How well does Tom Friedman translate into Chinese? (The world is flat, after all.) Or David Carr? The nuance of language is just one of the questions The New York Times faces as it makes its online entry into China. The Times is extending its global reach with the addition of cn.nytimes.com, a Chinese language edition that will offer a full slate of politics, business, culture and opinion.

Chinese readers will have a full slate of news from the Times, a mix of reporting from the mothership in New York along with stories produced by Chinese journalists. It means exporting the Times brand and, yes, its personalities like Friedman and Paul Krugman. But more importantly, at least to the Times, it may mean broadening the future of the Grey Lady through international audiences.

“We already have half a million readers on our website from China. It’s a big market for us already.”

It’s easy to understand why the Times would want to go into China — there are a lot of potential readers there. That also means a brand new audience for advertisers. It’s a land of opportunity, which is why the Times is joining the likes of The Wall Street Journal and the Financial Times in a yuan rush.

“We already have half a million readers on our website from China. It’s a big market for us already,” Joseph Kahn, the Times’ foreign editor, told me. “But there are millions, tens of millions of others who we think would be interested in a fuller New York Times report in Chinese.”

A look through early stories in the Chinese editions found Charles McGrath’s Nora Ephron obituary, a Friedman column on the Egyptian election and the latest on News Corp.’s split. (The site’s lead story at the moment is, remarkably, this Steven Erlanger piece piece interrogating the meaning of “socialism” in contemporary politics — cheeky, considering China’s a communist country where economic policy has long strayed from the traditional definition.) At the moment, they’re calling it a beta as they perfect new features, like the one-click English/Chinese tab on top of most stories. “We have a lot of people come to the site now and say one way it helps is to improve their English. So why not give them more of that,” Kahn said.

The Times doesn’t make blind decisions, and Kahn told me they’ve done surveys to see what the appetite is like for their journalism in Asia. Of course it also helps they’ve been able to sit back and watch the progress of Western competitors who have also taken a stake in China. “We’ve seen how some of those traffic and what reception they got in the market,” he said. “Part of our offering has been tailored from watching what others are doing too.” (The Journal and FT both have Chinese-language sites, for example.)

The plan is for two-thirds of the Chinese edition to be made up of stories from existing English-language stories found on nytimes.com, with the rest coming from Times staff in Beijing, Shanghai, and Hong Kong. Kahn told me the Times has seven staff reporters based in China, but the complete staff for the Chinese edition, including editors, reporters, and translators, will round out to about 35 people. The bulk of that staff will work on translation, which requires more than simple word matching.

“In all likelihood there will be times when access is restricted or certain article pages will be difficult to access there.”

On a global scale the Times already has The International Herald Tribune, which publishes in English, and India Ink, the nine-month-old English-language blog aimed at an Indian audience. China looks like a profitable next step thanks to a burgeoning middle class with money to spend. That’s a marketer’s dream. Denise Warren, the general manager of the nytimes.com, told a Times reporter they’ve already got luxury brands like Cartier, Bloomingdales and Salvatore Ferragamo on board. (While The New York Times is trying to show luxury ads to wealthy Chinese in China, oddly enough, The New York Observer is trying to show them to wealthy Chinese visiting New York.)

Yuezhi Zhao, a professor who studies media and communications in China at Simon Fraser University, said the shifts in government and rise of a middle class have created an opportunity for media companies like the Times. “There is definitely an emerging Chinese middle class who are willing readers of this kind of Western media,” Zhao told me. People in China are hungry for information and willing to look outside state channels or traditional media, Zhao said. Western media companies can act as a kind of wedge to get more stories out in the open, and Zhao expects some will be more than willing to be sources for companies like the Times. “There are willing Chinese sources high in the Chinese state willing to leak information and give access to things they are not giving Chinese media,” she said. Zhao points to the story now getting international attention about a woman from the Shaanxi Province who had a forced abortion after breaking the state’s one child law. A story like that gains traction in international media with the help of sources inside the government, she said.

Of course what makes publishing in China different is the ongoing threat of censorship. The Internet in China remains subject to the whims of the central government, which can slow or halt access to sites at they choose. But Zhao argues the situation is more nuanced than that. “I don’t think the simple framework of censorship vs. Western media really operates,” she said. “Yes, at a certain level. But looking at the bigger picture, I think it’s more complicated.”

In May, the Beijing correspondent for Al Jazeera English left the country after the government did not renew the broadcaster’s press credentials. While a number of outlets within the country self-censor or are subject to government review, Kahn was adamant that the Times would do nothing different from their U.S. operation. “Our feeling is, while we’re publishing ourselves in Chinese for the first time, our strategy is not affected by what China does,” he said. “We’re not a Chinese media company. We won’t submit to their censorship regime.”

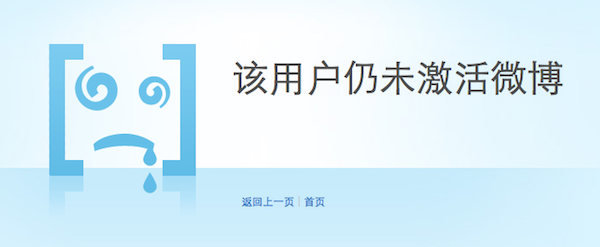

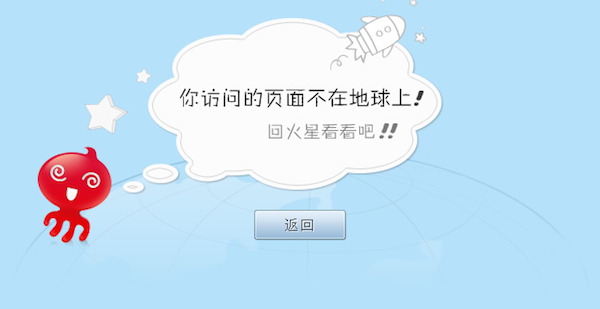

But while Times stories won’t face government editing, it’s the central authority that still has control over the Internet access available to most Chinese. Access to nytimes.com, just like many U.S. news sites, has been blocked in the past. And while cn.nytimes.com so far has remained unblocked, the same can’t be said for its social media presence there. Its accounts on major Chinese weibos — microblogging sites like Twitter — have been shut down, leaving behind only colorful “account not found” pages:

It’s unclear whether this is temporary or permanent; earlier, its Sina Weibo account was suspended for a brief period just as the China site was launched.

The Times is taking precautions, including keeping its servers outside the country. Even though Kahn is optimistic about dealing with the Chinese government, he said he expects the site will be blocked from time to time. “In all likelihood, there will be times when access is restricted or certain article pages will be difficult to access there. But that’s an internal matter for China,” Kahn said. “We’re just trying to produce a vigorous, competitive site that will be interesting to the Chinese and present a broad selection of the best of what we do.”