The past year has been unusual for media consumption: With the pandemic keeping more people home, residents of Western Europe watched more TV news than usual. The growth of podcasts slowed since fewer people were out and about.

Despite changes due to Covid-19, however, the broad trends in how people get news (or don’t) continue apace, Oxford’s Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism found in its annual Digital News Report, out this week. RISJ surveyed more than 90,000 people in 46 countries about their digital news consumption. (Included in the report for the first time this year: Colombia, Peru, India, Indonesia, Thailand, and Nigeria.)

The research is based on YouGov surveys conducted in January and February of this year; the researchers also conducted focus groups and interviews in the U.S., U.K., Germany, and Brazil.

Here are some of the most interesting findings from the report:

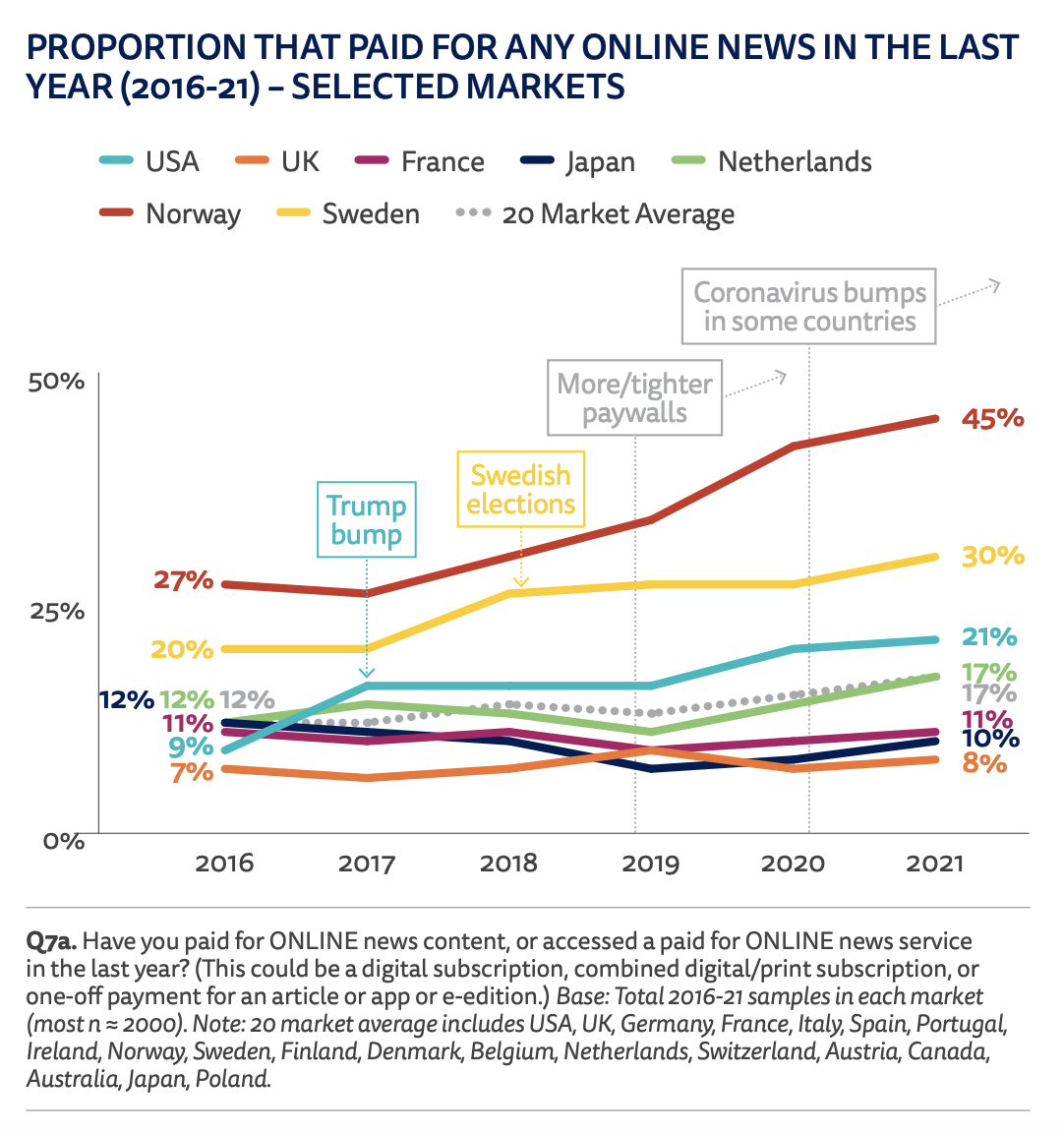

Slightly more people are paying for online news worldwide — especially, not surprisingly, in wealthy countries. And in the U.S., multiple subscriptions are becoming more common. Here, 21% of respondents said they pay for at least one online news outlet, and for those who pay up, the median number of subscriptions is two: “This means just over half of those paying take out subscriptions to more than one title.”

Across 20 countries where publishers have been actively pushing digital subscriptions, and that we have been tracking since 2016, we find 17% saying that they have paid for some kind of online news in the last year (via subscription, donation, or one-off payment). That’s up by two percentage points in the last year and up five since 2016 (12%). Despite this, it is important to note that the vast majority of consumers in these countries continue to resist paying for any online news.

