There are many reasons to track your newsroom’s sources, and many ways to do so. At KQED, creating our own source tracker allowed us to discuss newsroom priorities, involve hesitant staff, and hold ourselves accountable for who we feature in our stories.

When journalists talk about source tracking and the challenges of culture change in a newsroom to embrace this key task, we often focus on buy-in and accountability. What can sometimes be lost is the nitty-gritty of how, what demographic data we’re collecting, and why.

When it comes to collecting demographic data, there’s no shortage of information a reporter can ask of their source: age, gender, profession, location and more. The list can be expansive, and when a journalist is on a tight deadline — and concerned about burdening a source who’s already answered several questions about a subject — it’s important to develop a questionnaire that works for your newsroom staff, while meeting the goals of the organization.

KQED is the largest public media organization in California and has one of the largest newsrooms in Northern California. In our coverage we strive to identify structural inequities and are aware of how we in the media might replicate those injustices by relying on the same sources over and over in our news coverage. There are several ways to improve our coverage through staffing and story framing, but we can also try to address inequities by being conscientious about who we feature in our coverage over a period of time. This is why we co-created a source tracking questionnaire with our staff.

Below we explain how we developed our questionnaire, how a lack of participation among staff created problems in mapping an accurate snapshot, and how we developed solutions to address compliance. We also examine the responsibility managers have in implementing change in the newsroom.

The one-time 2020 source audit allowed us to establish a baseline. We outsourced that work to Impact Architects, which specializes in source audits for newsrooms. You can read the results here.

However, we did not have a dedicated budget to continue that third-party work. We needed — and wanted — our journalists to take over the responsibility of tracking sources in KQED News’s stories.

We had reviewed several source-tracking questionnaires, but every newsroom is different. We tried to create a questionnaire that aligned with the retrospective results to track year-over-year information on race, gender, location, and profession. However, once we started testing that questionnaire with staff, we received a ton of questions, and that presented an opportunity: We needed to create our own form.

Guided by KQED News department’s editorial North Star and our focus on systems, solutions, and equity, we wanted to create a questionnaire that worked for our culture and aligned with reporters’ busy schedules.

In order to create a questionnaire, first, you need a team. It’s easy to think of tasks as single-person assignments because you don’t want to tie up more resources. However, working in teams is critical for stress-testing assumptions and creating support systems in times of challenging work.

Team roles. We settled on three roles: Data specialist, facilitator, and enforcer. In newsrooms across the country, data journalists have played a significant role in source tracking work by providing guidance on tools and data sets and, often, cleaning the source data and creating reports for internal staff. Data specialists play a critical role in making the source tracking data achievable and manageable. Facilitators can guide staff through difficult conversations and help groups make choices. Enforcers are the ones in top management ranks with the power to tell staff that a new initiative is now a job requirement. These three roles work together because you don’t want to enforce an inadequate tool, nor do you want a great tool without proper enforcement. And neither is very useful without staff buy-in. (You’ll note this article is authored by three people — these were our roles.)

Staff participation. When the team received pushback from staff over the initial questionnaire, we decided to change tactics by including staff in developing the next version of the form. Who else would be better qualified to create the questions than the people who would be asking them? In March 2021, we embarked on a series of five meetings to make the form work. Each newsroom team associated with a beat, program, or platform was required to appoint one representative who would then become the go-to expert on their team for any questions about the form. We had more than a dozen representatives.

Asynchronous participation. We made all discussions asynchronous and accessible by working on Slack and making meeting notes always available on a Google doc; these two tools helped mitigate bottlenecks. For example, if a reporter has a question on Slack about how to classify a source, you now have at least a dozen colleagues who can help answer that question. Not everyone works 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. in a newsroom and we wanted people to have opportunities to participate regardless of whether staff work on weekend teams, time-shifted, or have caregiving responsibilities.

