Absent the glamour of the black mock turtleneck, Apple’s Thursday event, held at the Guggenheim Museum in New York, still came bearing flowers of rhetoric, lovingly transplanted from their native soil in Cupertino’s sunny clime. One such rhetorical staple, the feature checklist, made its appearance about nine minutes in. Usually, the checklist is used to contrast Apple’s latest magical object with the feature set of lesser smartphones or other misbegotten tech tchotchkes; it was more than a little eye-popping to see the same rhetoric of invidious comparison used against the book in full — that gadget which, as senior VP Phil Schiller reminded us, was invented (in its print incarnation) back at the end of the Hundred Years’ War.

As Schiller ticked down the list, for feature after feature — portability, durability, interactivity, searchability, and currency — the book earned a big red X. Curiously, Schiller didn’t let his earlier observation of the antiquity of books undermine his critique on the grounds of their durability; not only the technology of the book, but many actual tomes survive from Gutenberg’s era; and when older formats are taken into account, far older books are still with us. It is comparatively difficult to imagine an iPad of today, much less an app designed to run on one, still in use two hundred, five hundred, a thousand years hence.

In a more focused sense, Apple’s critique of the textbook is valid. But the problem with textbooks isn’t that they’re books per se; it’s that they’re overdetermined, baroque in their complexity and ornamentation.

Modern textbooks are monsters — heavy, unwieldy, battened on siloed content. They’re like ’90s-era computers, loaded with bloatware that blunts their processor speed and complicates their interfaces. Already, today’s textbooks rarely come as paper-only devices, but include (for significant extra licensing fees) websites, online editions, networked assessments, and interactive assignments. For the wired child, these electronic ancillaries solve the portability problem; for the less prosperous or fortunate pupil, the backpack is still very heavy.

The major education publishers have become massively efficient inhalers of content, capturing licenses for images and objects held in museums around the globe, hiring phalanxes of MAs and ABDs to craft mazes of matrices, rubrics, and quizzes, and deploying batteries of sales reps to market-test every page, every image, every checklist. It’s a prosperous model — and as Tim Carmody evocatively documented at Wired yesterday, this prosperity has enabled education publishers to leverage their way into trade publishing and other media. It’s no wonder Apple is taking aim at them.

The iPad is an extraordinary device, but it’s hardly the first avenue multimedia has taken to the classroom. The filmstrips and 16mm movies of my childhood could be engaging experiences too — and they could be time-fillers for addled, overstretched teachers as well. Schiller made a sentimental play to this constituency, opening his presentation with a series of excerpted interviews in which teachers sang the sad litany of challenges they face: cratering budgets, overcrowded classrooms, unprepared, disengaged students. The argument that Apple — founded by dropouts and autodidacts — is fundamentally motivated to change this set of conditions is as ludicrous as the notion that the company could ever hope actually to do any such thing.

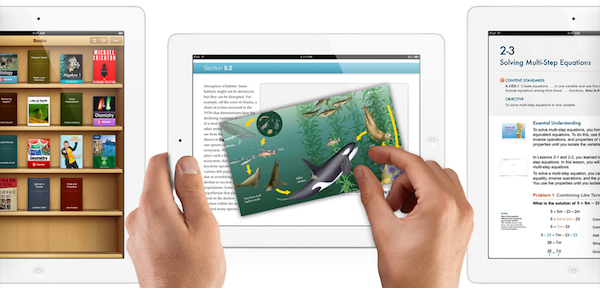

The textbooks demonstrated in yesterday’s event were lovely and compelling — and they looked strikingly like current textbooks. Roger Rosner, who heads productivity software for Apple, gave a tour of Life on Earth, a title created in conjunction with E. O. Wilson’s Encyclopedia of Life project; after playing the book’s cinematic introductory sequence, he swiped through pages featuring familiar modalities of intertextual braiding and layering: things like tables, block capitals, and callout boxes, which derive from mid-20th-century rotogravure magazine production — only sprinkled with videos, animations, and interactive images, in Apple-controlled formats, subject to development cycles originating in Cupertino (and routed through Shenzhen). At one point, he dove into a microphotograph of a cell to pop out a rendering of a strand of DNA. The helix shimmered invitingly, but disclosed none of its secrets.

Here’s the thing: Interactivity doesn’t exist. More properly, everything is interactive. We use the catch-all term “interactivity” to brand as novel the qualities exhibited by digital objects striving to be like real-world objects. But chairs, raindrops, sandwiches, and envelopes are also interactive — in their own evolved ways. Books in fact exhibit rich interactive habits, evolved to engage us in peculiar ways (and increasingly, these very features are counted as bugs).

Digital objects, too, evolve their own ways of reaching out to meet us halfway. The spell of the real makes us strive for a specious virtuality, to try fashioning uncanny appendages for objects that live in databases and go to work in networks. Tellingly, it’s at those uncanny intersections where digital objects most strenuously try to emulate objects in the real world — books, shelves, desk blotters, gaming tables — that Apple’s legitimately vaunted design sensibility breaks down. For its part, a pop-up animation of a lipid molecule might be enlightening — or it might merely be twisty and pretty. That’s why I almost want to say that, those heartfelt teacher testimonials at the start of yesterday’s show notwithstanding, it’s not the book Apple is trying to replace — it’s teaching.

Tools exist — they’re getting more powerful everyday — that allow us to treat digital objects as digital objects: to collect and organize them, to fashion stories from them, to turn them into bespoke devices uniquely tuned to unlocking the world’s mysteries. Apple wants to offer us those tools as well. Yesterday’s event also introduced iBooks Author, a free app for building iPad-native textbooks like Life on Earth. But increasingly, such vital aggregates can be engineered in classrooms, hacked together on the fly by teachers and students learning and teaching collaboratively. I’m thinking in particular of Zeega, an open-source toolkit for collecting media and telling stories, which is in the midst of development in association with metaLAB, the research/design group I work with at Harvard — but a host of other such tools exist or are on the way.

We can never count Apple out — the company’s visions have an implacable way of turning into givens — but the future is undoubtedly more complex. There will still be overcrowded classrooms, overworked teachers, and shrinking budgets in an education world animated by Apple. But I prefer to think of teachers and students finding ways to hack knowledge and make their own beautiful stories to envisioning ranks of students spellbound by magical tablets.

Matthew Battles is the author of Library: An Unquiet History and cofounder of HiLobrow. He is a program fellow at Harvard’s Berkman Center for Internet and Society, where he works for metaLAB, a research and design group investigating the arts and humanities in a time of networks.