The bankers are now hired. Is the early 2019 newspaper chain M&A face-off now getting serious?

It’s reminiscent of an earlier brand of warfare. Newspaper chains — all cutting desperately, each facing a shortening deadline to make a “digital transition” — line up their dealmaking armies, swords sharpened if not yet crossed.

Gannett, having rejected the hostile takeover bid of Alden Global Capital, has decided to hire Goldman Sachs to advise it on the next rounds of dealmaking, I’ve learned. Goldman participated in Thursday’s Gannett/Alden meeting, alongside Greenhill, its ongoing deal-advising firm.

As that meeting happened, Alden, with its banker Moelis, filed an alternative slate of directors for election at Gannett’s upcoming annual meeting. That action, though, is just another uncertain indicator of whether it’s Alden’s true intent to acquire Gannett, a number of insiders have told me.

As Bloomberg’s Brooke Sutherland summed up well in her lede on Alden’s slate: “The more MNG Enterprises tries to prove it’s serious about buying Gannett Co., the less credible it looks.” (MNG, née MediaNews Group, is the name Alden uses for its newspaper holdings, conglomerated after two bankruptcies.) Remember, Alden’s initial move against Gannett said both that it wanted to buy the company and that Gannett should begin “a review of strategic alternatives to maximize shareholder value.” That’s a baffling combination — do they want to buy the thing or not? Then Alden failed to show Gannett enough financial wherewithal to actually fund an acquisition. Then, after just one rebuff, it filed the alternative slate. Of course, the deadlines of the corporate calendar drove the board filing — but still, it all looks maladroit, clumsily rapacious for the cutthroat Alden.

On the sidelines, Tribune Publishing — an active would-be seller for most of the last year — is waving its shiny, largely debt-free balance sheet Gannett’s way. It’s now advised both by Lazard and Methuselah Advisors LLC.

Curiously, in this small media banker world, switcheroo is fair game: Two years ago, Methusaleh was advising Gannett as it company fended off a hostile bid from Michael Ferro’s Tronc — the company now known (again) as Tribune. And who was representing Tronc then? Goldman. Importantly, all these parties know one another — and the innards of these companies — well.

While a Gannett/Tribune merger looks like one of the likeliest Alden alternatives, Goldman will look broadly at the industry landscape and where Gannett best fits in it — whether as a seller, a merger, or a buyer.

As these three companies line up, a fourth — McClatchy — is looking for its own place on the shrinking battlefield, as I detailed as February began.“It could be weeks — it should be weeks,” one of the participants told me at the end of last week. “These parties know a lot about each other already.” But all the same questions about valuation (how can you best forecast these companies’ earning power over the next few years?) and financing remain. (How much is it back to the drawing board? “A lot has changed in a year,” another insider said. “In some ways, we have to start all over.”) So any timelines remain TBD.

None of these companies comment on the action, of course, beyond issuing standard-letter comments on each other’s action, as last week when Gannett decried Alden’s board slate and formally rejected its $12-a-share January offer.

Each company has a lot on its plate right now. Bad budget projections for the rest of the year have made this the season for workforce cuts, with McClatchy’s, Gannett’s, and GateHouse’s all making the news. These companies are also preparing to release their full-year 2018 numbers, scheduled over the next several weeks, which will all be down. The biggest investor questions will revolve around forecast earnings for 2019.

While none of these chains has reported yet, The New York Times Co. did last week — further demonstrating how much it has separated itself from its former print brethren. With remarkable numbers, the Times showed new strength that propelled its share price beyond $30 in more than a decade. Remarkably, in doing so, it grew revenues 6.2 percent year over year — a number few other newspaper companies could even realistically daydream about. Digital advertising climbed 11.3 percent for the year, with print advertising down only 5.3 percent.The Q4 numbers, which included the usual end-of-year holiday bump, were even better, up 23 percent year over year. In Q4 2017, the Times pulled in 17 percent more money from print advertising than from digital. In Q4 2018, the ratio was reversed: It generated 17 percent more money from digital advertising than from print.

