LONDON — It’s lunchtime on a Tuesday, and the Monocle Cafe in the Marylebone neighborhood here is packed. All but one of the tables in the cafe’s lower level is occupied while the counters and couches on the main level are filled with customers eating sandwiches and drinking coffee.

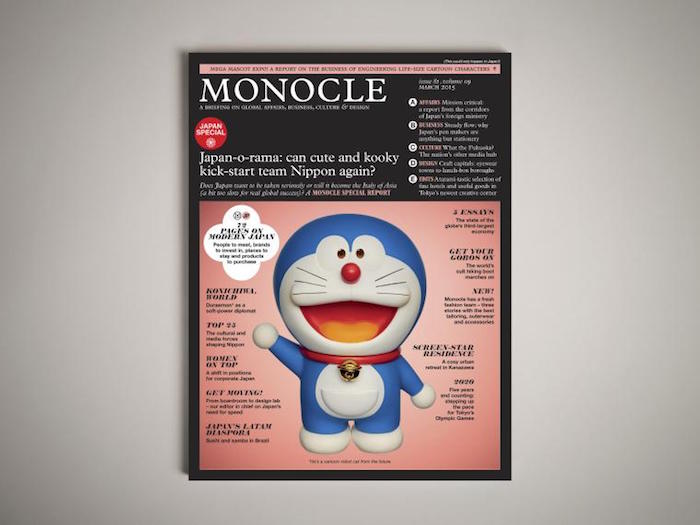

Monocle was initially conceived as a magazine in 2007 covering global affairs and a certain high-end global lifestyle. The brand has since grown to include Monocle 24, a 24-hour online radio station, retail shops in six cities around the world, cafes in London and Tokyo, and more.

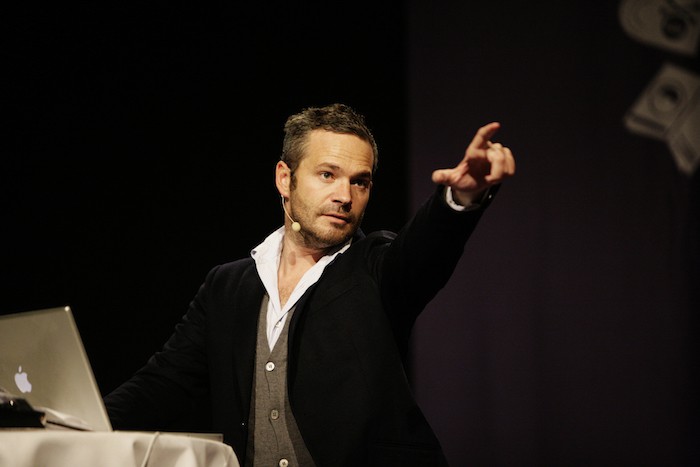

“You’re in this like-minded environment, but it’s not exclusive,” said Tyler Brûlé, Monocle’s founder and editor-in-chief, of the London cafe. “You have to know about it — or maybe someone walks in off the street because they want a good cup of coffee. But there is a sort of clubbiness to it, and you see people sort of talking and meeting.”

I met Brûlé at Midori House, Monocle’s London headquarters a few blocks from the cafe, and as he guided me on a tour through the office it was easy to get a spacial sense of the company’s projects. On the ground floor were the two radio studios from which Monocle 24 broadcasts. One level up, the editorial team was closing the April issue of the magazine. On another floor, Winkreative, Brûlé’s creative studio, was finishing up a redesign of Z, the Swiss newspaper Neue Zürcher Zeitung’s luxury supplement, and working on branding material for the Union Pearson Express, the new rail link connecting downtown Toronto and the city’s suburban airport.

Monocle was valued at about $115 million when the Japanese newspaper publisher Nikkei invested in the company last fall. Brûlé told me Monocle is “very profitable,” as the magazine has a circulation of about 80,000. (You can tell something about its audience’s habits and aspirations by noting it can describe an edition as “superyacht-sized.”

Brûlé said Monocle is considering adding new shops or cafes, but its next project, launching this spring, will be a Monocle newsstand near London’s Paddington Station. The kiosk will offer a curated selection of magazines and newspapers as well as global newspapers printed on-demand. Customers will be able to register online, request a printing of newspapers ranging from Norway’s Aftenbladet to The Australian, and then come to the newsstand to pick it up.

The newsstand is an experiment, but Brûlé said the company could create franchises and spin off the newsstand business if it succeeds. “It’s important for us to, I think, remind the market that — is it really a crisis of print, or is it a crisis of print distribution? And I would argue that part of it is the latter,” Brûlé told me.

What follows is a lightly edited and condensed transcript of our conversation, where Brûlé discussed the importance of print to his model, the thinking behind Monocle’s growth, and how he would approach The New York Times’ continued digital evolution.

