It’s easy to make broad claims about the American media. “They’re all just a bunch of leftists!” “It’s all run by fat-cat corporations!” “They don’t report the facts like they used to — now it’s all their opinion!”

The people making these claims aren’t always responsive to facts, but a broad new linguistic analysis out today tries to produce them. How is media today different from what it used to be, back in that simpler pre-web age?

The report, from the global policy nonprofit RAND, includes a host of fascinating findings, but the broad strokes are these:

Newspapers haven’t changed much. Television news has changed a lot, putting more focus on emotion, first-person perspective, and immediacy. Cable news is like TV news squared, with more argument, personal opinion, and dogmatic positions. And online news shares qualities with both newspapers and TV news, favoring subjective views and argument but also “heavily anchored in key policy and social issues” and “report[ing] on these issues through personal frames and experiences.”

For this study, RAND looked at three types of news media: TV, print journalism, and online journalism. It gathered a giant pool of articles and transcripts from across 15 news outlets, then analyzed the text using RAND-Lex, “a tool for textual analysis that combines machine learning used to identify patterns in word use, tone, and sentiment with qualitative content analysis.” (The new report is something of a follow-up to RAND’s previous report on “Truth Decay,” which diagnosed, among other things, “a blurring of the line between opinion and fact.”)For print journalism, the team looked at front-page articles from The New York Times, The Washington Post, and the St. Louis Post-Dispatch (all of which have archives going back to 1989 available in LexisNexis); transcripts of the flagship news programs on broadcast networks CBS, NBC, and ABC and of prime-time programming on cable networks CNN, Fox News, and MSNBC (with transcripts beginning as early as they were available in LexisNexis, ranging from 1979 for ABC to 1996 for Fox News, MSBNC, and NBC); and homepage stories from digital-only news sites BuzzFeed, Politico, The Huffington Post, Breitbart, Daily Caller, and The Blaze, from 2012 to 2017. (The goal with online news was to “study a sample of the most-consumed online outlets on each side of the political spectrum…we did not try to create a representative sample that was fully balanced in type or partisanship of coverage.”)

Here’s what they found. (The full report contains much, much more information on how exactly RAND-Lex works and looks for patterns across thousands of articles.)