Those numbers — oh, and its 3.4 million paid digital subscribers (and 4.3 million overall, including print) — are something whatever execs are left at Gannett, Tribune, McClatchy, and Alden can only marvel at.

We could construct quite a chart of the divergent trajectories of the Times against the chains, individually or collectively. But you hear almost no one in those chains talking about why The New York Times (or the Financial Times, or The Washington Post, or The New Yorker) has been so successful, and what their own companies might apply accordingly. Fundamentals like:

There are plenty of other lessons to apply, but I’ll stop there for now.

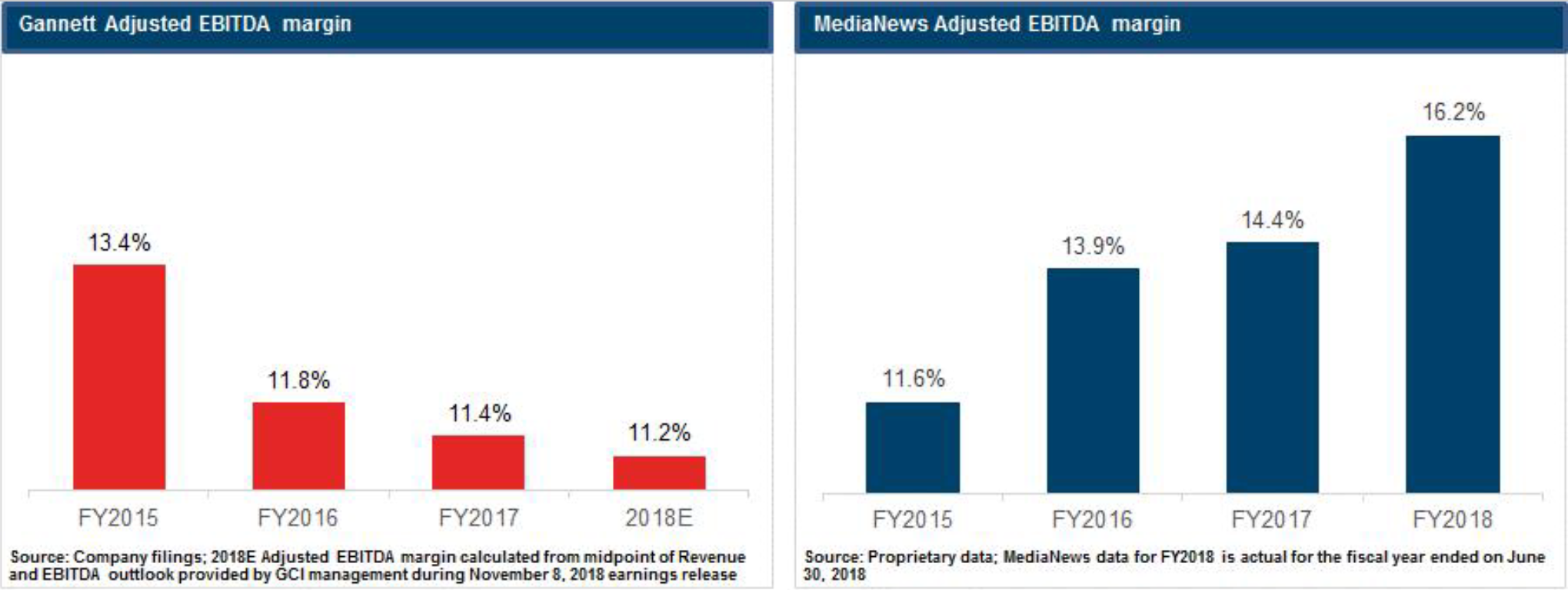

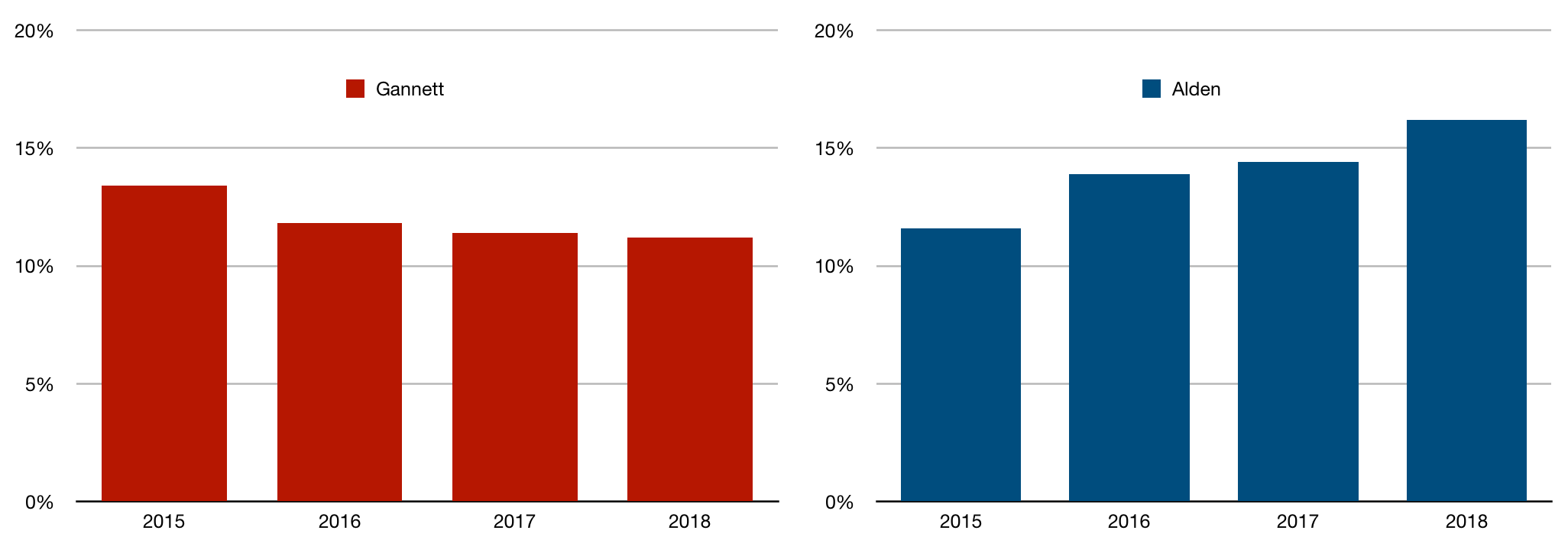

Instead, in this M&A quagmire I’ve called the 2019 Consolidation Games, we get charts like this:

This chart, offered up by Alden Global Capital as it presses Gannett to accept its buyout offer, says so much in so few words.

First, let’s just take note of the enormous violence being done to the art of data visualization here — the non-zero baseline, 11.8 and 11.6 percent being the same height, but 13.4 percent being higher than 13.9 percent. The graphics people at their newspapers would do better. Here’s a more accurate portrayal of their numbers:

Alden points to its MNG EBITDA, or earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization. “Ours keep going up,” it essentially says, “while yours at Gannett decline. Prima facie evidence that we can manage decline better than you can.”

The numbers tell us much more.

Some history: After I reported on Alden’s outsized profits here in May 2018, the company complained that the numbers were wrong — “we don’t know where they came from,” “they do not reflect the true cash flow of these businesses,” “those aren’t the real numbers” — and that actually Alden’s profit margin was nothing special.Some quotes from a June staff meeting at The Denver Post with Joe Fuchs, the board chair of Alden’s Digital First Media (emphases mine):

We don’t produce the kind of profit margin that some of the competitors do, but we are in there to be sort of be in the midrange of what I would call profitability…

So, what is an appropriate profitability? You know, that’s a real tough question to ask. I’d say, I said to you before, we compare our numbers with everybody and then some private companies when we can. And we’re sort of in the middle.