Another large benefit of asynchronous participation is that your working documents become a searchable record. This creates transparency about how decisions were made. Also, it allows people to find previous decisions, making your Slack or Google document a living FAQ.

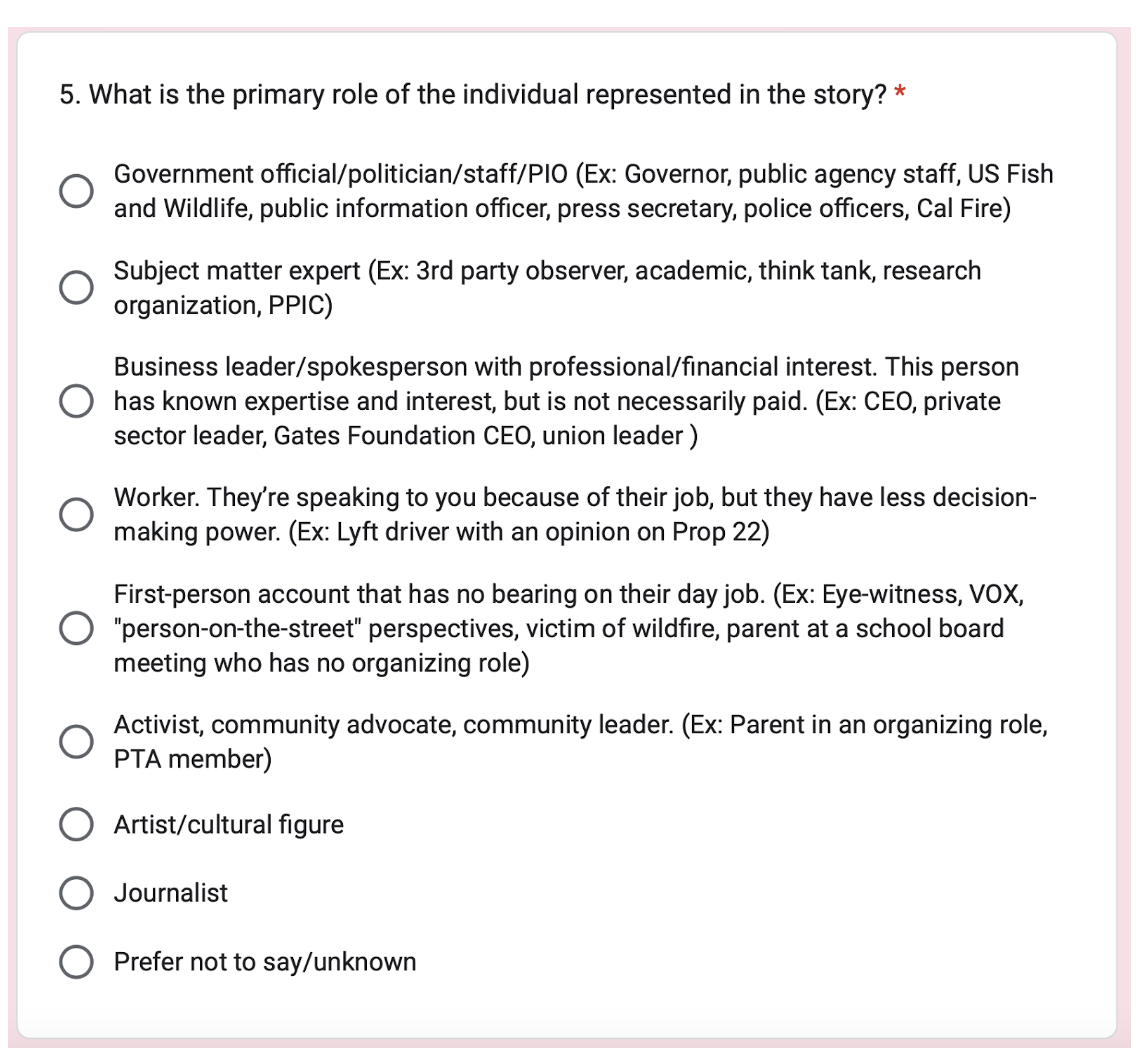

Conversation. We made time to have deep discussions. We developed our form over five weeks during weekly one-hour meetings with clear ways for people to participate asynchronously. In between those meetings, our representatives solicited feedback from their individual teams. For example, our colleagues felt dissatisfied with using job titles for sources. Several source-tracking projects identify individuals based on their jobs: professor, business person, lawyer. But people in those jobs have varying degrees of power in society, and how they are represented in a story does not automatically reflect the job they have. One can be a professor, but be in a news story as a worker striking for better pay. One can have a business interest without being paid for that work. One can be a lawyer, but speak as a first-person witness to a wildfire. This is where we decided to classify people into the roles they serve in the story and identify what structural power they hold.

