Harvard Business Review is trying to walk a fine line: The magazine thinks it can raise the price for a subscription and still attract close to 100,000 new subscribers.

“Basic economics says you lower prices and get more customers; you raise prices you get fewer,” Harvard Business Review Group publisher Joshua Macht told me. “And our board members point this out to me. But there’s this defying gravity idea, and the reason why I think it’s possible…is for the last five years, at least, we’ve been in this conversation with subscribers.”

As of the end of 2014, HBR had a paid circulation (print plus digital) of 263,645, according to the Alliance for Audited Media. A yearlong U.S. subscription to the magazine, including access to its tablet edition, costs $99 annually. (It’s more expensive elsewhere.) The magazine increased its subscription price in 2013 from $89. Though the magazine says its paid circulation has grown by 17 percent since 2011, HBR now wants to boost its circulation to 350,000 — while also upping the subscription price again to $109.

HBR thinks readers will be willing to pay more for a subscription because the magazine is adding new products it hopes will offer readers additional value for the added cost.

Last month, HBR launched its Visual Library, a collection of the magazine’s charts, graphs, and slide decks accessible only to subscribers. It’s also in the early stages of testing out a concierge service that will allow users to request personalized collections of stories from the HBR archive.

“What we found is that, as we’ve rolled these things out, we’ve been able to move the price up,” Macht said.

The new products are part of a larger overhaul from HBR. Last fall, it introduced a redesigned website, and it’s currently in the midst of a print redesign — its first since 2010. And by the middle of 2016, HBR plans to roll out what editor-in-chief Adi Ignatius called “a pretty dramatic strategic rethink.” It’ll likely include more new products and a potential reduction in how often HBR comes out in print. HBR now prints 10 issues per year.

“Look, at some point, we’re going to cut back print frequency,” Ignatius told me. “That’s a surprise to nobody. So I think the exact numbers and the exact thing, we’ll figure that out and announce it when we do. The middle of next year, we’ll unveil something.”

HBR wouldn’t go into specifics about what it’s planning, but some of the projects it’s now testing and releasing figure to play roles in whatever the rethought Harvard Business Review looks like. “People want practical, applicable stuff,” Ignatius said. “So we’re shifting kind of what we do. Obviously the core is still big idea pieces — that’s what we do and what we will always do. But all this complementary stuff is real important, and our mix is changing and we’re developing in-house capabilities to create all this stuff.”

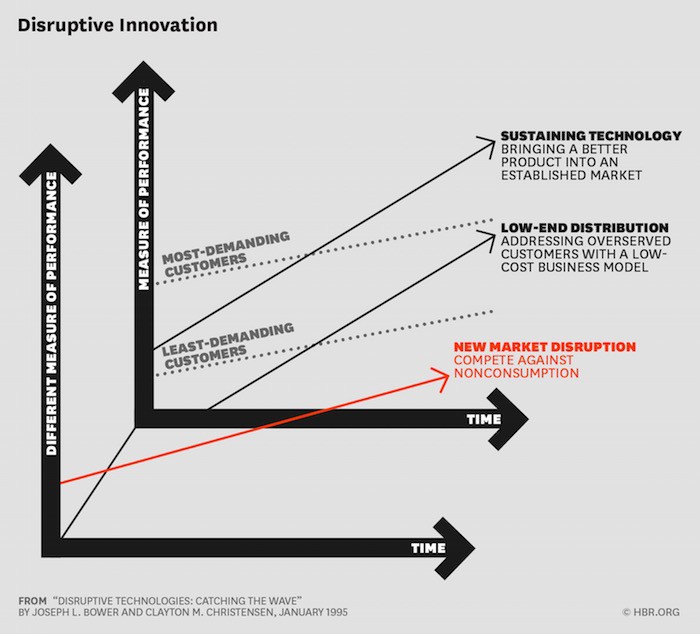

The Visual Library debuted for all subscribers in early June after a nearly two-month-long soft launch. The library opened with about 100 charts and infographics and 11 pre-made PowerPoint presentations on topics such as “Navigating the Cultural Minefield” and “Reinventing Performance Management.” Why make your own deck for the quarterly TPS-report meeting when you can lift HBR’s?

