Every workday in Mumbai, 350,0001 home-cooked meals make their way from homes to offices at midday via a network of “culinary couriers” called dabbawallas. Single meals often pass through a dozen hands and as many distribution zones on their way to their destinations, where workers wait for meals made fresh at their homes.

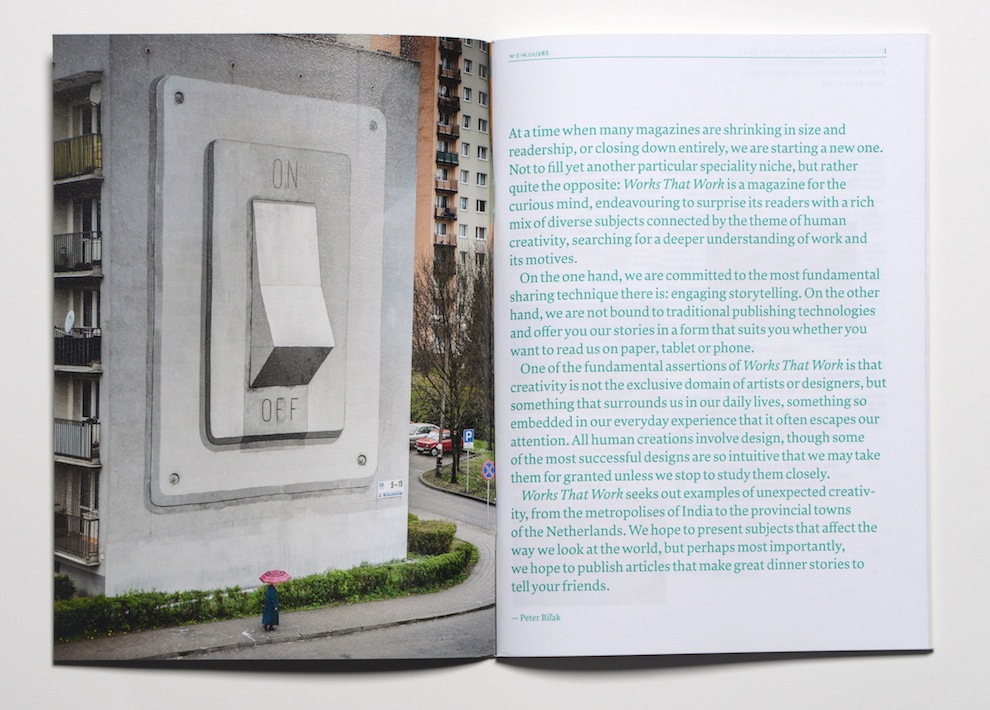

The phenomenon is chronicled in the first issue of Works that Work, a magazine published in the Netherlands that has become a distribution experiment of its own. Focusing on design and “human creativity,” the small magazine has found a way to get noticed globally by creating a beautiful digital edition as well as a creative way to distribute its print copies—gaining a lot of ever-coveted user engagement in the process.

The magazine’s founder, graphic designer Peter Bil’ak, calls it social distribution. It works like this: Fans of the magazine can ask their favorite bookstore to sell copies for a fixed price. If they agree, the reader then purchases 10 or more copies of the magazine at half price (print copies cost $20, while the digital version costs $10), and then sell them on to the bookstore at a price higher than what they paid but lower than the cover price. Reader/distributors keep the difference.

It’s using readers to do the jobs of distributors, which is not something that many other than die-hard fans will be willing to do. But it also keeps costs lower than they would otherwise be for a small publication.

“We looked at these logistic networks and we thought, if the magazine is about rethinking, about a different way of looking at design, this is how we should operate as well,” Bil’ak said.

It’s worked out well on a small scale for Works that Work, which published just 3,500 copies of its second issue in July. Half of those print copies were sold to individual readers, and the other half were sold in batches to readers and made their way to bookstores (and friends’ homes). Most of the 32 bookstores to take the magazine’s first issue are in Europe, but they also include spots in Indonesia, Hong Kong, and elsewhere. That doesn’t include informal distribution points or schools, like the College of Creative Studies in Detroit, where the magazines are delivered directly.

Social distribution has made for a surprisingly global publishing model for a small-scale print magazine, with modest numbers of copies “circulating” in Asia and South America. At the traditional art and design magazine he worked at before founding Works That Work, “we never had any sales in India, in Russia, in Brazil,” Bil’ak said. “They’re just trying to reach English-speaking countries — maybe Germany, the rest of Europe. It’s too costly, not worth the effort.”

The magazine’s global reach was carefully planned, down to the weight and binding of each copy to ensure ease of shipping. (“We were designing envelopes before there was even a magazine,” Bil’ak said.) Those concerns, though, weren’t even on Bil’ak’s mind when he started the project with nearly 30,000 euros raised by crowdfunding. Only after he raised the money did he ask the contributors: How do you want to read this thing?

“I didn’t mind if it was going to be an ebook or online or print. I was hoping for the print…but I didn’t really know,” he said. The verdict was in soon enough: more than 90 percent said they wanted to read either in print or both in print and digitally.

“It’s really readers who made the choice to make it a physical product, and we had to figure out how to get it to them,” Bil’ak said.

Their business model, though, isn’t quite as fixed. The magazine is still figuring out how it’s going to pay the bills. Its first issue included some prominent advertising, but Bil’ak tried to make the second issue work with only donations, which ended up only covering about half of the magazine’s expenses. (All contributors are paid; Bil’ak is not.)

Another way to foster user engagement is to have fans of the magazine host events for like-minded readers and sell copies, which is what happened a few months ago at a bar in Sao Paulo where designer Bebel Abreu helped sell 42 copies. She’s planning a second event in August.

“It’s something I like to read and I’d like my friends to have this experience as well,” she explained. “It’s not for the money. It’s because it’s cool.”

A debate over staples — yes, staples — illustrates that back-and-forth with readers. Many of its design-obsessed readers were not impressed with the first issue’s binding, which included visible staples. A 627-word blog post from Bil’ak followed, explaining the intricacies of saddle-stitch and hot-glue binding and including this video. Also following: a change to the binding.

“To create a community around the magazine, that’s equally important, that people feel a part of it, people feel engaged,” Bil’ak said.