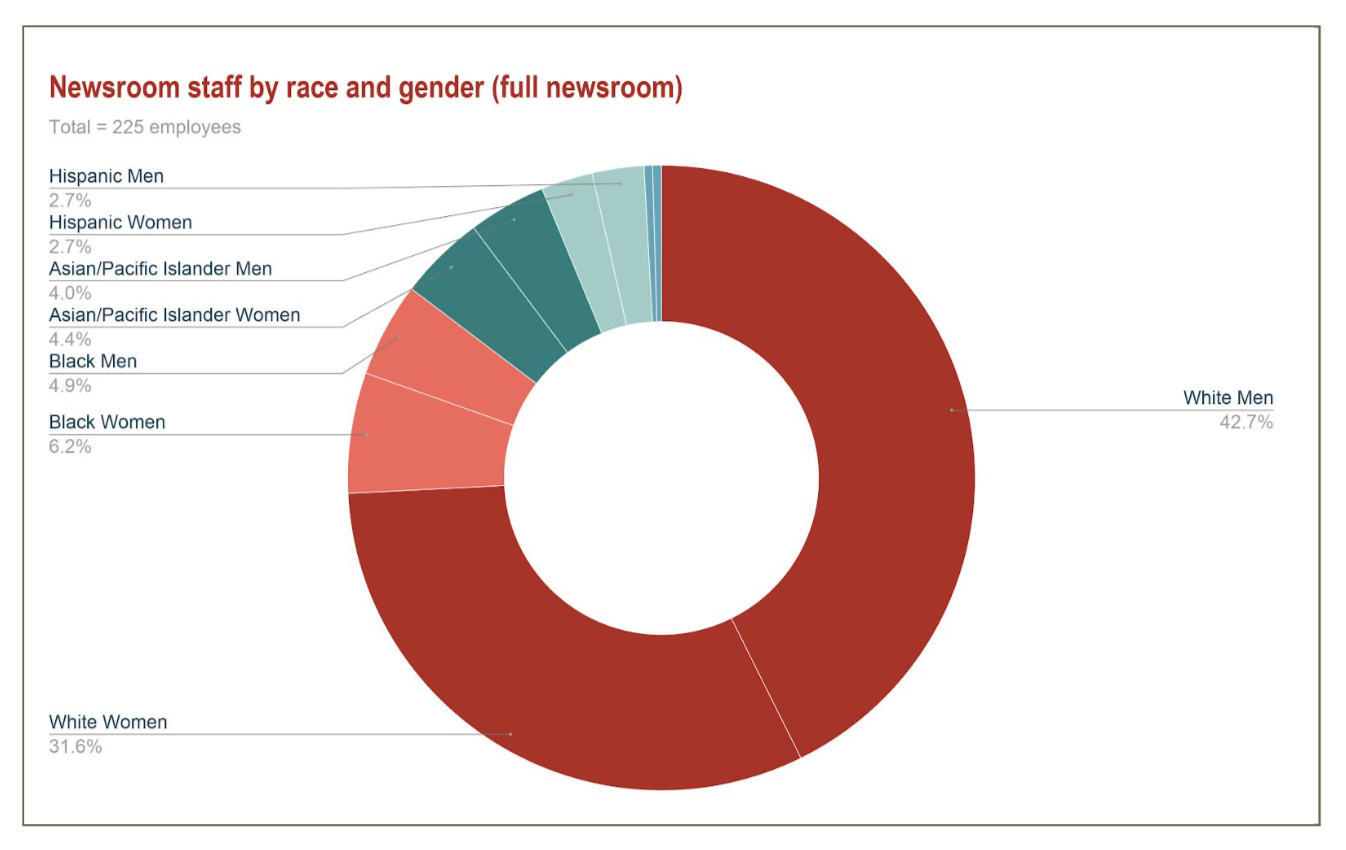

As of August 2020, the Inquirer newsroom employed 225 employees, including “management, editors, reporters, producers, photographers, news developers, coordinators” and more. The numbers show a newsroom that does not reflect the diversity of the city is covers:

The report also found that editors (77.3%) are whiter than non-editors (74.3%), and that while white (40.9%), Black (6.8%), and Asian (2.3%) women hold editor positions, zero Latina staff hold editor positions.

In a newsroom where 35 out of 47 editors are white, the report found that “allowing whiteness to remain invisible,” “assumptions about what makes a good source,” and “logistical constraints” were barriers to more diverse sourcing.

Some white editors used terms like “natural” or “organic” when describing how source diversity happened . . . Likewise, some white reporters said they focused on what they saw as the quality of sources and not their race or ethnicity: ‘My top priority is getting the best people that I can talk to on time.’

Journalists of color interviewed felt their editors had good intentions, but felt responsible for closing any gaps in understanding. “This often left them feeling trapped between expectations of reporting for communities and editors’ expectations that they were reporting about communities,” the report found.

There’s much more in the report, including department-level breakdowns. You can read the full diversity report here. You can also find coverage of its findings in The Philadelphia Inquirer.