We find most success in a small number of wealthy countries with a long history of high levels of print newspaper subscriptions, such as Norway 45% (+3), Sweden 30% (+3), Switzerland 17% (+4), and the Netherlands 17% (+3). Around a fifth (21%) now pay for at least one online news outlet in the United States, 20% in Finland, and 13% in Australia. By contrast, just 9% say they pay in Germany and 8% in the UK.

Large, established news organizations benefit most:

Getting on for half of all subscribers in the United States (45%) pay for one of the New York Times, Washington Post, or Wall Street Journal, according to our data. In the UK, The Times, Telegraph and Guardian account for over half (52%) of those who currently pay, while in Finland, we find that almost half of subscribers (48%) pay for just one publication, the leading broadsheet Helsingin Sanomat.

In Germany, which has long had a more competitive market with strong regional titles reaching a significant national audience, the pie is more evenly split between a range of national titles, including the tabloid Bild as well as the up-market Der Spiegel, Die Zeit, FAZ, and Süddeutsche Zeitung, while in Spain we find a mix of national titles and smaller digital-born outlets pursuing membership models.

One striking finding from our survey this year is the difference in contribution made by local and regional publications across countries. In Norway, 57% of subscribers pay for one or more local outlets in digital form. This compares with 23% in the United States, but just 3% in the United Kingdom.

“Across all markets, just a quarter (25%) prefer to start their news journeys with a website or app. Those aged 18–24 (so-called Generation Z) have an even weaker connection with websites and apps and are almost twice as likely to prefer to access news via social media, aggregators, or mobile alerts.”

As the use of smartphones for news has grown (73% of those surveyed in all countries access news from a smartphone, up from 69% in 2020), the reach of news alerts has grown too.