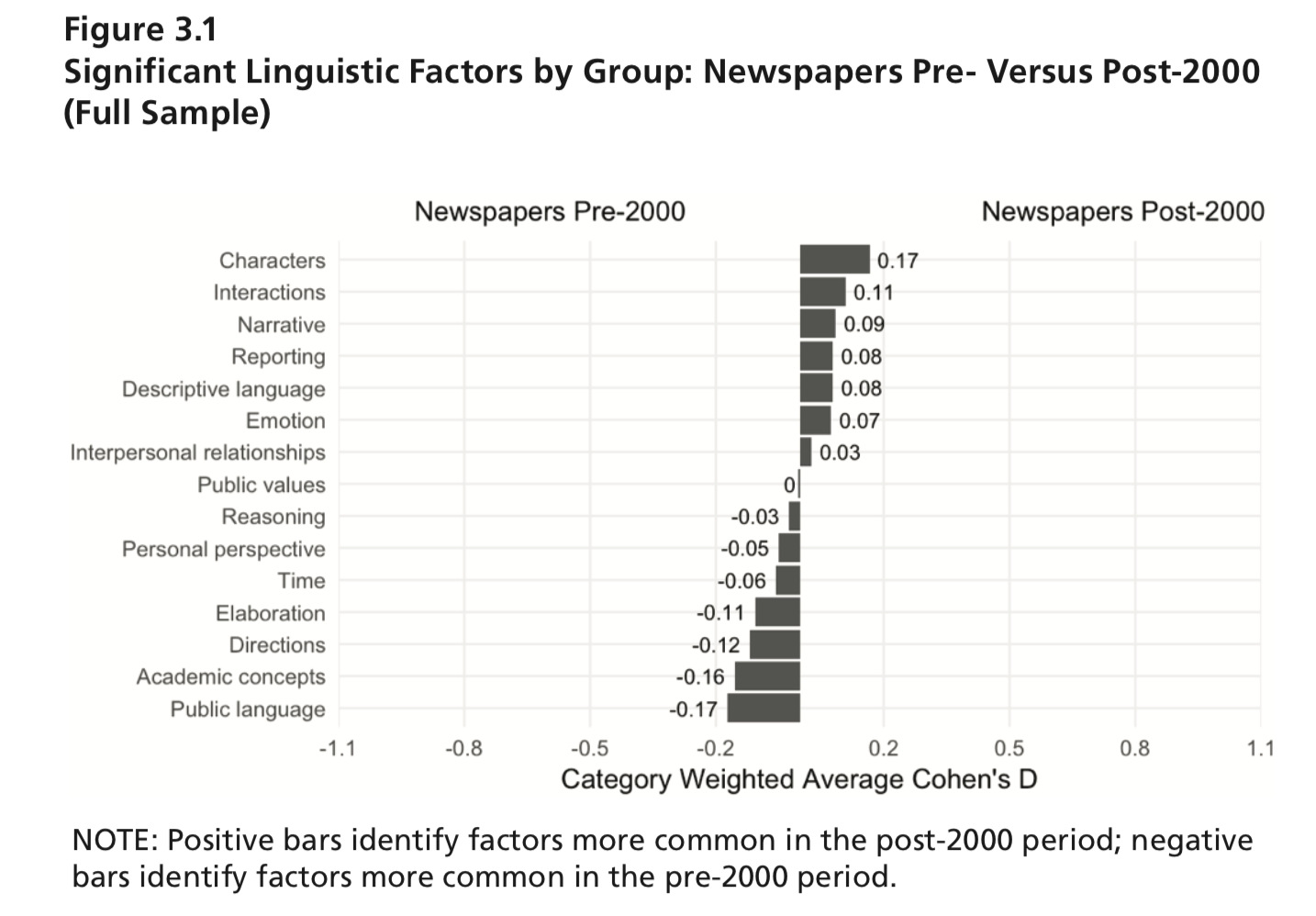

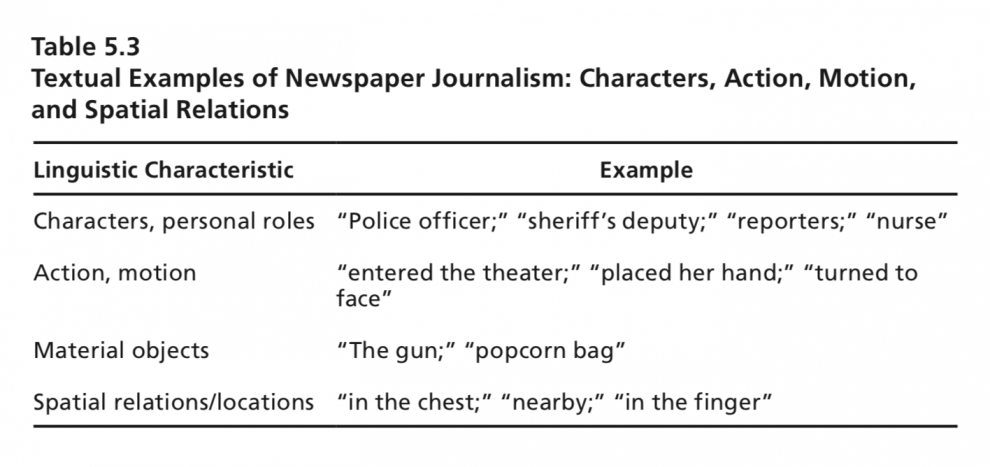

Of the three categories of content that the researchers looked at, print journalism has changed the least since 2000: Newspaper reporting is largely the same as it was in the past at least when it comes to front-page stories, with changes “less as radical departures and more as subtle shifts in emphasis and framing.”

What changes there have been might please those in journalism who’ve been pushing for more use of storytelling over the past few decades. Post-2000 stories use more characters, more narrative, and more human interactions.

From the report:

Text in our sample from the pre-2000 period exhibited more public language (references to authority sources), directive language, and academic or abstract concepts. It also exhibited more language of immediacy (e.g., “right now”). Meanwhile, the post-2000 language in our sample seemed to have a comparative emphasis on interactions, characters (narrative), and emotion…

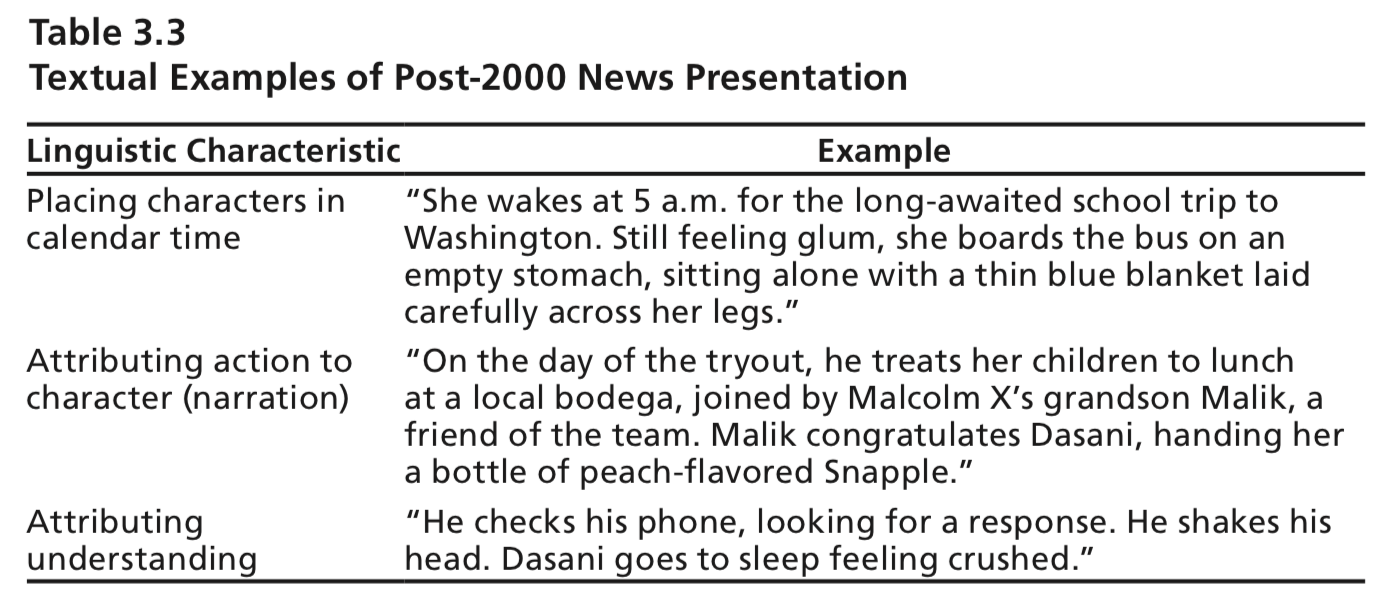

Post-2000 newspaper coverage was marked by two elements of narrative storytelling. The first is simple, value-neutral attribution of behavior to characters: telling the audience what a character did, said, or thought. The second feature was a tendency to place stories in dated time (e.g., Thursday, the next week, or September 11, 2001). A good example of those types of language combined is the in-depth profile, laying out the day-to-day life of someone whose circumstances illustrate a pressing public issue. Even as many aspects of newspaper coverage remained the same, then, there does seem to have been a shift from coverage focused on numbers, authority, and imperatives to coverage that uses storytelling and such contextual details as dates to portray an issue.

