It seems simple, when you think about it. Clay Johnson, author of The Information Diet, argues that our media problem is like our food problem: America is not obese because of bad food, but because we’re eating too much of it.

“It’s not like chickens off themselves, toss themselves into deep fryers, and then fly into our mouths,” he says.

“It’s not like chickens off themselves, toss themselves into deep fryers, and then fly into our mouths,” he says.

Likewise, Johnson says, we suffer from information overconsumption, not overload. We’re stuffing ourselves full of junk. It’s a business model encapsulated in The AOL Way, he said, the leaked memo that reduces journalism to pure, quantifiable data.

Johnson laid out his media nutrition metaphor Wednesday night at the MIT Media Lab in a panel discussion with two other people concerned about nutrition: Ethan Zuckerman, whose students at the Center for Civic Media are attempting to design nutrition labeling for news, and Sean Cash, a nutritional economist at Tufts University who studies the policy and politics of actual food.

Johnson likens big media to big agriculture. “They have to produce very cheap, very popular information. Just like our food companies weren’t concerned with nutrition…as much as their fiduciary responsibility,” he said. “We get media that caters to our base emotion of affirmation and fear. We want to be told that we’re right” — confirmation bias, in other words.

He demonstrated: A June 2011 Associated Press poll found President Obama’s support eroding with voters concerned about the economy, particularly women. The AP headline: Economic Worries Pose New Snags for Obama. The story that hit the wire was 827 words.

The Fox News headline? AP: Obama Has a Big Problem With White Women. That version of the AP story is reduced to two paragraphs.

“The recovering activist wants me to believe it’s because Fox has a conservative agenda,” Johnson said. “But the businessman in me knows that’s what gets people to click. That’s what their readers want to read.”

Every click is a vote, he says. Every search is a vote. More like this, please.

He demonstrates another example. What does Google suggest when you type in Republicans are…

And Democrats are…?

People aren’t going to Google wondering Are Republicans stupid? Are Democrats socialists? and searching for answers. They’re going, Johnson argues, to find affirmation. And media companies who cater to search traffic, who worship the pageview, will produce more media to satisfy that demand. Cheap, high-calorie, easy-to-manufacture media.

Zuckerman’s work to label the news, to help people make more healthful choices, is hard and complicated. Descriptive labels, rather than prescriptive labels, connote truth. But who is to determine the ingredients of a news story? And if we know how much of our news intake is opinion, celebrity gossip, and fluff, will that change our behavior?

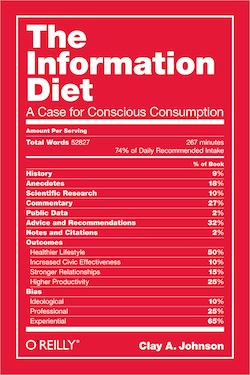

Johnson and Cash, the nutritionist, both take issue with labels. It’s not that they think they’re inherently problematic — a faux nutritional label for news is the cover of Johnson’s book, after all — but that they don’t solve the fundamental problem of overconsumption.

Johnson and Cash, the nutritionist, both take issue with labels. It’s not that they think they’re inherently problematic — a faux nutritional label for news is the cover of Johnson’s book, after all — but that they don’t solve the fundamental problem of overconsumption.

Cash said companies are reluctant to embrace labels voluntarily if they could be seen as bad for business. And consumers tend not to trust them if they’re voluntary. (What if Fox News disclosed that the following program was 85 percent fact, 15 percent speculation?) Mandatory labels, on the other hand — labels imposed upon companies by the government — can stir up resentment in consumers who don’t like being told what to do, not to mention, in the case of news, run quickly into First Amendment problems. Companies can also manipulate labels to suit their interests.

“I don’t know that we want government to give us those information content labels, and if we did have that information from government, how would we respond to it?” Cash said.

Johnson argues that nutritional labels serve a self-selecting audience. They don’t persuade people to change their behavior. “If you go into a grocery store as a fat person, as a person with a poor diet, it is not the case that a nutritional label is going to make you go, Oh, I should go on a diet!” he said.

Johnson cites a study published in the July 2011 British Medical Journal. After New York City enacted a law requiring nutritional labels appear on fast-food menu, the researchers tracked fast-food patrons in low-income areas to find out whether they made more healthful choices. By in large they didn’t, as compared to a similar sample studied before the law took effect. Only one in six people bothered to read the labels, they found, but those people did make lower-calorie choices. (The researchers conducted interviews and checked receipts.)

The business incentives for cheap media are obvious, at least if you buy Johnson’s narrative. But is there a market opening for news that satisfies a higher-quality news diet?

Johnson says yes, there is, and he returns to the food metaphor. He explains that Walmart is building a store three blocks from his house in Washington, D.C., and plans to sell organic food. His theory: “Walmart needs the Whole Foods customer to grow, because they’ve got no place left to grow in the U.S.,” he said.

In news, Johnson says, the market is saturated with cheap content. Johnson believes high-quality news should be paid for and that consumers — at least a subset of the population — are willing to pay for a differentiated product. Think of New York Times paywall subscribers as Whole Foods shoppers. “Maybe media will chase us like Walmart is chasing the Whole Foods customer,” he says.

Really? I asked him after the talk: Can most newspapers persuade enough people to pay for content on the web?

“I think that people are willing to pay for content. The success over the past four years of iTunes, which is now a $2 billion business, is people saying I want high-quality, ad-free content.” Same goes for HBO and Netflix, he said.

“Now with the iBookstore and the iBooks Author tool that they’ve just released a couple weeks ago, they’re making it so that me with my blog can write a 5,000-word piece and maybe sell it for a dollar. And instead of running ads on my blog to support myself, I can write — not even mini-books, but two- or three-page papers,” he said.

Johnson shoulders a lot of the burden for healthier living on the individual news consumer, not the producer. He acknowledges, however, that the target audience for his book — and the people in the audience at MIT — may not be the people whose info diets need the most help.

Pizza photo by Aaron Olaf used under a Creative Commons license.