The U.S. midterms are tomorrow, and news outlets across the country are rolling out their voting coverage: Candidates casting their ballots, “I Voted” stickers, election workers preparing polling places, and lines of eager voters.

It’s enough to inspire civic pride — but some of these images may not be positive for democracy: Our new research, which is not yet published, shows that people who watch a television news story that depicts polling place lines are less likely to say they will vote in future elections.

Coverage of lines is prevalent, according to a content analysis we did of national and local news coverage leading up to the 2016, 2018, and 2020 elections. But, we found, seeing images of lines in news stories about voting made people more likely to think that voting is time-consuming and decreased their stated confidence in elections.

The Presidential Commission on Election Administration said in a 2014 report that no American should have to wait more than 30 minutes to vote. According to research by the MIT Election Data and Science Lab (disclosure: Christopher Mann, this post’s coauthor, is on its advisory board), the share of voters waiting more than 30 minutes to vote in person (either on Election Day or via early voting) declined from 16% in 2008 to 9% in 2016, when the average wait time was 10.4 minutes. The trend reversed in 2020, due to Covid precautions at polling places and record-breaking turnout, with the average wait time for in-person voting rising back to 2008 levels — 14.3 minutes, with 18% of voters’ waits on Election Day exceeding the PCEA recommendation.

While researchers have investigated the experience of waiting in lines to vote and the reasons for long loans at polling places, our work is the first to examine the effects of news that covers lines.

To measure the impact of news depictions of “voting lines” on the public’s attitudes about elections and voting behaviors, we conducted a series of survey experiments. In each experiment, we told participants that they would see a short video of a local news story. The television news story featured a voiceover discussing early voting details and clips depicting common voting imagery such as ballot boxes and poll workers. We created a second version of the story with one difference: It also featured clips of people waiting in polling place lines.

We then randomly assigned some participants to watch the story with lines, and another group to watch the story without the lines clips. For each story, the voiceover, which made no mention of lines, was the same. After watching the stories, all participants answered questions about their intention to vote and their confidence in elections. We also asked them to estimate what wait times would be at their local polling places and nationally.

We fielded each experiment on a nationally representative sample of Americans ages 18 and older, recruited by Lucid to complete an online survey. The first experiment was conducted in January 2021, around the Georgia run-off, with 1,729 participants. The second experiment took place last week, among 2,559 new respondents, to verify the results in the electoral context in which people will encounter these stories.

(For the sake of comparability, we’re focusing in this post on the two experiments that used video. We also conducted a third experiment that used a print news story with an image of either a polling place line or of people casting their ballots. Our results were consistent across the TV and print news experiments, which suggests these effects are not specific to television news.)