As examples, the report’s authors cite The New York Times’ 2013 profile of a homeless child named Dasani as a good example of post-2000 news presentation, and this 1994 Post-Dispatch story as its pre-millennial analog.

Despite some shifts like this, however, the authors stress that “the overarching pattern for our newspaper analysis is one of stability…newspaper content has been characterized by much consistency over time.” In other words, the post-2000 explosion of digital writing hasn’t had that much of an impact on newspaper reporters and editors — even though a screen is usually the first place their words reach readers today.

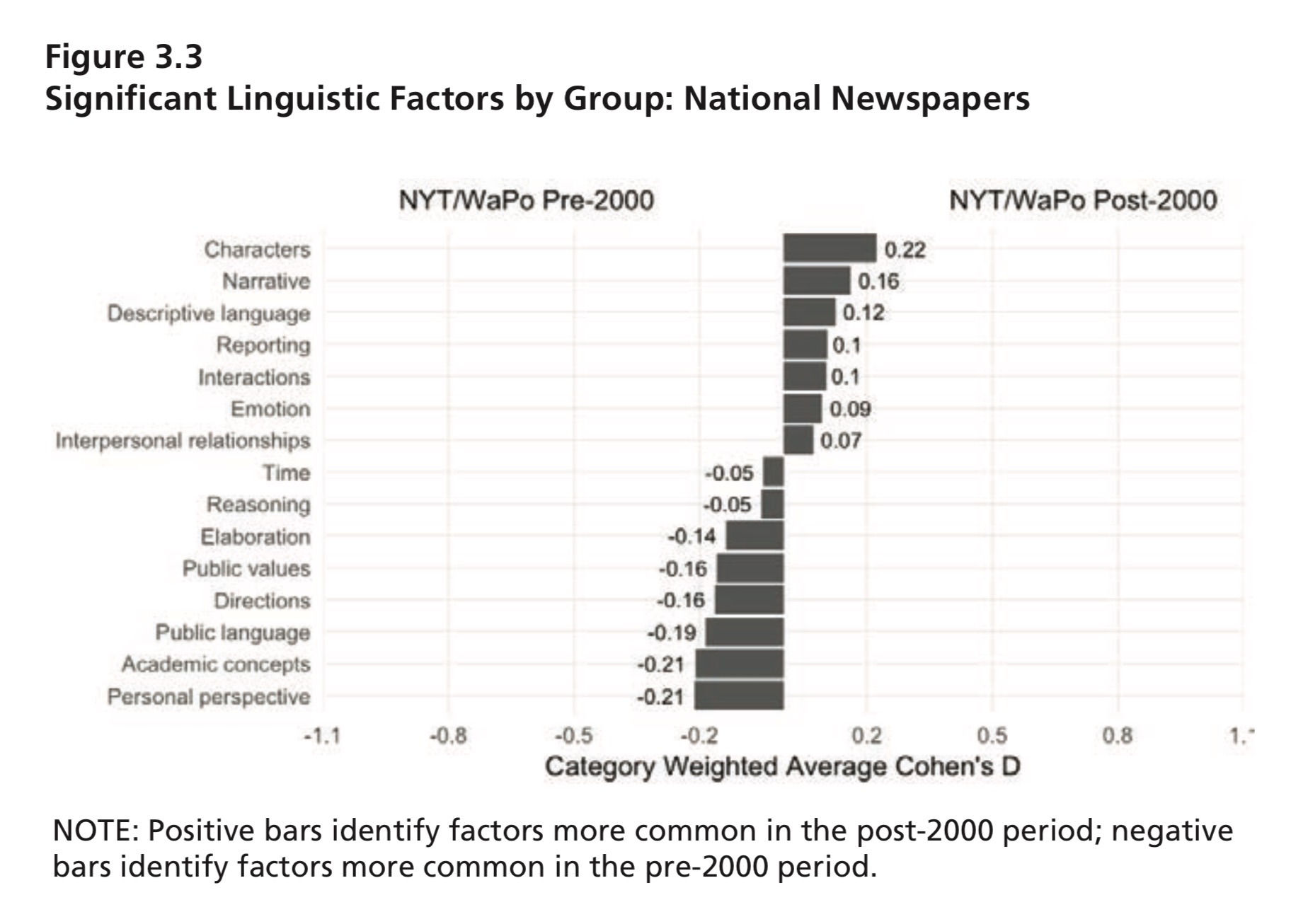

What if you only look at the national newspapers in the analysis, the Times and the Post? The overall patterns are very similar to the entire newspapers sample, but the decline in the use of personal perspective is notably larger.

Unlike with newspapers, RAND sees major differences in broadcast TV pre- and post-2000. On broadcast TV:

In the pre-2000 period, broadcast news was more likely to use academic language (including abstract concepts), complex reasoning about causality and contingencies, and argumentative reasoning (denying and resisting opposing arguments). The pre-2000 period also used more precise language: specifiers that made clear all, some, or none of the things being discussed (in other words, the language makes clear what is and is not covered), along with examples of what was being discussed. Finally, all this was grounded in a shared public language about authority sources for public life (again, as in newspaper reporting), and about public vices, such as bribery, corruption, or violence.

