Cari Wade Gervin had a story that needed to be reported, and nobody else was going to do it.

After two decades working in journalism, she had lost her job at a Tennessee alt-weekly in 2018 and turned to freelancing. She had found a story that involved the office of the state’s speaker of the house apparently faking an email in order to get the bond of an activist (who’d been arrested for protesting) suspended. “I pitched it, and no one wanted the story. I was like, ‘Well, I’ll just start a newsletter and send it out, because somebody needs to write about it.”

And so she did, in March, launching The Dog and Pony Show. Then she wrote about the governor’s staff using auto-deleting messaging apps to circumvent open records laws. Then she wrote about a married state representative who had voted against LGBTQ interests while using Grindr to meet up with younger men, leading to his resignation. That was the 15th issue of her newsletter (including several distributing the governor’s public schedule), five months after she’d started it, and now with almost a thousand subscribers.

In North Carolina, Tony Mecia was laid off from the conservative Weekly Standard when it shut down, and he too planned to return to freelancing — the same way he’d done it after taking a buyout at The Charlotte Observer a decade earlier. But then he considered the local business reporting scene and wondered how he could play a role. “I didn’t want to borrow or invest a bunch of money starting something up,” he said. So Mecia started sending out a newsletter three mornings a week — free, for now, to start — sharing a mix of original reporting and a scannable roundup. He’s at 1,600 signups after six months. “If it’s something you want to do, then don’t wring your hands,” he said.

Jack Craver highlights the Austin City Council’s happenings in his own newsletter in Texas; Shay Castle started sending out a newsletter about the activities of politicians in Boulder, Colorado after leaving the Daily Camera; and Adam Wren launched a newsletter alongside his freelance reporting on Indiana’s national political presence.

Inboxes are swelling with newsy email newsletters these days, and a lot of the industry dialogue centers on major national brands. (The New York Times in California, Wall Street Journal tweaks, Axios engagement, etc.) While places like The Atlantic, The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, and The New Yorker have all recently created roles specifically for developing their newsletter portfolios and purposes, the trend has taken off locally too — with a twist.

As revenue-starved local newsrooms shed journalists, some of them are using newsletters as a tool to build out their own one-person-show reporting operation — sometimes making money, but often using it to establish a brand presence while piecing together money from freelancing for national outlets, copywriting for corporations, or waiting tables on the side. There’s are any number of local, news-curating, email-driven startups as well (Whereby.Us, 6AM, Inside), but this model diverges by centering on the reporting work itself and turning to readers instead of advertisers for support in a bare bones reporter–reader relationship.

Newsletter companies like Substack and Revue have opened the tech-stack doors to building your own publishing system without relying on social media algorithms, and maybe even pulling in some personal subscription revenue. But they’re not perfect. Half of the journalists I interviewed for this piece use Substack, citing its ease with launch and payments; those not using it said they were either wary of how high the cut of revenue was (10 percent) or unaware that it existed (and had built their own Mailchimp/Stripe/Patreon integrations).

None of the six have been able to make a full-time living off of their local newsletter. But they’ve been able to cobble together an important service for their communities.

Holly Fletcher crunched the numbers on all this when she started her Nashville-focused newsletter on local healthcare and technology news.

“I was a trade reporter for five years covering power and utilities and the intersection with finance,” Fletcher, now a senior media strategist at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, said. “I was always exposed to very in-depth reporting as an object that someone was willing to pay for.” After working at The Tennessean for three years, she decided to run a little experiment with a local healthcare business newsletter she called BirdDog: “I wanted to know that there was still an audience for thoughtful reporting…and wanted to show that people still respected good information.”

Unlike Gervin and Mecia’s “just do it” approaches, she researched the business models and prospective audience, meeting with nearly 100 people to discuss what BirdDog could look like. She started out in March 2018 with the plan of three issues a week, but quickly realized that two issues were more realistic — and then scaled back even further to one quality email a week, on Sundays, to mirror the Sunday paper habit. Fletcher tested send times (a friend suggested trying an earlier sending time, but “me not being a morning person I thought that was crazy. I scheduled it for 3:30 a.m. and there was a whole group of people opening it before 5 and 6”) and formats (she included ads from two similarly minded entrepreneurs to test readers’ reaction to different designs) — but one of the biggest tests was the commitment created when money is involved.