I guess I would say the first thing is that we’re in a very fortunate position that we’re an independent publisher and we don’t have the commercial pressures of a big parent. And those commercial pressures can be two-fold: One is cost savings, but the other pressures are to go and chase after every new trend. We don’t have an issue of some digital guru or a friend or an investor or a board member who says, Why aren’t you slapping that little bird on the bottom of every webpage and every printed page? And why aren’t you putting that white F on a blue background on everything? So I think that’s also a positive, that we don’t have that influence surrounding our brand, that we have to follow the dictates of a big parent corporation, and that’s been the great thing from the very start.

We see that independence is really incredibly important to us, and has allowed us to be in the luxurious position that we’re in today, where if we decide to do a cafe, we do a cafe — because we think it’s the right thing to do from a brand point of a view, and also from a revenue position. Whereas often times people will say that maybe that’s not core to a digital strategy, or they would be arguing that people aren’t going to be drinking coffee anymore because people are going to be consuming it digitally.

But I think that’s the really exciting thing if you look back at our brand. We have the good fortune as well to be very nimble. If we want to go do something, we just go and do it. Of course, we can do all of that because we have a nicely profitable business, and that’s exciting, because we just organically reinvest in everything that we do without having to go to market to look for more money, and I think also rewarding for everybody on the team in this business as well.

So that’s just because we have a very different model. I think the scale of the U.S. — and I don’t know if it’s coercion or lack of creativity, but it’s always about chasing scale. I think “premium” has a bad name in the United States. Everyone wants to chase the mass. Particularly in media, everyone wants big numbers. We don’t want big numbers. We want engaged, quality readers, listeners, viewers. That’s what’s important to us.

What I think is important to us is that we can say: People spend $150 a year to subscribe to the magazine. There’s absolutely no way for them to get it discounted. They have to spend $150. And they’re probably more likely to fly on your airline, or buy your shoes, or book into your hotel, or purchase one of your cars than someone who is in a free channel.

And again, there’s no money in adding those extra editions. There’s the production cost: I think everyone was fooled in the beginning by thinking “Oh, we can just do one version for Apple and that’s it.” Now there are myriad different tablets, different operating systems, different formats, which means that what everyone thought just meant posting PDFs, now the demands mean there being moving video, streams, and all kinds of things.

We all know that it takes an extra six or seven staff to make a tablet edition and do it well. And we can’t recover that. The money’s not there every month to recoup that. An advertiser is not going to pay that much more money just because you’re offering them a tablet edition. In fact, they want it as added value. We haven’t found a way, and I haven’t seen anyone who’s making it work. And, certainly on this side of the Atlantic, you’re seeing a lot of the monthly magazines retreat from their tablet editions completely, because it’s just not bearing the fruit that we thought.

We have an app, but the app is there to support radio. And again, I guess our view is the same. Since the very beginning, since the day the magazine launched, there’s always been a paywall around the magazine, and that is because on one side journalism is expensive. We don’t think it’s that important to say that we’ve got millions of viewers on our site. If there are millions of viewers but no revenue stream around it, it’s not interesting. We want to create and craft an environment where we’re not getting into a discussion about cost per thousands. It’s the cost of a quality audience. That’s what we want our advertising partners to take.

Is the exposure great internationally off of Bloomberg? I think for a certain audience. Is it good on the weekends when our program was shown? Probably not. But it was a nice way of dipping our toe in the water. What it did do, more than anything else, is it gave us enough confidence to show that we know how to do broadcast. We have enough people in the building who are ex-television or, this was pre-radio, who even had radio background. That made us think a little bit.

We had a weekly podcast we were doing, called The Monocle Weekly, and we could see that there was some commercial life, because we were able to get some pretty good sponsors for that program. And it was a rather grand jump, but we thought: Why don’t we just build two studios and take this around the clock?

On one side, just thinking about the editorial opportunity, we think there’s something sitting between NPR — and NPR is great, but if you listen to a public service in the United States, they’re always appealing for your wallet for endless hours, which can be a bit grating. But there’s great programming. On the other side, you’ve got the World Service and lots of other state broadcasters, who are very good at what they do, but our view is that BBC, as wonderful an institution as it is, you see a political mandate to be very Africa-focused, be very Indian-subcontinent focused. And we thought our markets — Southeast Asia, Asia, North America, and Europe — there’s really room to do those markets much better.

We thought about digital — what digital channel or what digital application is the closest relationship to what that [pointing to magazine on the coffee table] does every month, where it’s very personal, it’s your Monocle, it has unique tone of voice, et cetera. And we thought audio is the closest thing, because it’s very personal, it’s very intimate, and it’s incredibly fast. It’s still the fastest medium. As long as you are articulate and persuasive, you’re going to get your opinion across faster no matter how fast you can clatter your fingers across a keyboard. So we like that as well.

We knew that, without huge startup costs, we could be in new places, be live, and be incredibly responsive. Radio just sort of seemed right. And it was an easy sell as well: We didn’t have to staff up in a huge way. We were able to get enough people around the microphone, and as much as we brought in professionals, we knew that we had a number of good voices and good minds also in our building. Then, of course, commercially we’ve been able to develop some really great partnerships as well with some major brands.