The slide decks went through nearly a year of development, said Eric Hellweg, HBR’s editorial director and managing director of digital strategy. The first slide deck HBR produced for the visual library was 96 slides long, but he said they’ve since shortened the decks and templated the process, making it easier for editors to produce them.

“We’re trying to make it as easy as possible to provide the tools where possible so it’s not a heavy, heavy cognitive lift or time sink for editors,” Hellweg told me.

The concierge service, meanwhile, is in the earliest phases of development. HBR is working with the Harvard Business School’s library to develop the product, and it’s begun testing it with just a handful of subscribers. (Here’s a good place for a disclosure: Just like the Harvard Business Review, Nieman Lab is also affiliated with Harvard University. It’s a big place.)

Essentially, subscribers would request research on a certain topic and within 24 hours, HBR would provide a human-curated list of content that matches with the request. It’s still deciding whether it would be part of a normal subscription or if it would charge more for the service.

“We are figuring out what kinds of questions people have,” Ignatius said. “We can build a database or wiki that makes it easier to respond to subsequent questions that are similar.”

Ignatius said the concierge service could play out in one of three ways: People aren’t interested in it and HBR would drop it; there’s a huge interest in the service, and HBR has to figure out how to meet demand; or there’s a perfect amount of interest and HBR can simply add it to a subscription.

Regardless of what becomes of the concierge experiment, HBR, like many legacy news organizations, says its committed to making the most of its extensive archive, which dates back to the magazine’s founding in 1922.

HBR has a big publishing business, and frequently publishes books and ebooks that are collections of reprinted HBR articles. But since its web redesign last fall, the magazine has begun thinking more actively about how to best use its archive. “The archive has gone from being something that’s just kind of there, and people bought reprints, to something we’re actively thinking about and working with,” Ignatius said.

Subscribers have access to the magazine’s archives online, and both subscribers and users who are just registered with HBR can save any article to what HBR calls “My Library,” a personal dashboard to save and share stories. HBR will also recommend you stories based on what you say you’re interested in. But the magazine wants to further personalize its offerings, so if it knows, say, you’re the chief marketing officer of a large company, HBR will surface articles relevant to your work.

“We’re thinking about ways that maybe we could make that data available to other subscribers,” Hellweg said. “Obviously, anonymized. But if you’re a chief marketing officer, do you want to see what other chief marketing officers are reading? So really kind of finding ways to use that data pretty substantially.”

When HBR redesigned its site, it also changed the approach to its paywall. Anonymous users can access up to 5 articles per month. Users who register get 15. By encouraging free registration, HBR is trying to move some of those readers along the path to subscribing, but it’s also able to get information on how different segments of users are actually using the site. (The site says it gets about 4.5 million unique visitors per month.)

For example, HBR has discovered that subscribers are the most likely cohort to go to the HBR homepage and use the site’s search function. As a result, HBR is going to prioritize improving search to benefit subscribers, Hellweg, the director of digital strategy, said.

“Our fiscal year starts on July 1 [today], and we’re planning out a set of activities and we’re going to make sure that search is going to be as good as it can be, if that’s where subscribers are going. And we’re also going to try and find interesting ways that we can maybe make the newsletters more apparent to people and see if we can find ways to drive signups there, given some of that correlation,” he said.

And though its recent redesign made HBR’s website responsive, subscribers are still primarily accessing the site on desktop — as you might imagine for an audience heavy on office dwellers with big screens. About 35 percent of HBR’s total traffic comes from mobile, but Hellweg said that when you only look at the most popular recent stories, about 60 percent of reading is on mobile — meaning that people reading the archives and using HBR’s other tools are even more concentrated on desktop.

“That’s the fat end of the tail — and we have a massive archive — and it tapers down pretty considerably after that,” Hellweg said. “So we’re seeing the majority percentage of content consumption from our most popular stuff coming through mobile, a significant amount of that is coming through social.”