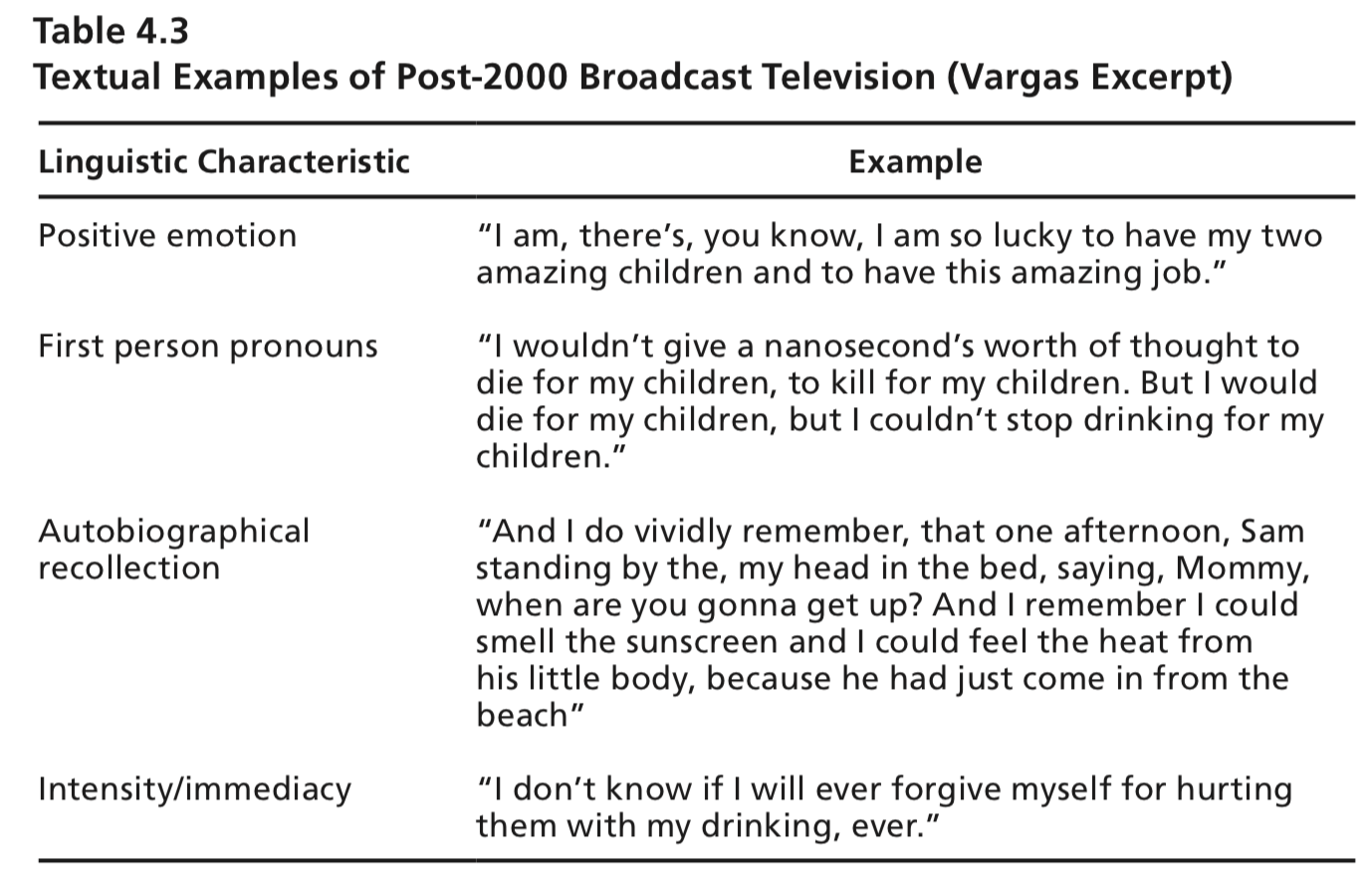

After 2000, broadcast news loses much of this academic and precise tone. It becomes more conversational, with more extemporaneous and less preplanned speech. This also has meant more subjectivity: less straight reporting of preplanned stories, and more conversation among newscasters, between newscasters and expert guests, and between newscasters and the audience. Such conversations are interactive and feature personal perspectives; speakers interact interpersonally…

Lastly, we found increased positivity — more mentions of “love,” people having “a shot at” a better life, or cases where “people are making a real difference.” We can describe this increase in positive language, but we are not sure why it has occurred and cannot connect it to other features of broadcast news in the post-2000 period. It is possible that this increase is related in some ways to the increasing appeals to emotion noted in the post-2000 newspaper corpus.