Compromise. We had to make the form work, both for the daily workflow of journalists and for the larger goals of the data specialist. Journalists, in their commitment to accuracy, did not like the broad racial and ethnic categorizations that would miss someone’s deep heritage. However, in order to see trends and to have some consistency with existing data sets (such as the Census) and to have a baseline for comparison with our communities, we used the broader racial categories used by the Census and other federal agencies. There is a notes section that reporters can use for anything that is not reported in the broad categories.

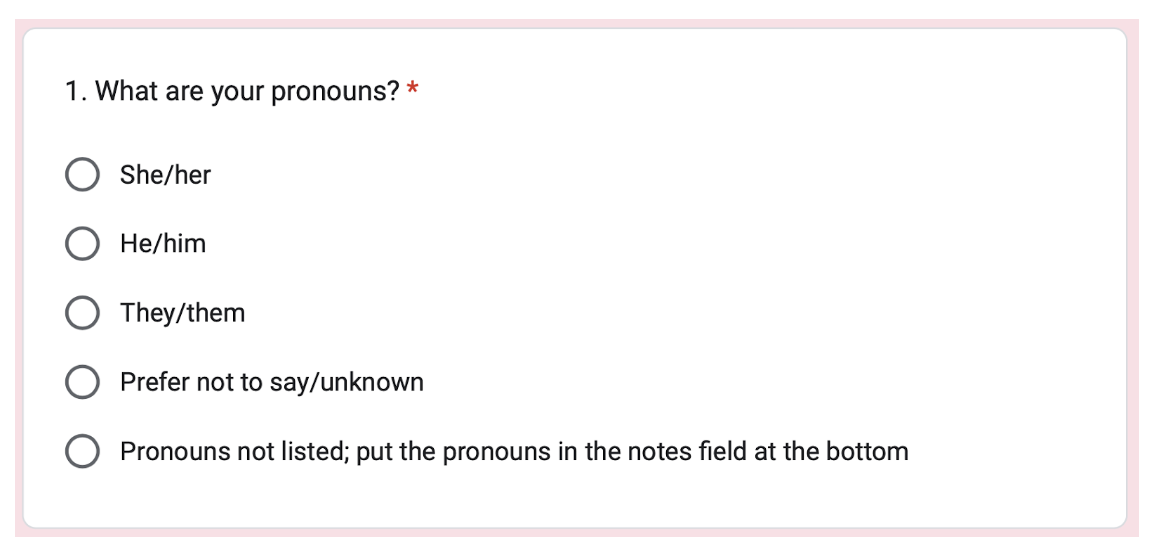

Our colleagues became the best stress testers of this process. For example, in an earlier version of the questionnaire on gender pronouns, we had “other” as a response for someone whose gender pronouns were not listed. Correspondent-producer Suzie Racho tested the form with a guest who informed her that “other” felt like it was marginalizing that person’s gender pronoun, so we updated the form to say “Pronouns not listed; put the pronouns in the notes field at the bottom.” In order to align the information with what a reporter would find useful for their story, we chose pronouns instead of sex.