The distillation of all of that is we make a hell of a lot more money doing radio digitally, web-based, then we would just on running a regular website, a complementary site with live feeds and different columns and things like that. What we do now far outstrips what we could do with banner ads, preroll, or stuff like that.

For radio, it’s really much more of a North American play. We’re in like the 40 percent territory or more. I guess that has to do with podcasts and the uptake of Internet-based radio, which I think helps on one side. But what we’re seeing, though, is that we’re like 80-20 downloads versus live — but we believe live is important because it gives you just a different type of texture and sound. If you can go in and re-record your podcast a bunch of times it sounds perfect, but it also loses something — not to mention that it’s incredibly costly. When you do something live, I think you do sit up straight. You’re more erect. Your pitch is just different, because you get an edginess with live. There’s no question you make fewer mistakes when you’re live because you don’t have the nets and wires attached to it.

As a consequence of that as well, our live listenership continues to grow, which is great. Even when we’re out in the market, I’m surprised — even when you sit around the microphone you’re hoping people are listening to you in the live context, but often I’m thinking, They’ll be downloading this in an hour, or two hours, or over the weekend. But I’m really surprised you come across people saying, “Oh, I work at a law firm in San Francisco, and this is what’s on in our partner’s office, so we’re always listening to Monocle. So just collectively, you realize you’re at a cafe in Melbourne and that’s what’s on. So it’s good for us, collectively, to see that that’s an area that continues to grow, which is also what we want — because if you think about where in-car listening is going, among some other things, it becomes interesting to us.

And one day there was a flower shop around the corner that I always liked, and they were going out of business. It was such a small space, and I thought it would be horrible to see some big mass chain store try to bulldoze that and connect it to another shop halfway through. So we thought, what if we do this as a Christmas popup store? Now, six years later, it’s still there. It did well. And it was only after it opened that we thought it was interesting to use it as a bit of a laboratory to control your own distribution channel. We started to see how many magazines we could sell in that environment, and we started to expand the product mix.

It was just a different way of engaging with people, instead of just via email, because people would come in and they would give us a very, very good idea of who our readers and customers are. And then it started to make money on its own, so we opened another shop and another shop, and now we have six stores, probably with others on the horizon, and it’s turned into a wholesale business.

It’s 15 percent of our business now — it’s not small anymore. It’s a more serious part of what we do. Now what we think is interesting about it is that it controls the experience. People like to come buy their Monocle at the shop because they get it in a nice envelope, they get a nice bag. It’s maybe nicer than going to their local newsstand. It’s, of course, a moneymaking part of our business, but it gives us a different connection to our customer, which is key.

The cafe — we didn’t really have a cafe in mind until we were approached by a major retailer in Japan. They said, We’re opening a new department store, and it’s focused on men, it’s in Ginza — we’d love to do a Monocle Cafe. So we started to go through the exercise: If we had a cafe, what would we serve, what would we do?

And, of course, because it was Japan it was beautifully executed. We did all of the design. We did everything for it. It started to do well, and then a space became available down the street here, and we seized on the opportunity to take that space over. And now we’re really — I wouldn’t say wrestling, we’re not in any rush, but we just have a lot of offers, so it’s a question of are we going to own and operate them all ourselves? Or are we going to license them like we do in Japan? Again, it’s an environment: You might not know we have a radio station, and people will come in and buy the magazine and you’re among other Monocle readers as well. You’re in this like-minded environment, but it’s not exclusive. You have to know about it — or maybe someone walks in off the street because they want a good cup of coffee. But there is a sort of clubbiness to it, and you see people sort of talking and meeting. So that’s why we thought it would be interesting to do it in other markets. It’s not the case that maybe some companies would say, “it’d be nice to have as a brand extension” — we have to make money, so we want to make sure that all of these ventures that we do have a path to profitability.

I think The New York Times, you can see — it’s interesting that for all of their positive happy-clappy digital talk, all of the fuss given to the relaunch of the magazine and the scale and size of when they do the T supplements speaks to the fact that this is a very significant revenue generator for the newspaper. And I think they realized they had to pay attention to it, because someone obviously did a calculation that if we create some buzz around this, then maybe some advertisers are going to show up. Well, at least for the relaunch, they did.

But back to your question: I think The New York Times has been right to certainly look at putting a bit more in and around the print product. I don’t think there’s enough innovation in the newspaper itself. There’s so much innovation going into print technology. I think you can look at the international — I think they made a misstep with the mouthful that is the International New York Times. “IHT” also doesn’t even work, but people prefer the IHT to the INYT. Should it be the NYT? Is “International” important? They know they need to make a global play, but I think to do a proper global play, I firmly believe you need to have real, sizable editorial hubs to make that happen, just to respond to an international audience. I’m not sure they have that anymore.