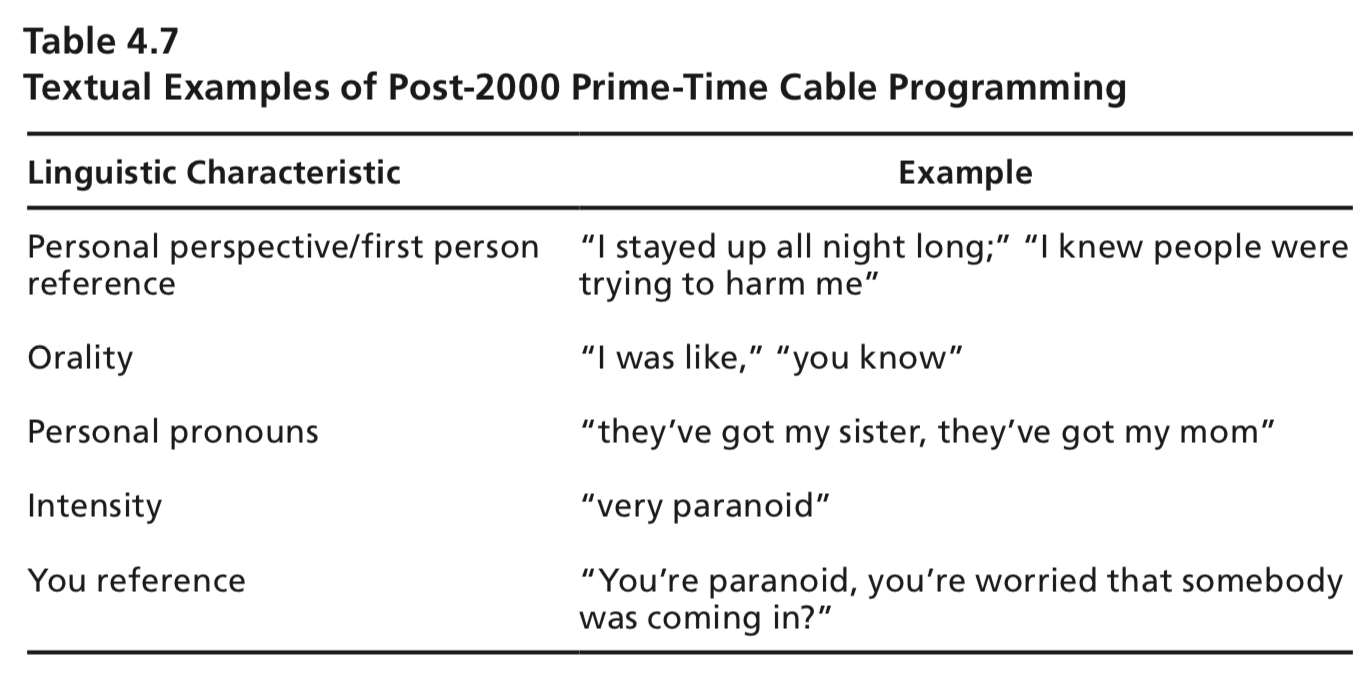

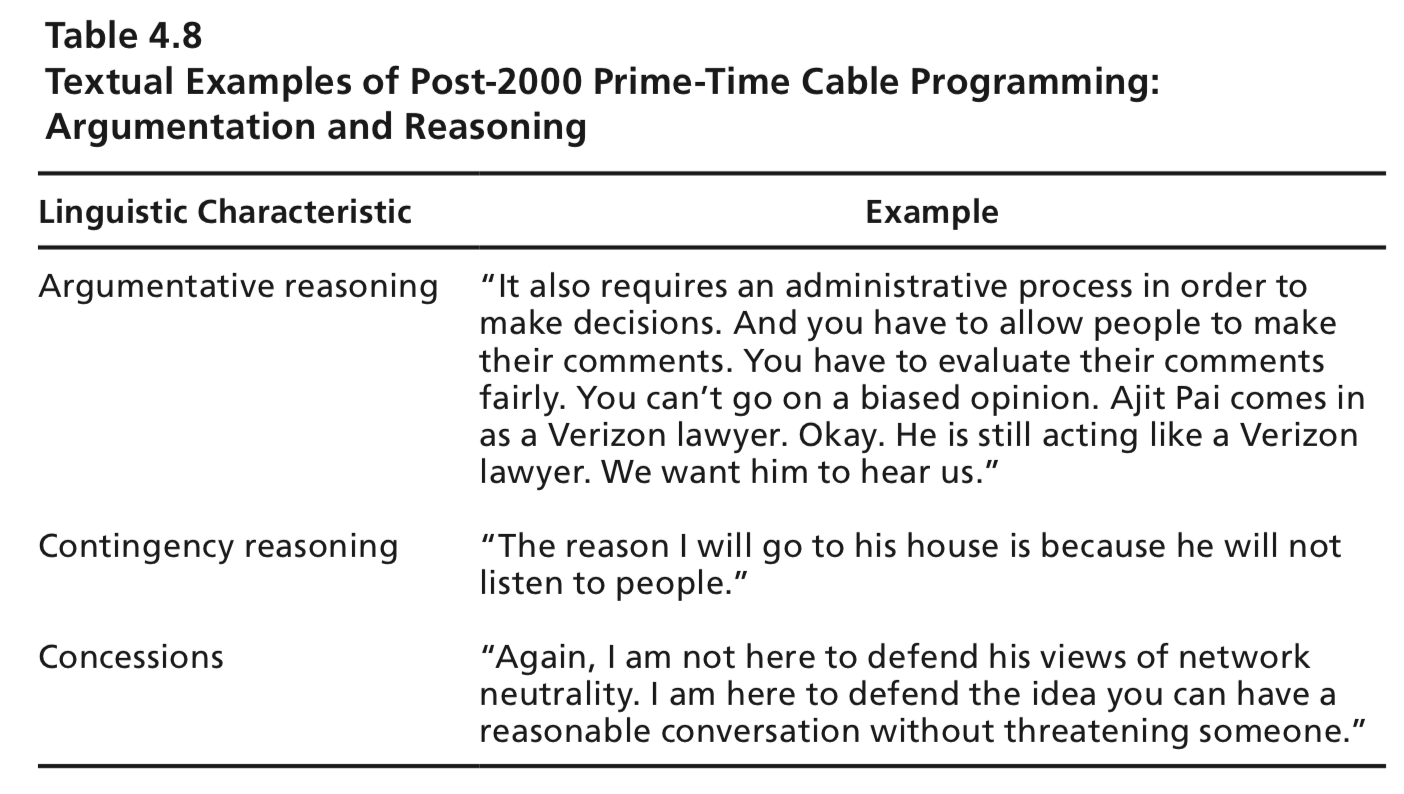

Cable TV, as anyone who’s watched it could guess, amps up the subjectivity and the back-and-forth: “Prime-time cable programming is characterized by more-argumentative language, more-personal and subjective exposition of topics, more use of opinion and personal interaction, and more-dogmatic positions for and against specific positions.”

(Note that the above figure is comparing broadcast vs. cable — not, as the two similar-looking figures above are, the pre-2000 period vs. the post-2000 period.)