Workflow. Ultimately, it’s up to our colleagues to develop a workflow, which is why we had a representative from every team to help facilitate the process. Each team is unique. For instance, who should fill out the source questionnaire for a daily talk show — the host who speaks to the source or the producer who books them? What happens to sources that don’t make it into the published story? What about breaking news situations? Having our full staff represented allowed each team to come up with its own workflow. Some teams fill out the form every Friday, some people do it at the end of the month, and others as their stories air or publish. The workflow is different for each team, and reporters learned about one another’s differences on Slack as questions and comments rolled in and were answered by about a dozen qualified representatives.

Once we had this staff-developed form, the newsroom felt confident in launching the source tracking form.

For anyone who’s been through this process, we assume they will have heard the same two most asked and answered questions:

Q: Is this mandatory?

A: Yes.

Q: Can I email my source this form?

A: No.

We wanted our reporters to have conversations and ask sources directly to collect the answers, and we knew that emailing the form to sources would remove that 1:1 interaction. The entire purpose of the questionnaire is to have the conversation about race, gender, and identity, which we know even more clearly is at the root of system inequities. We felt good about having a path forward.

As with many new initiatives, the first month was rocky. Not everyone was filling out the form. But gradually, more and more people started completing the forms. And then, participation began to wane.

Were journalists not talking to a lot of sources or were they not completing their source tracking forms? Both were problematic.

Even though the mandatory nature of the source tracking was communicated repeatedly over email, Slack, and Zoom meetings, the participation was lackluster. When comparing Phase 2 completed forms to the sample of stories Impact Architects analyzed in 2020, we realized our staff was lagging far behind where they should be. Staff had been told repeatedly that the form was mandatory. What went wrong?

We turned to our managers for answers. Our editors are the ones who know their content best. They have the best idea of how many sources their direct reports are speaking with every month. They are most in tune with how many sources appear on a program, segment or platform each month. This is where it’s important to have an enforcer, at the highest level of management, deeply involved with source tracking.

Our news director and facilitator spent several months’ worth of meetings working with editors to come up with a base number of sources interviewed each month by members of their team. This became the “Denominator Project,” which helped us understand whether staff were completing source tracking forms.

This fact-finding mission also helped clarify use of the form and helped us to, again, tackle those commonly asked questions. By the end of September 2021, managers were able to unearth gaps in completion, answer questions about whose responsibility it is to complete the form, and get more clarity on who should be involved in a source form.

The Denominator Project helped teams set targets and know whether their staff were completing their forms. It allowed us to establish a baseline that senior editors were well-positioned to determine once they had some data and deliverables.

With a baseline in place developed by editors, KQED News reset its course last October to get more accurate source tracking.

For example, our supervising senior editor of news and newscasts, Ted Goldberg, determined that approximately 200 sources appear in one month’s worth of weekday newscasts. He can look at the source tracking data and can get a better idea of whether his team is completing them or not. It’s worth noting that during Phase 2, newscasts outperformed all other programs in source tracking completion with at least 100 sources each month, some of it attributed to the sheer volume of newscasts that are produced every day. However, the Denominator Project revealed that the number is closer to 200 sources. Through constant vigilance and making source tracking a part of the daily work conversation, the newscast team maintained its 200-plus sources every month throughout the spring. Once we do a thorough analysis of the sources, we’ll know how the entire newsroom fared in getting an accurate count of its sources.

We still have a lot of work ahead of us. Tracking our sources is just one of many parts needed to have a more equitable newsroom. But by identifying our shortcomings and creating pathways for improvement, we can continually do better to better serve our audiences.

Ki Sung (the facilitator) is managing editor of digital news at KQED. Lisa Pickoff-White (the data specialist) is a data journalist at KQED, working with Stanford University and the California Reporting Project. Vinnee Tong (the enforcer) is a JSK journalism fellow at Stanford University on temporary leave as KQED’s news director.