What do people really mean when they say they do not trust the news media? And what can news organizations do to restore trust where it is deserved?

This week, our team of researchers at the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism published a new report that offers somewhat different answers than those most often focused on by journalists and other researchers (much of which we reviewed in a Trust in News Project (funded with a £3.3 million grant from the Facebook Journalism Project), a multi-year effort to better understand trust in news media, which has steadily eroded in many countries worldwide. Building on our last report and in advance of additional data collection, our team of researchers wanted to step back and listen to how people in different political environments understood the concept of trust, thought about news, and made decisions around their own media habits — including the increasingly central role played by digital platforms like Facebook and WhatsApp. In an effort to better capture these perspectives, over the past few months, we held a series of open-ended online conversations with 132 people in four countries — Brazil, India, the U.K., and the U.S.This qualitative data allowed us to better understand not only the context around how people form attitudes toward news media, but also why they take the positions they do and what kinds of characteristics are most salient when they consider the concept of trust. We highlight three of our main findings here.

First, in all four countries, we found that the line between more trusting and less trusting individuals was often blurry, even though we specifically screened participants on this basis.

People in both groups held complex and nuanced views about the variety of news sources available to them. In other words, trust in news is not a single concept but a mix of attitudes. Arguably, the more important dividing line was often between people who differentiated between news sources (trusting some but distrusting others), which helped them navigate an otherwise confusing media landscape, and those who were largely unsure about which news sources to trust (and often skeptical toward all of them as a result).

For example, some were like “Samantha,” a 33-year-old woman in the U.K. who found it “quite easy” to sort through information online because she was “quite black and white about it” and knew which brands were “entirely trustworthy.” But many others were like “Henry,” a 48-year-old man in the U.S. who relied on aggregator websites to stay informed. He said he frequently felt “overwhelmed” while trying to make sense of the news, “I’m like a hoverer where I want to know what’s going on, but I just don’t have the time to be point/counterpoint of each issue.”

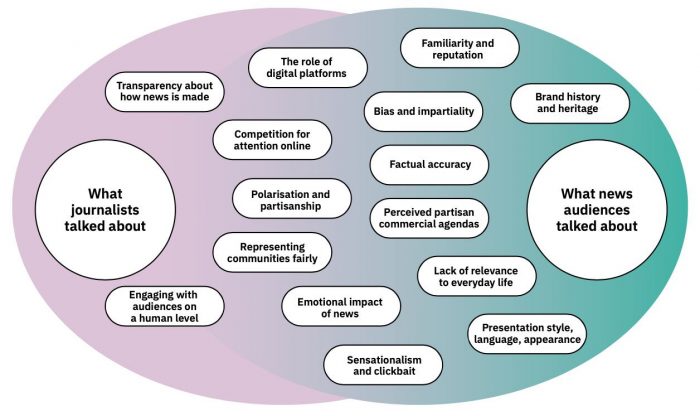

Second, while many emphasized the importance of accurate reporting (however subjectively defined) or voiced their suspicions that political or commercial agendas played a corrupting role behind the scenes in shaping news coverage, the specifics around how news organizations report and confirm information were often less at the forefront of people’s minds than gut feelings they had about brands.

Those feelings were often rooted in how familiar they were with organizations or impressions about their reputations, sometimes based on having grown up around particular news sources. As “Andrew,” a 25-year-old man we interviewed in the U.K., told us when describing how he thinks about trust, “It’s hard to put it into words because it’s very instinctual, I don’t really think about it. I just have a general feeling, really. I suppose I just trust if it comes from a major publication that I recognize.”

Many also described focusing on stylistic qualities in how news outlets presented information as an important cue for brand quality. “Pooja,” a 21-year-old woman in India, for example, said, “When I see something that has been written well grammatically and otherwise, that does lead you to trust it because you can see that the person who’s written it obviously has studied a lot, has studied the language, has a good command of the language.”

Third, social media, search engines, or messaging apps were often valued for their convenience as efficient places to find news, but many also saw digital platforms as places awash in unreliable, divisive, and even dangerous information. Where audiences did not hold strong views about sources based on their offline identities, brands were often lumped together simply by virtue of their association with the platforms.

For example, as “Lia” (43, woman, Brazil) said, “I almost never trust content coming from social media, honestly” or as “Andrea” (28, woman, India) put it, “Honestly speaking, I don’t trust WhatsApp.” Trusted brands were trusted despite appearing on these platforms with distrusted brands (and media personalities) often standing in as negative exemplars for the whole.

There are implications here for how news organizations might go about cultivating trust. It may not be enough for brands to establish trust merely on the basis of their journalism or the transparency of their methods because this may only resonate with small, highly engaged audience segments. The degree to which many people remain unaware — and even uninterested — in what makes one news source distinct from their many competitors suggests that there are opportunities for brands to better, more proactively communicate who they are, what they stand for, and how they do their work.

In crowded information ecosystems, these meta-narratives do not tell themselves. Should news organizations refrain from investing in better defining their identities on their own terms, there are plenty of opponents with vested interests who have shown they will gladly take up that mantle for them.

The full report is available here.

Benjamin Toff is a senior research fellow at the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism at the University of Oxford and an assistant professor at the University of Minnesota. Sumitra Badrinathan, Camila Mont’Alverne, and Amy Ross Arguedas are postdoctoral research fellows at the Reuters Institute.