“Whatever model you’re thinking about, the exchange of money means you owe someone something. You owe them a continuation,” Fletcher said. And she wasn’t sure if she wanted to continue, since she was enjoying the experimentation more than the grind — “I can assure you running a newsletter like that is a sun-up to sun-down job” — and she knew that keeping monetization, via sponsorship, investment, or reader revenue, out of the picture gave her an out. She stopping publishing six months after she launched BirdDog, ending with 1,600 subscribers. (She shared many more findings in her end-of-experiment post, including the newsletter’s 30 to 40 percent open rate and the stat that only 3.9 percent of her reader survey respondents were satisfied with Tennessee’s existing journalism options.)

“If you’re looking to sustain yourself, then you really have to work backwards, and say if I need X amount of money a year, what is that going to be per month, and how many people do I need to pay, or commit X number of months to get me to that number per year. Once you start doing these numbers, a lot of people are going to realize it takes scale,” Fletcher said.

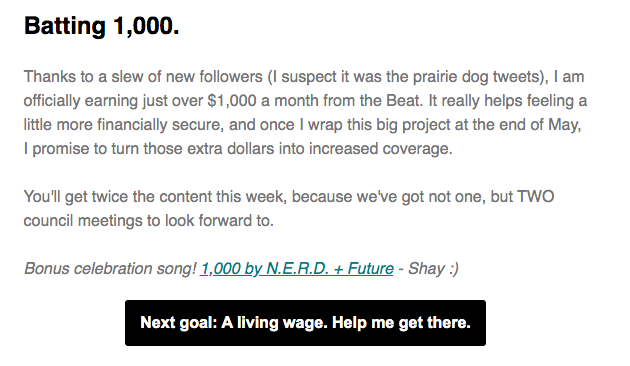

In Boulder, Shay Castle started Boulder Beat (both a site and a newsletter) after leaving the Daily Camera in January and has to remind her 700 readers that she’s doing this for them, and for free. “I believe news should be free and I believe people should pay for news. It’s like any public good or service. Not everybody can afford it — I can’t afford it,” she said. “Boulder is so freaking wealthy and some people can afford to pay. I’ve told my followers straight up: I did a check-in [in September] and I said ‘I’ve made less than $7,000 this year, so if you want to pay me [via Patreon or mail], you can.'”

She also laid it out for her email subscribers to pay attention:

There are other options. Perhaps acquisition, like how Pittsburgh writer Adam Shuck started a local news roundup email in 2014 that recently moved its 9,000 subscribers to Postindustrial Media, rebranding as The Pittsburgh Record. Or form a nonprofit to open up funding options: Tasneem Raja recently secured 501(c)(3) status for her Texas startup The Tyler Loop, which began as a full-blown website in 2017, though she has said she would’ve rather started it as just a newsletter if she did it again.

The subscriber-supported model is not impossible — just a bit tricky. (What, reader, in media these days isn’t?) Adam Wren, writer of Importantville in Indiana, seems closest to making his newsletter solvent — but that’s in part because it’s coupled with his national profile as a contributing editor to Politico Magazine and Indianapolis Monthly. He bills his Substack newsletter as “your indispensable guide to the intersection of Indiana politics, business, and power in the Trump era — and beyond.” After all, the vice president is the state’s former governor, the mayor of the state’s fourth-largest city is earning a high profile in the Democratic race, and there are powerful Hoosiers scattered throughout the administration and Congress. As Wren explained to me: “I found myself as a longform writer with bits and scooplets that I can’t use elsewhere. I should be able to find a way to put them to use, and maybe even monetize them as a freelancer.”

Wren took a local focus but put it on a national scale, with a Politico Playbook style. He’s been writing Importantville since April 2018, but switched from Tinyletter to Substack in June. Wren brought in 600 free subscribers in its first six months on Substack, sending emails two or three times per week. Now he sells subscriptions at $10/month or $100/year — using some proceeds to travel to D.C., Iowa, or New Hampshire, with about 10 percent of his 2,000-3,000 subscribers paying. Everyone gets a newsletter on Mondays with about a 50 percent open rate, but his paid subscribers get at least one extra newsletter per week, with about 70 percent opening. (Familiar to Nieman Lab readers as the Hot Pod model.) Most people in his audience are either connected to the political world or tech workers and young professionals based in Indianapolis — along with some Pete Buttigieg fans across the country. People can forward the newsletter at no charge, sure, but at least one scoop was shared around so much that it brought him 14 new paid subscribers in one day, Wren said.

“For me, it’s still a side hustle,” he said, though landing in inboxes more frequently does remind his sources to stay in touch. “I may only publish six to ten stories [as a freelancer] a year. The newsletter gives me an outlet to cover more stories incrementally and at a faster pace.”

The development of Importantville as a newsletter brand has now expanded into Importantville events, like a debate preview with Indy native and debate-prep expert Ron Klain and a forum with Senator Todd Young and former Rep. Christina Hale. And Wren is now working with a New Hampshire politics newsletter writer just starting out, trading dispatches and promos as Steven Porter tracks the first-in-the-nation primary’s developments.

