There is lots of excellent work being done these days to support nonprofit journalism, from building networks and collaborations to offering shared resources to assembling benchmark data and market research to individualized coaching. Yet this week I come not to praise these efforts but to worry about whether they may be getting a bit out of scale to what I see as the even more pressing need for funding nonprofit news organizations directly.

I am increasingly worried when I observe what I see as the increasing fragility of many nonprofit newsrooms juxtaposed with the robust growth of the intermediaries whose mission is to support them.

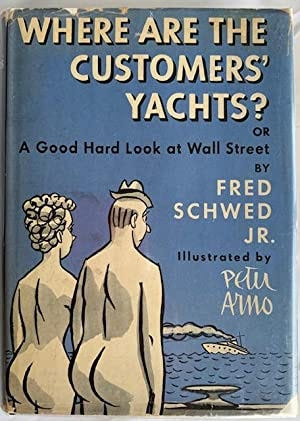

In 1955, an observer of finance wrote a book with the subtitle “A Good Hard Look at Wall Street.” The title derived from the reply of a visitor to New York who was told to look out to the harbor at all the fancy boats owned by bankers and brokers. It was called Where Are the Customers’ Yachts? It is a question we should metaphorically be asking ourselves in the emerging digital news ecosystem.

In 1955, an observer of finance wrote a book with the subtitle “A Good Hard Look at Wall Street.” The title derived from the reply of a visitor to New York who was told to look out to the harbor at all the fancy boats owned by bankers and brokers. It was called Where Are the Customers’ Yachts? It is a question we should metaphorically be asking ourselves in the emerging digital news ecosystem.

Here are a few facts that make me worry:

Let me be clear: a great deal of good work has been and will be done with such money by these and other fast-growing intermediaries, including the News Revenue Hub, Media Impact Funders, the Solutions Journalism Network, and many others.

But I wonder if more good might have been done by directing much of institutional foundations’ money instead to the most deserving news nonprofits — both those with proven track records of excellence and convincing plans for the future AND those with exciting ideas, innovative models and promising leadership.1

I would argue, however, that making these choices, no matter how difficult, is precisely what institutional foundation staff is paid to do. The Knight Foundation, for instance, spent more than $10 million on staff and trustees in 2020 in order to make $71 million in grants. The much larger and more diversified Ford Foundation spent on staff and trustees in the same year about as much as Knight spent on grantees ($71 million again) to make about $805 million in grants. I don’t necessarily have a problem with this. Having assembled an expert staff of capable people, however, hard choices should not only be possible, they should be required. Experts should not outsource the heart of their own work.

In fact, I would have no problem with foundations increasing program staff a bit if they think that’s required to make the necessary choices at the appropriate scale. It would surely be more efficient than subsidizing an ever-expanding web of intermediaries, remembering that every time water is poured out of the philanthropic bucket, some of it necessarily leaks.

The metaphor that worries me most on this topic is not actually Wall Street capital and missing yachts. It’s organized labor and lost jobs. In the last third of the last century, the proportion of the workforce that was unionized fell by more than half, as good jobs disappeared by the millions, spurring a significant part of the alienation that is tearing this country apart even now. At the same time, top union leadership at places like the AFL-CIO held comfortable sinecures, hobnobbed in Washington, and convened comfortably in Florida. A visitor looking to Bar Harbour might have asked, “Where are the rank and file’s jobs?” Too few asked that question until it was too late. I hope we can avoid that mistake in the news business.

Richard Tofel was founding general manager (and first employee) of ProPublica, and was its president from 2013 until January 2022. This post originally appeared on Second Rough Draft, his newsletter about journalism — subscribe here.