For the March 2022 issue of Chilango — a news and culture magazine covering Mexico City, Mexico — the staff knew they had to top the year before to commemorate International Women’s Day.

“Chilango” is a term used to refer to people from the capital. As a masculine singular noun, it can also mean a man from Mexico City. “Chilangos,” as a masculine plural noun, can mean either a group of men of Mexico City or a group of people of any gender. That’s what’s called the generic masculine, where the masculine form of a word is employed when more than one gender is involved.

In 2021, the magazine changed its logo to “Chilanga” for the March edition as a way to recognize and honor the city’s women and explore issues related to feminism, motherhood, gender inequality, and femicide.

Gina Jaramillo, the editorial director of the magazine, said that conversations about feminism led to conversations about marginalization and inclusivity. So in 2022, Chilango wanted to serve people of all gender identities by adopting inclusive, nonbinary language.

Todo cambia y nosotres también. En marzo, Chilango cambia a lenguaje inclusivo no binario, un cambio y transformación en la manera de expresarnos que redefine nuestra forma de entender el mundo.

¡Conoce más del #LenguajeINB aquí! 👉 https://t.co/SpLDcZjeNy ✨ pic.twitter.com/ZLZz5gtV6V

— Chilango (@ChilangoCom) March 2, 2022

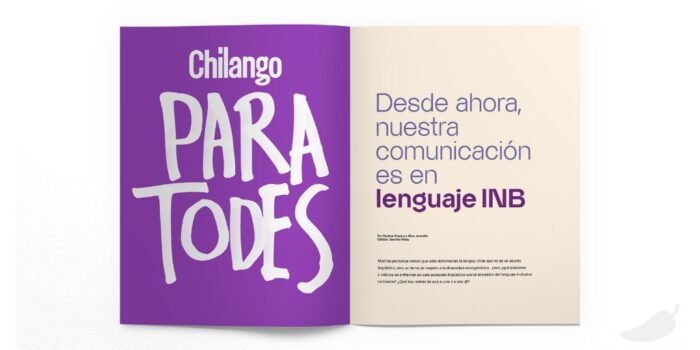

The first few pages of “Chilango para todes” debunk common misconceptions and excuses about not using gender-inclusive language and commits to using it in all of the magazine’s content going forward.

“When it comes to gender, our language has two ways of expressing it: feminine and masculine,” Jaramillo wrote in an editorial in that issue. “But far from being two fixed points, the expression of human identity offers various possibilities that deserve to be named, recognized, and that also enrich those aforementioned conversations and discussions in every way. Between ‘her’ and ‘him,’ there is a spectrum of realities that the forms of binary language fail to express. The movement for inclusive language seeks to enable these multiple existences to manifest and feel represented in the use of language.”

Adopting inclusive language proved to be a learning experience, but also an editorial and linguistic challenge for the newsroom. Jaramillo organized workshops and trainings for the staff with local experts. They put together a style guide, which serves as a practical guide but also includes Chilango’s editorial position on using inclusive language, and defines different things like nondiscriminatory language, nonsexist language, and neutral language. They started introducing it in stories prior to the March edition but made it official policy with “Chilango para todes.”

“There are situations that still elude us,” Jaramillo said. “With this manual, it definitely helped us to generate certain concepts. For example, instead of saying ‘el hombre’ [mankind], an inclusive possibility would be ‘la humanidad’ [humanity]. Instead of saying ‘los ciudadanos’ [citizens], we could use ‘la ciudadanía’ [population]. Instead of saying ‘los investigadores’ [researchers], ‘el equipo de investigación’ [research team]. Instead of ‘los empleados’ [employees], ‘el personal’ [staff].”

Jaramillo recruited Paulina Chavira, founding editor of The New York Times en Español and Mexico City’s grammar queen, to co-author the editorial and explain to readers why adopting inclusive language was necessary.

“When I’m talking to people who openly and explicitly tell me that they don’t identify with the male or female gender, it seems so basic,” Chavira said. “To the point where it seems a little illogical to explain it, but it’s about respect…Words are for expressing reality. And our reality is changing. For those of us that work in journalism, it’s a matter of our commitment to the truth.”

Chavira has always had an interest in grammar and developed the Times’ first style guide in Spanish. She’s done freelance copyediting since 2011 and has been offering grammar and editing classes since 2014. In 2017, her piece in the Times led Mexico’s Soccer Federation to add the correct accents to every player’s jersey for the first time for the 2018 World Cup.

She told me that for the last few years, she’s been talking about using inclusive language more broadly. Her interest began when she had to translate a story for NYT en Español and one of the people mentioned in the story was nonbinary. The pronoun “elle” (they) wasn’t as widely used then, and she could have skirted around it in the translation, but then decided if now wasn’t the time to learn, then when?

“We explain our reality thanks to the words we have,” she said. “Reality is there. We need to name it and we need certain structures, which are not so foreign to what we already know. It’s just a little tweaking and adjusting.”

Inclusive language has been met with resistance and ignorance in Mexican journalism, Chavira said. Lots of people, in media and society in general, argue against it because the Royal Spanish Academy, one of 23 official Spanish language institutions but the most commonly cited, doesn’t recognize it. But that hasn’t stopped people from using new words like “Omicron” or “Covid,” she pointed out. Life and language are always changing. Only dead languages stay the same.

In 2021, when pop star Demi Lovato announced that they are nonbinary, Chavira recalled that leading national news outlets in the country said Lovato used “ellos” (the plural masculine of they) and “ellas” (the plural feminine of they) as their pronouns, when both are incorrect. That showed how ill-equipped journalists were to describe reality and tell the truth with precision, she said.

En un capítulo más de «Los medios se rehúsan al cambio»:

ELLE ES DEMI LOVATO

Gracias a @apchavira por hablar del tema con toda la autoridad que le respalda como asesora lingüística y periodista ✨💜🖤💛 pic.twitter.com/T7gQIScfMs

— Láurel Miranda (@laurelyeye) May 20, 2021

With that and other examples in mind, Jaramillo was pleasantly surprised with the public’s response to the March issue. Chilango lost some followers, she said, but also gained followers and readers who understand that the future must be collective and inclusive.

“The use of non-discriminatory language can become a tool to make diversity visible,” Jaramillo said. “It can also combat stereotypes and promote a greater sense of inclusion, which is [Chilango’s] main objective. These are processes that will take us a long time, and there are going to be many opinions against us, but there will be others in our favor.”

Read the full issue here.