…trust me, we do not want [the Post] to fail, we want it to be vibrant we want it to be a force in the community and yes, we want it to be profitable in the range that is sort of the norm within the industry. Nobody’s driving it to be the most profitable.

Now, instead of saying it’s only a middle-of-the-pack profit maker, Alden has reversed course and points with pride to its top-of-the-industry profiteering.

Further, Alden does manage to show that while both companies have cut and cut — with staffing at some Gannett newspapers no better than the more publicly maligned Alden-owned ones — Alden’s success in squeezing accounts better for itself. Why invest in what it sees as Gannett’s digital marketing businesses of dubious profit potential when you can line your pockets more thickly?

So where do we think the action goes next?

By all accounts, Gannett — with lame-duck CEO Bob Dickey retiring and board chair John Jeffry Louis shouldering the burden of leadership — prepares to do battle with Alden. Between now and its annual meeting (expected this spring, though the date is as yet unannounced), Gannett wants to make sure it can defeat Alden’s board slate, and that its directors can maintain control of the company’s fate. That’s job one for Goldman. The fact that Alden baldly put up a group of its own insiders — including Joe Fuchs and former DFM CEO Steve Rossi — helps Gannett’s argument that the slate is simply meant to deliver Gannett to Alden, and not “pursue Gannett’s best interests.”

This morning, Gannett increased its aggressive response to Alden’s offer, on numerous grounds, including these gems:

At least three of MNG’s candidates may be legally incapable of serving on the Gannett board under applicable antitrust laws, given their roles with MNG, which is a competitor of Gannett. Several other elements of MNG’s notice to Gannett raise additional concerns regarding the credibility of its proposal, including nominating 78-year-old Mr. Fuchs, who exceeds Gannett’s mandatory retirement age applicable to all directors, and MNG’s statement that it reserves the right to substitute director nominees in direct contravention to Gannett’s bylaws.

But it still has to prepare the defense.

The question then: Hamstrung by that defense and less-than-robust leadership, will it have enough bandwidth to seriously enter new talks with Tribune Publishing and its new CEO Tim Knight? Knight, with the backing of his board, his advisors, and 25 percent owner Patrick Soon-Shiong, would like to put together a Tribune–Gannett merger. And, we can expect, he’d like to become CEO of the combined company, which would by far be the largest newspaper chain in the country. (If Alden managed to snatch the CEO-less Gannett, who might lead that combined company? Two sources this weekend suggested that same Steve Rossi, who retired as Digital First Media’s last CEO in 2017.)

The path is there. Combine the companies, claim $100 to $150 million in synergies over two to three years, and make the case that it’s in the best interest of shareholders, employees, and readers. And proclaim that it’s a better deal for shareholders than Alden’s offer.

Gannett and Tribune negotiated last year, but talks fell apart on valuation issues (how much of the merged company each side would get) and on whether ex-Tronc chairman Michael Ferro would get a board seat.

That was 2018. Sources say Ferro, who still heads a group that owns 25 percent of Tribune, has now dropped his demand for a board seat. His hand-picked CEO Justin Dearborn is gone, dispatched last month as damaged goods in order for Tribune to finally get a deal done.

One would-be dealmaker offered this arithmetic. Combine the cash flows of Gannett (around $300 million), Tribune (around $100 million) and merger synergies (let’s say $100 million), and that can support the financing — in addition to stock swaps — needed to get a deal done.

The companies have each done their analyses on how a merger might work — even though the industry’s worsening state, updated revenue forecasts, Tribune’s plummeting share price, and the threat of recession will all force revisions. February and maybe March should be about these companies and their advisors working on those two issues: valuation and financing.

What’s a split of the new company acceptable to both parties? Could the deal be done as a stock swap, or it would necessitate new financing? If so, at what cost?

That’s the money side. But there’s also that other element in any negotiation: time. It’s fleeting, faster than all the print ad dollars exiting newspapers. Will Gannett be able to deeply engage with Tribune at the same time it battles Alden?

Can it afford to spend that time? Can it afford not to?