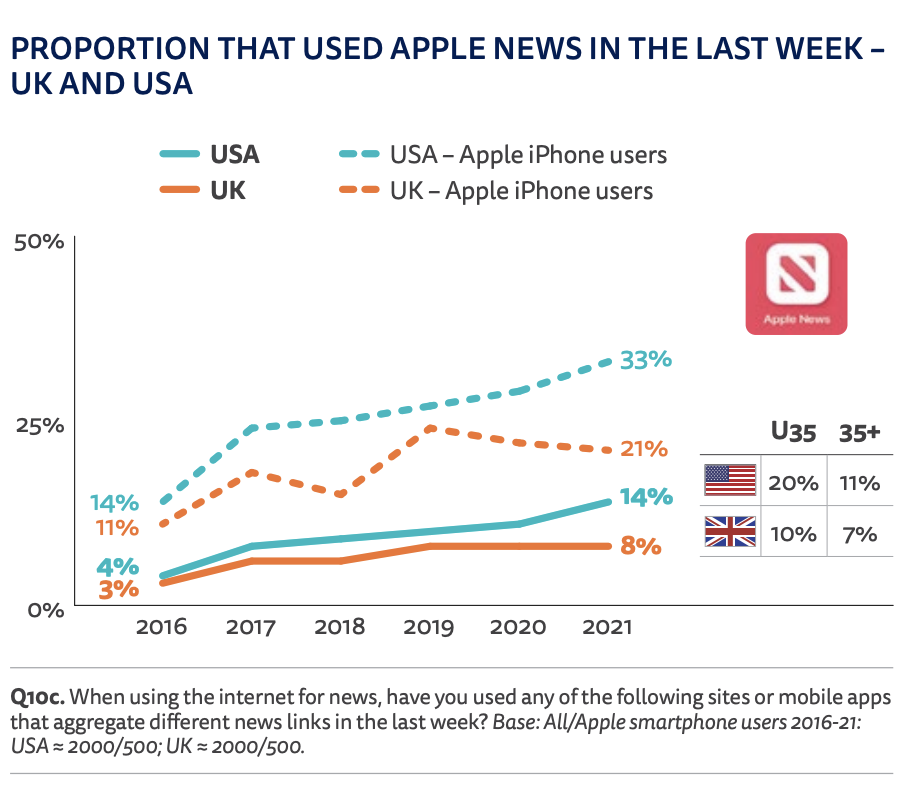

Those alerts aren’t just coming from publishers’ apps — “mobile aggregators also seem to be benefiting,” with Apple News, especially, growing in the U.S.

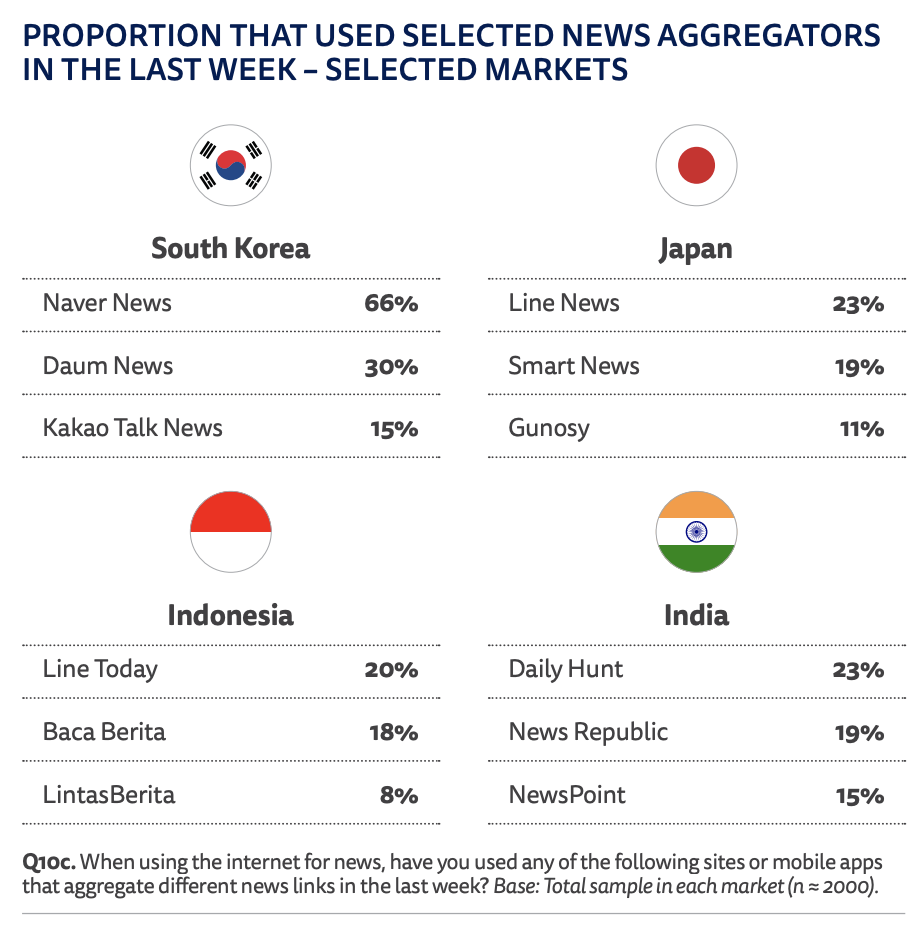

In Asian markets, different mobile aggregators have taken off, “partly due to bundling with local phone operators, partly due to the stronger penetration of Android devices, and partly because of a history of early mover advantage. But this does not fully explain regional differences. Upday comes bundled with many Samsung phones in Europe and Latin America but only reaches 8% in Brazil, 6% in Germany, and 4% in the UK.”