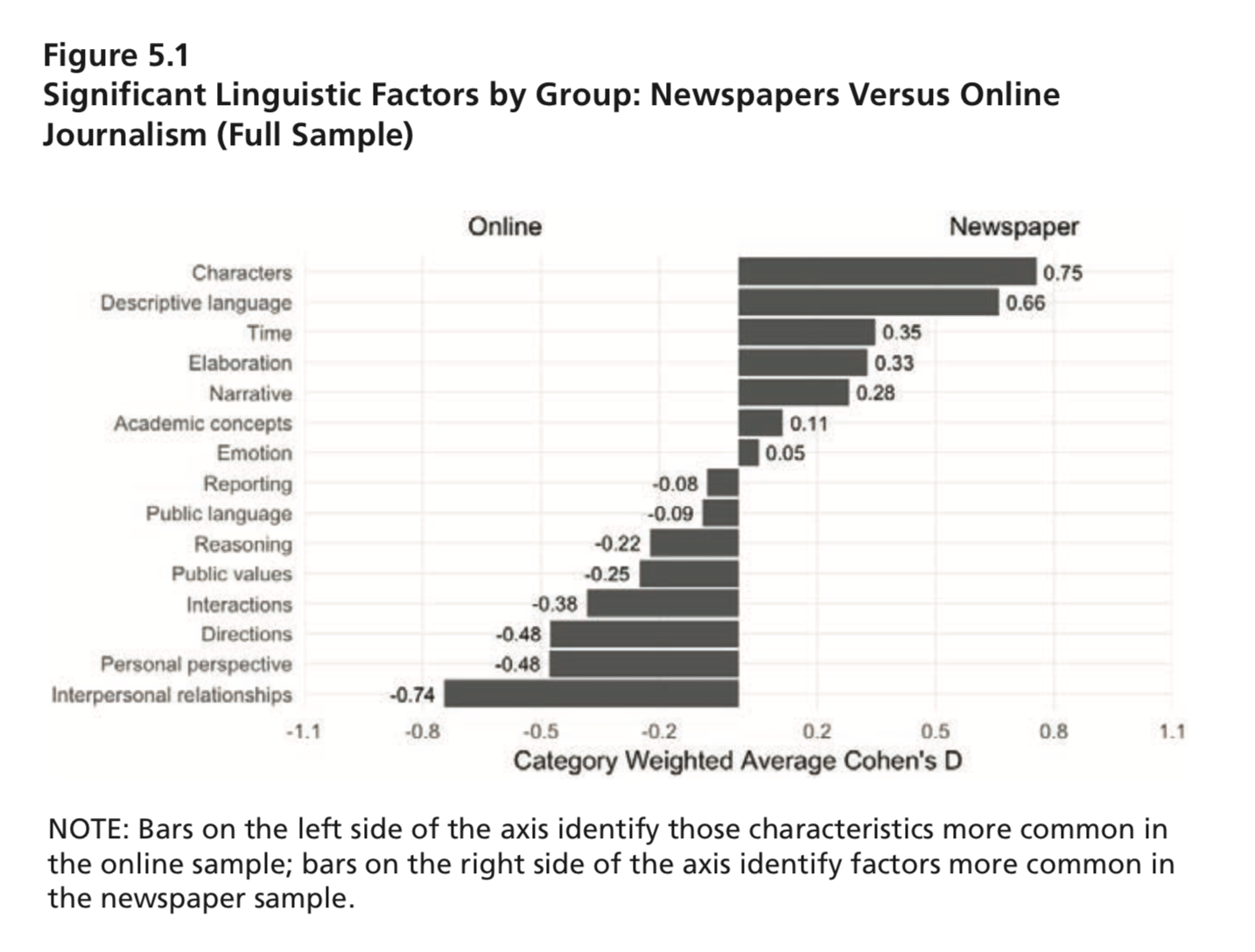

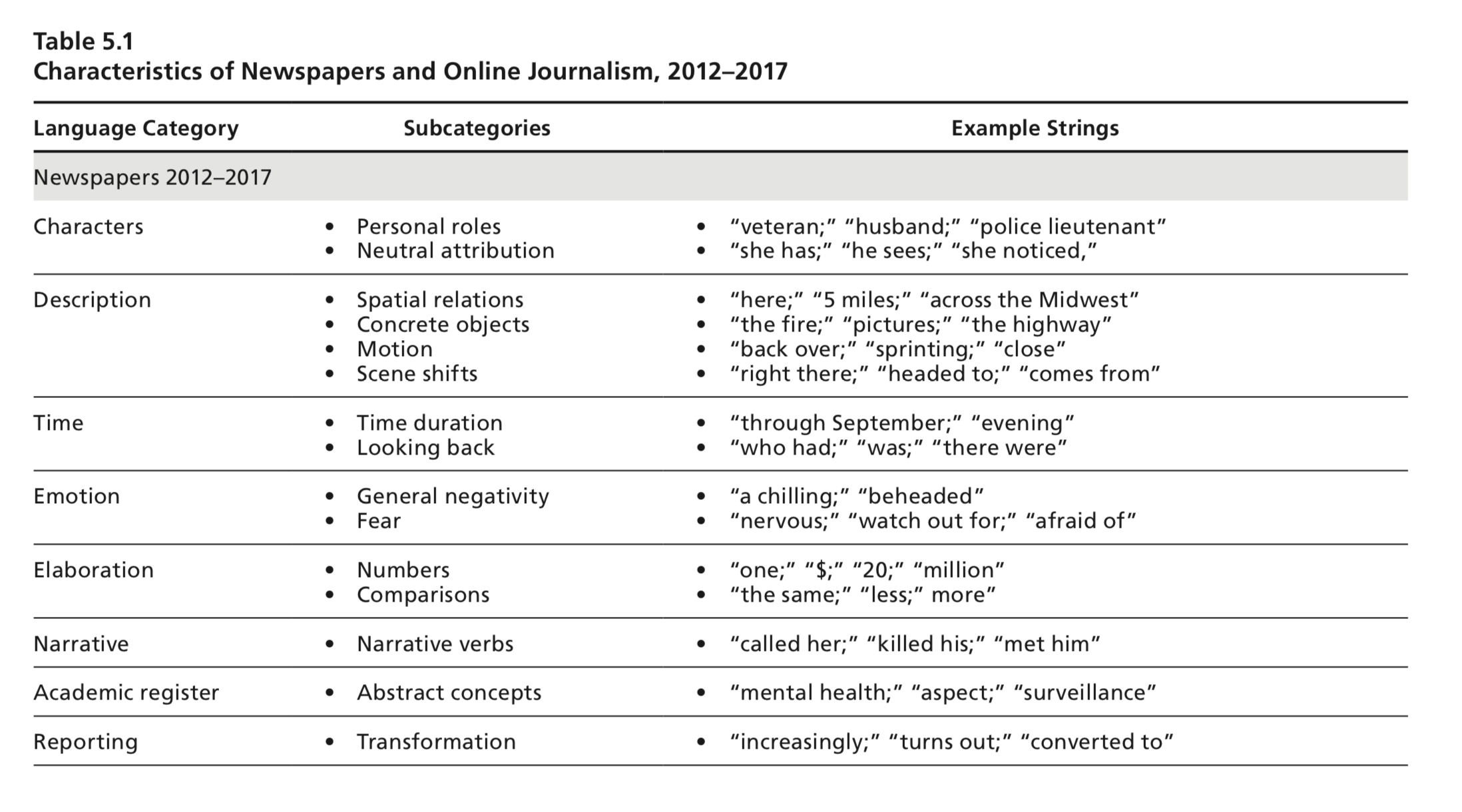

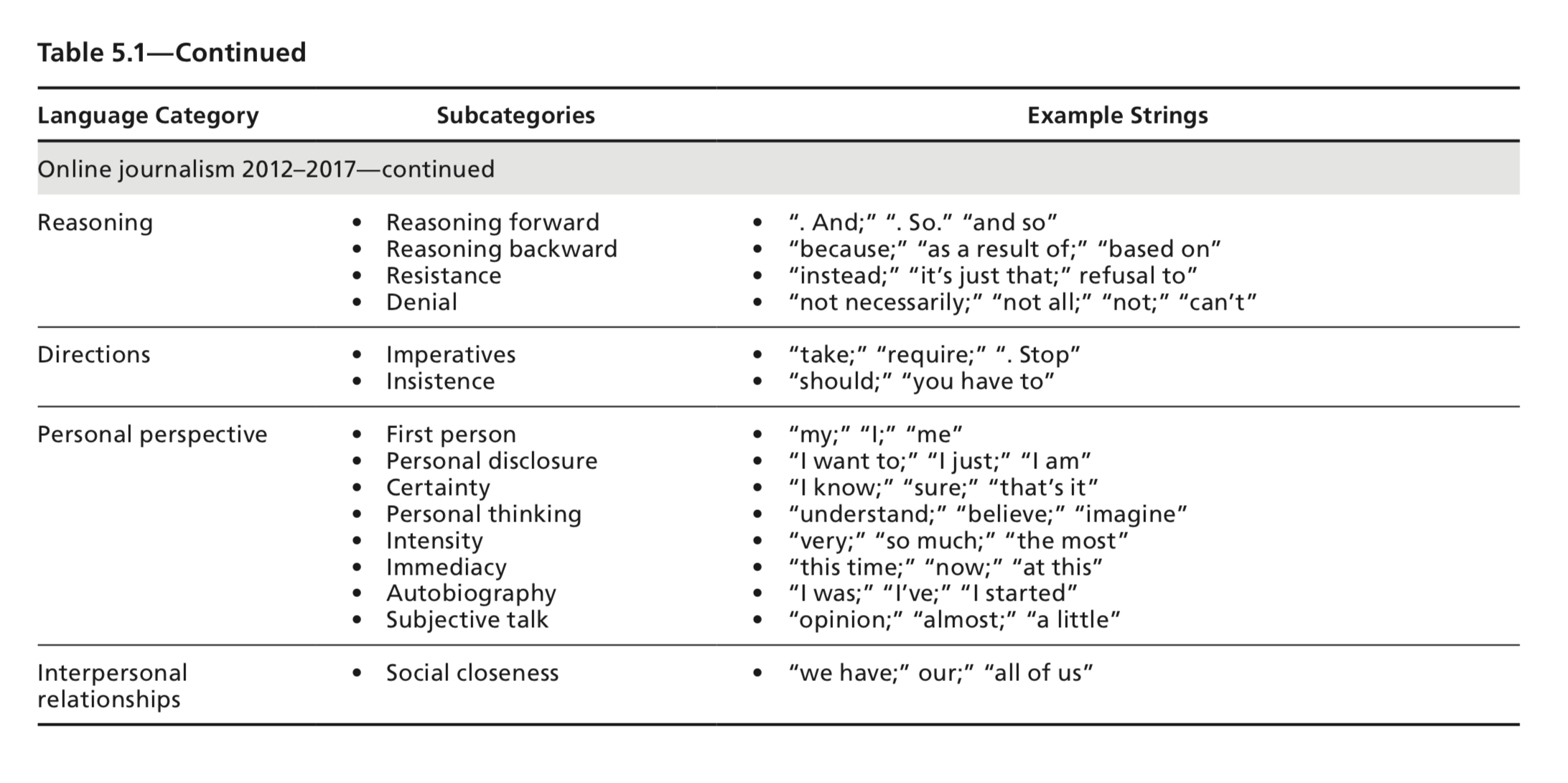

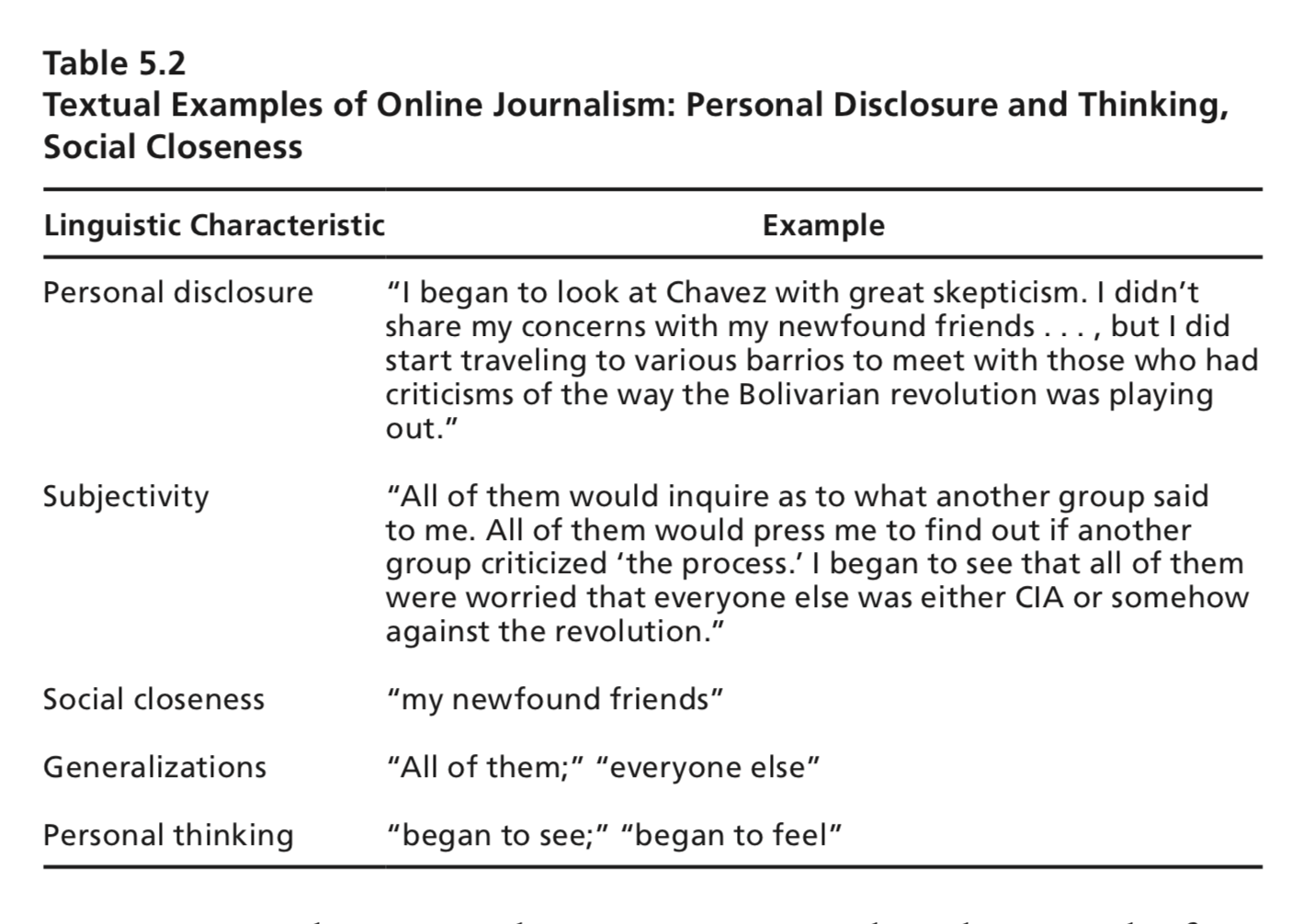

The final analysis in RAND’s report compares print journalism and online-only journalism between 2012 and 2017. As mentioned above, the outlets that it looked at were digital-only news sites BuzzFeed, Politico, The Huffington Post, Breitbart, Daily Caller, and The Blaze. The authors acknowledge that their research here is only a starting point; online news is much younger and harder to encapsulate, and they caution that their findings are “a first cut only.”

Compared with the newspaper journalism sample, the online journalism in our sample of highly trafficked sites is more personal and subjective, more interactive, and more focused on arguing for specific positions. Our online journalism sample is more strongly characterized by the use of directive language (sometimes of advocacy), references to personal interactions or interpersonal relationships, a strong personal presence, references to public values and authorities, and references to self. The result is a journalism that remains heavily anchored in key policy and social issues but that reports on these issues through personal frames and experiences — for example, analysis of the health care costs of opioid addiction through first-person narratives or analysis of proposed policy changes through the use of personal experiences and anecdotes.

As you might expect, the more intimate online space prompts more language of connection, social closeness, and subjectivity, while newspapers lean more into sensory-driven information — actions, spatial relationships, material objects.

There’s much more detail in the full report. For example, online news over-indexes on linguistic features the authors label as Metadiscourse, Anger, Confirming Opinions, Attention Grab, Curiosity, Insistence, and First Person. Newspapers are higher on Neutral Attribution, Looking Back, Numbers, Scene Shifts, and Transformation.

So yes, the authors conclude, journalism does appear to have become more subjective over time. But it still very much depends on the type of journalism you’re looking at. Newspaper reporting remains much as it was before the web — but both TV and online news rely more heavily on emotion, personal experiences, and argument.