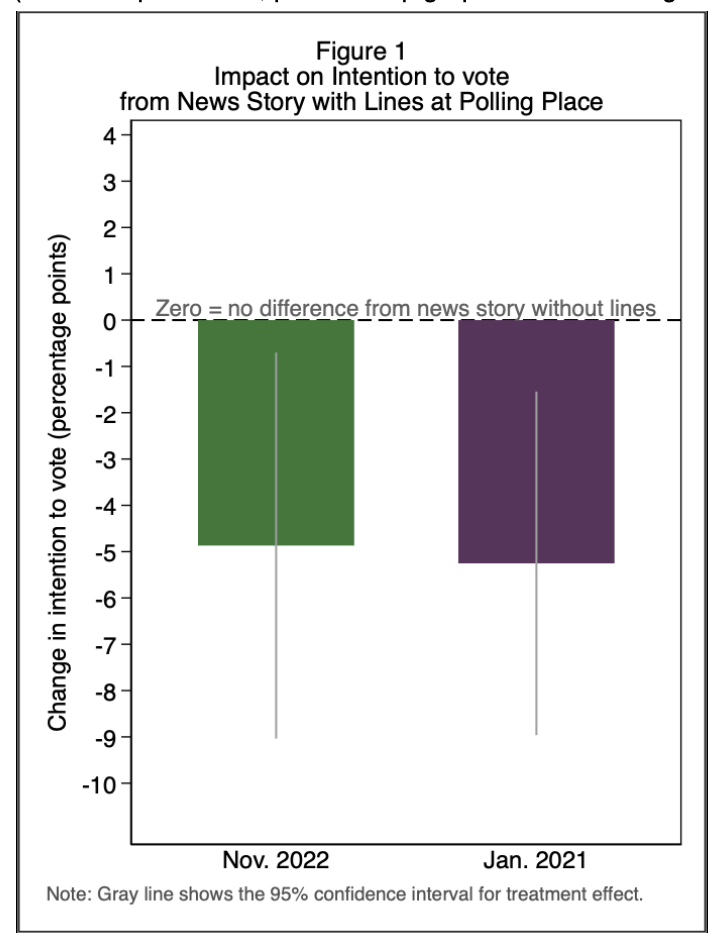

Our finding: Americans who see news coverage that shows generic “line” images at polling places are significantly less likely to say they will vote in future elections. In our most recent experiment about midterm elections, 54% of people who saw the TV coverage that showed lines said they “definitely” planned to vote, while 59% of people who saw the TV coverage without lines said they “definitely” planned to vote. Our January 2021 experiment produced a similar 5 percentage point decrease in vote intention when people saw TV coverage showing lines compared to TV coverage without lines (64% vs 69%).

Our finding: Americans who see news coverage that shows generic “line” images at polling places are significantly less likely to say they will vote in future elections. In our most recent experiment about midterm elections, 54% of people who saw the TV coverage that showed lines said they “definitely” planned to vote, while 59% of people who saw the TV coverage without lines said they “definitely” planned to vote. Our January 2021 experiment produced a similar 5 percentage point decrease in vote intention when people saw TV coverage showing lines compared to TV coverage without lines (64% vs 69%).

Seeing news about lines to vote also appears to have negative impacts on elections beyond the polling place. After seeing stories about polling place lines, the share of respondents who reported that elections were “well run” dropped by 6 percentage points in November 2022 and 5 percentage points in January 2021.

Seeing news about lines to vote also appears to have negative impacts on elections beyond the polling place. After seeing stories about polling place lines, the share of respondents who reported that elections were “well run” dropped by 6 percentage points in November 2022 and 5 percentage points in January 2021.

Consistent with prior research, our experiments also shed light on why news stories about lines decrease turnout: They lead viewers to perceive voting as time-consuming. Seeing a story about lines at polling places increased the share of people who expected wait times longer than 30 minutes in their community by 14 percentage points in November 2022 and by 11 percentage points in January 2021 — with many of these people expecting waits longer than two hours.

Consistent with prior research, our experiments also shed light on why news stories about lines decrease turnout: They lead viewers to perceive voting as time-consuming. Seeing a story about lines at polling places increased the share of people who expected wait times longer than 30 minutes in their community by 14 percentage points in November 2022 and by 11 percentage points in January 2021 — with many of these people expecting waits longer than two hours.

Our findings suggest that journalists’ choices to feature images of lines in Election Day coverage can have real effects on voting.

Some caveats are in order. We didn’t follow up on whether people actually did vote, or whether their attitudes toward wait times and elections persisted. It is unlikely that one news story featuring images of lines is enough to cause lasting behavioral and attitudinal change. It is also possible that news audiences, rather than the public writ large, are politically interested enough and have enough knowledge of elections to deter any effects of such line coverage.

Still, our results are persistent across electoral contexts and types of coverage (television and print). They are also significant despite a relatively “weak” treatment of only varying the inclusion or absence of line images.

These results yield some practical recommendations that are relatively easy for newsrooms to implement.

First, journalists should ask themselves if “lines” are a crucial part of the story. If they aren’t, other images might work better.

If voting lines are important to the story, it’s useful to provide more context. Journalists can check to see if wait times are longer than the 30-minute maximum recommended by the Presidential Commission on Election Administration, and can also check whether wait times are consistent throughout the day. A study by the Bipartisan Policy Center and MIT Election Data and Science Lab, observing 4,229 precincts in 88 jurisdictions across 11 states, showed that the longest wait times of the day occur in the early hours when a polling place first opens, and usually decline once polls are open.

When wait times are significant, more detail is important. Are the lines indicative of a meaningful election administration failure? Are they due to high turnout? Context about reasons for a wait will help voters hold election officials accountable when there is a genuine problem. But generic images of polling place lines shouldn’t be used thoughtlessly — because they may dissuade people from voting and reduce their confidence in elections.

Kathleen Searles is the Sheldon Beychok Distinguished Associate Professor of Political Communication and holds a joint appointment in the Manship School of Mass Communication and the Department of Political Science at Louisiana State University. Christopher Mann is an associate professor of political science at Skidmore College and a member of the advisory board for the MIT Election Data and Science Lab.