There are lots of problems with the traditional business models of news organizations, but one of the biggest is the emergence of search advertising. This is the way Google makes most of its money ($21.1 billion in ’08): the idea that an ad that is generated by someone’s search terms can be far more targeted — and thus far more valuable — than a display ad in a newspaper or a banner ad on a web site.

If you sell giant purple bowling balls and you can advertise only to people searching Google for “giant purple bowling balls,” that’s a much more efficient exchange than what traditional media have been able to offer. (Like, say, a tiny ad in the sports section next to the box-score agate, or a classified ad lost in a sea of type, or a 30-second spot shown to tens of thousands of people with no interest in bowling balls of any size or hue.)

And typically, the advertiser only pays if the user actually clicks on the ad — not just if she sees it. This is why Google has come to dominate so much of the online advertising market: They have the most searchers, so they can serve the most search ads.

While I’ve known about search ads for years, I’ve never actually bought any as an advertiser. Since I now have a web site to promote (this here one), I decided to go through the Google AdWords experience and report how it went.

Anyone with a Google Account and a few bucks can do it. It’s a streamlined process; after all, the pages that allow for the automated sale of search terms are probably the most valuable turf Google has outside its front door and search-result pages. The heart of the process is the selection of the keywords you want to cause Google to present your ad to the user. Different keywords cost different amounts of money, depending on how much demand there is from other advertisers for those keywords. (Traditionally some of the highest cost-per-click ads have been for searches involving mesothelioma, because people with the disease often have a good lawsuit against their former workplaces, and lawyers are happy to pay big money to reach them.)

So I had to decide what searches I wanted to generate an ad for the Nieman Journalism Lab. Here’s what I settled on:

— “future of newspapers,” “future of journalism,” and “future of news.” I figured anyone searching for those terms would be almost precisely our target audience.

— “journalism careers” and “journalism jobs.” We don’t post job listings or anything like that, but I figured (a) lots of people are probably looking for jobs right now, and (b) what we write about would be useful to someone trying to navigate a career in journalism these days.

And then a few odd ones:

— “jeff jarvis” and “jay rosen.” Jeff and Jay are two of the titans of the future-of-journalism biz, so I figured anyone searching for them would probably be up our alley. Plus, Jeff’s got a book out right now, so I thought there might be room to piggyback on his traffic.

— “crowdsourcing” and “online advertising.” Crowdsourcing because it’s a topic we have a lot of content about — it was the subject of our first Book Club — and online advertising because I wanted to see what kind of results we’d get for a very broad keyword that attracts megahits.

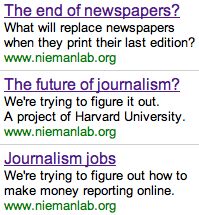

And for those keywords, I created three different ads (left). As you can see, one pushes the straight “journalism jobs” angle; the other two are questions. One of the subheads is a question; one mentions the Big H; and two have an aspirational “we’re trying to figure this stuff out” tone.

And for those keywords, I created three different ads (left). As you can see, one pushes the straight “journalism jobs” angle; the other two are questions. One of the subheads is a question; one mentions the Big H; and two have an aspirational “we’re trying to figure this stuff out” tone.

So what did we learn? After one week of advertising, here were our results:

— There wasn’t any noticeable difference between the three ads in terms of effectiveness. The one that mentioned Harvard had a marginally higher clickthrough rate than the others (0.07 percent rather than 0.05 for the other two), but that’s just noise in the data.

— One of the search terms — “future of newspapers” — was much more effective than the others at generating clicks. Its clickthrough rate was 4.53 percent; “future of journalism” was next with 1.15 percent, with everything else below one percent. Again, we’re dealing with small numbers here, but the gap between “future of newspapers” and everything else looks real.

— Clickthrough rates were much higher on Google searches than on other sites. When you buy keywords from Google, those keywords might be drawn from search terms — or they might be drawn from the context of any web page around the Internet that has Google AdSense on it. (You can choose to serve your ads only to searchers and ignore the AdSense sites if you like.)

Our ads that appeared on Google search results pages generated 25 clickthroughs out of 6,618 impressions — about 1 in 265. Those on other pages in the “content network” generated only 17 clicks from 61,170 impressions — about 1 in 3,600.

— The largest number of impressions, by far, were for the keywords “journalism jobs” — more than five times the number for any other search term. Which shows, I suppose, that lots of journalists are looking for work.

— My more unusual keywords didn’t bear much fruit. Jay and Jeff generated only one clickthrough between them out of 870 impressions (and sorry, Jeff, it was for Jay). Crowdsourcing was a complete bust. Online advertising did a little better: 2 for 283.

So was it all worth it? The final result was that, for $26.59, 42 people came to our web site. That’s 63 cents a person, and six people a day. We don’t sell anything here (not even our audience’s attention), so in some sense AdWords isn’t meant for folks like us.

But I can think of a number of things I could do to generate more than six clicks a day. A few good tweets on Twitter promoting one of our posts would generate far more than that. So would sending an email to a blogger who might be interested in something we wrote. So would posting something on Digg or Reddit or StumbleUpon, or putting a link in a Facebook status update. So would leaving a useful comment on someone else’s blog.

That’s not to denigrate the usefulness of advertising — a Google ad can help you reach someone who has no idea they’re looking for what you have to offer, and it doesn’t rely on the incestuous world of fellow Twitterers/Facebookers/bloggers.

But my instinct is that, for most of the news startups out there, social media is going to prove a more useful tool than buying ads. And, more importantly, using social media encourages all sorts of good behavior that’s critical to any online news organization — listening to your audience, integrating yourself into an online ecosystem, and understanding how your readers find news and information.

Twenty-six bucks ain’t much, but — even considering the time investment social media can require — zero is even better.