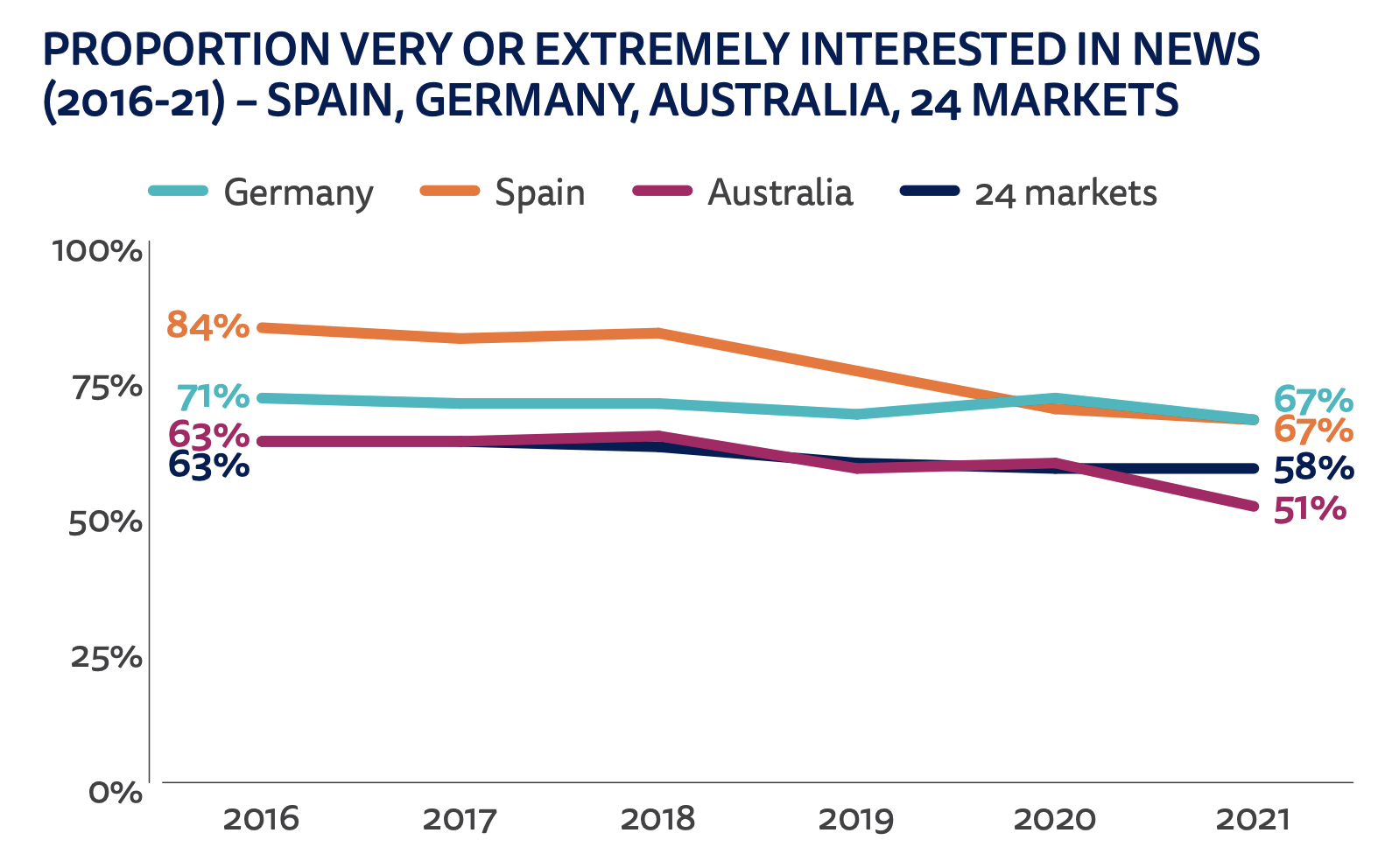

While “interest in news has risen in some countries that have been badly affected” by the pandemic, the researchers still found, overall, “a decline in news interest in a number of countries”:

The proportion that says they are very or extremely interested has fallen by an average of five percentage points since 2016 — with a 17 percentage point drop in Spain and the UK, 12 points in Italy and Australia, and eight in France and Japan. There has been little or no decline in countries such as Germany and the Netherlands.