But Wren still feels the same pressure Fletcher outlined: “Each time I get a new subscriber, it’s like I’m going to be doing this for another year to make sure I’m meeting people’s expectations,” he said. “You have to do it for at least two years to see if it really is going to find an audience.”

Wren’s newsletter has gained a national profile, with network bookers following his scoops. But the relationships between newsletter journalists and existing local media can be just as important as the ones between writers and readers. Mecia, in Charlotte, has gained exposure for his newsletter by appearing on the local NPR station every week, connecting with the moderator of a 35,000-member local Facebook group to share news, and even having established media like the Observer credit his original reporting when they follow up on it.

In Austin, Craver started his daily newsletter to build on his expertise covering the city council for the nonprofit Austin Monitor as a freelancer. He now only covers city hall for his Austin Politics newsletter — “after nine months, it’s a decent part-time job” — and meets up with as many of his subscribers as possible when they first sign up. “I remember meeting up with somebody who had recently subscribed to the newsletter and I said, ‘Thanks, I appreciate your support,’ and she corrected me and said, ‘I’m not being generous. I believe it adds value and it’s a product. I’m buying it,'” Craver said.

He has 230 fully paying subscribers at the same rate as Wren’s, who have the option to convert after a free trial period. Craver purposely avoided the grant-seeking nonprofit track, concerned about conflicts of interest: With subscriptions, he notes, “nobody can give me more than $10.”

Austin Politics is one of his babies; the other is his literal human baby who arrived six months ago. “I didn’t even take a break during that. I did some newsletters in advance,” Craver said. “I did take one week off around the Fourth of July, which everybody seemed cool with.”

Taking a break when you need to, having someone who can cover your beat when you do: These are important elements that are easier to handle in a traditional newsroom than in the freestyling local-newsletter-journalist life.

“This is more than 40 hours a week for far less than minimum wage. To be frank, it’s exhausting. I only do it because it’s so important,” Boulder Beat’s Castle told me hours after a city council meeting had wrapped up around midnight. “It’s weird being the only voice, the only one. You have no backup.”

“Once you get momentum, you’re kind of locked in,” Mecia of The Charlotte Ledger said. “If there’s days I’m out of town or with my kids, I don’t want to let readers down.”

“I would not recommend starting a local news subscription newsletter if you don’t have contacts in the news field that you feel like you can reach out to about the ethics of running something,” said Gervin, the Tennessee journalist whose reporting led to a state rep’s resignation. “It’s good to have a sounding board whose judgment you trust, where you can send them a text and say, ‘I think this is a great story, but I’m kind of worried.'”

With no decades-old news brand to stand behind, Gervin has also faced questions about her legitimacy as a reporter. “The hardest part of all this for me has been just trying to convince some people who are like, ‘Oh, you’re a freelance journalist doing this on your own, what even is your blog, you’re not even a real reporter.'” After the governor’s staff decided to remove her from their press email list, Gervin invited her readers to send a few emails of their own:

There are around one thousand of you lovely subscribers now (!!!), and maybe your influence will help remind the communications staff that the governor’s office is not a private business and doesn’t get to pick and choose which reporters it responds to.

And at least one, who Gervin said she didn’t know personally, did; she shared the email with me on his permission:

I’m writing to encourage you to reinstate Cari Wade Gervin on the Governor’s press list.

I grew up reading the Tennessean in print every morning. At first, it was just sports (Joe Biddle, Larry Woody & Jim Wyatt are names I can never forget), and then as I got older, I read the paper’s comprehensive coverage of Nashville and Tennessee. It’s been sad to see the lack of investment in what was once a great paper.

It’s incredibly challenging to be an informed citizen in today’s media environment. Media companies only provide coverage on events that are significant to the national conversation, because that’s the only way they can make money in the digital era.

Unfortunately, local journalism has not yet found a sustainable business model. I’m intrigued by the work Cari has done so far — and very intrigued by the business model opportunities powered by the newsletter/substack model.

Our politics need to be driven by a local dialogue, and that only occurs when we have local journalists that can make a living off of covering local issues. I’m sure I don’t have to tell you about Cari’s deep journalism experience at organizations in Nashville and the region.

That’s why the exclusion of Cari is so troubling to me. In the face of the nationalization of politics and the slow death of local newspapers, the Governor’s office is going out of its way to exclude those trying to power a new business model.

I hope the Governor recognizes the importance of local journalism and does not continue to stymie those that are trying to provide coverage on issues important to the state.