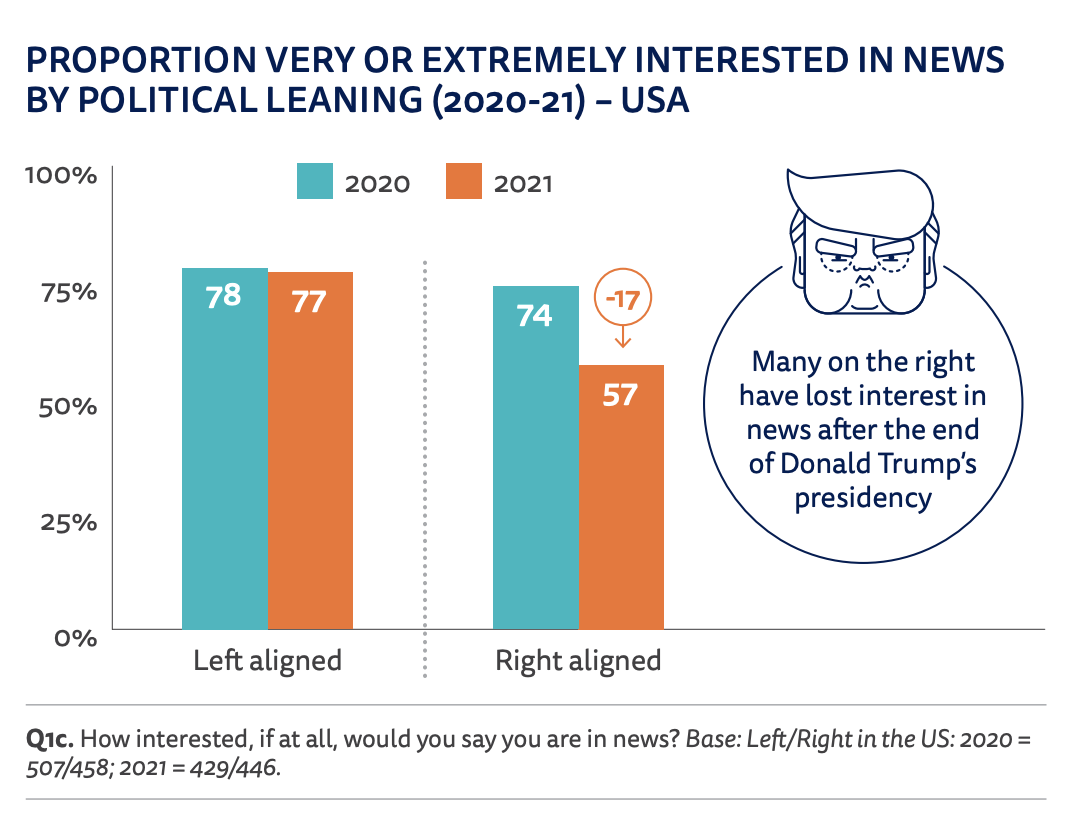

In the U.S., interest in the news (people who say they are “very or extremely interested in news”) “declined by 11 percentage points in the last year to just 55%.” That may be because Trump is no longer president: “Almost all of this fall in interest came from those on the political right.”

Across all the countries surveyed, 44% of respondents said that they “trust news overall.” That’s up from 38% last year.

In the U.S., though, trust in news in general is lower in the U.S. than in any other country that RISJ surveyed. Only 29% of U.S. respondents agreed with the statement “I think you can trust most news most of the time,” same as last year. (In Canada, the figure was 45%; in Brazil, 54%; in the U.K., 36%.)

Thus, while platforms and some, often big, publishers are doing well, many commercial news media are struggling.

Do the public know, do they find it concerning, and do they want government to step in and support?

Our data suggests that the answers are "no", "no", and "no". 7/9 pic.twitter.com/MUNGa3uGih

— Rasmus Kleis Nielsen (@rasmus_kleis) June 23, 2021

The full report, including country-specific profiles, is here.