There are certain kinds of news stories that are really just iterations of an Ur-text, the defining statement about human existence that underlines a million variant tales. For instance, how many environmental stories do you read that are versions of Human activity is warming the earth’s atmosphere and damaging countless natural processes? Or how many political stories that all come down to Donald Trump lacks the standard human shame that limits how much people lie in public and obvious ways? There’s more news breaking every day — but at its core, it’s all just variations on a theme.

In the Nieman Lab universe, one of the core Ur-texts — alongside You’re probably going to need a paywall to survive, Information inequality is increasing, and There aren’t enough philanthropists to pay for all of local news — is Perceptions of the news media in the United States are radically and increasingly polarized by ideology. We’ve written about a gazillion studies, reports, and papers that reach a version of that conclusion. And here’s another one, with an international twist.

More in Common — a group that tries to “counter polarization” and “build bridges across dividing lines” — has a new report out this morning called “The New Normal,” which looks at “the impacts of COVID-19 on trust, social cohesion, democracy and expectations for an uncertain future.” It looks at seven countries (U.S., U.K., France, Germany, Italy, Poland, and the Netherlands) and is based on surveys of about 14,000 people.

There’s plenty of interesting non-media-focused data in there. (Like: “Many feel that COVID-19 has changed us into more caring societies, although the experience of COVID-19 in the U.S. is different — reflecting deep polarization, anxiety for the future and dismay at the Administration’s mismanagement.”) But for our purposes here, we’re interested in how perceptions of the news media have changed during the pandemic.

First, how does the media rank among various sources of information about COVID in terms of how trustworthy they are as providers of reliable information? Across countries, the answer is…not so bad. News organizations finish behind “your relatives and friends,” “experts from science and medicine,” and “your personal doctor” as reliable sources. (And, in Poland, the Pope!) But it ranks ahead of social media, local and national governments, business and union leaders, and, um, “influencers.”

(It’s worth noting that, while your relatives and friends have likely earned a high degree of your personal trust in many ways, they are not on average any more likely to have accurate information than a random person off the street. That your uncle loves you doesn’t mean he has sound thoughts on mask-wearing.)

Across countries, though, people were also asked if they agreed with this statement: “The media seem to be pursuing their own agenda rather than simply reporting the facts.” With the exception of Germany (49 percent), a majority of each country said yes, including 60 percent in the U.S. and 75 percent in the U.K. Those are higher figures than other questions that focused on analogous malfeasance on the part of governments.

(Not to be picky here — it’s a hard question to get right — but “simply reporting the facts” is an artificially high bar of neutrality to set in many ways. All news outlets, even the most down-the-middle wire services, make editorial choices about what facts to report — and then put those facts in some sort of context or provide some level of analysis. Perhaps something like “…rather than reporting without bias” or “…rather than presenting information in a neutral manner” would change the results a bit.)

But the most interesting part of this study — the one that summons up the underlying Ur-text — is the comparisons across countries.

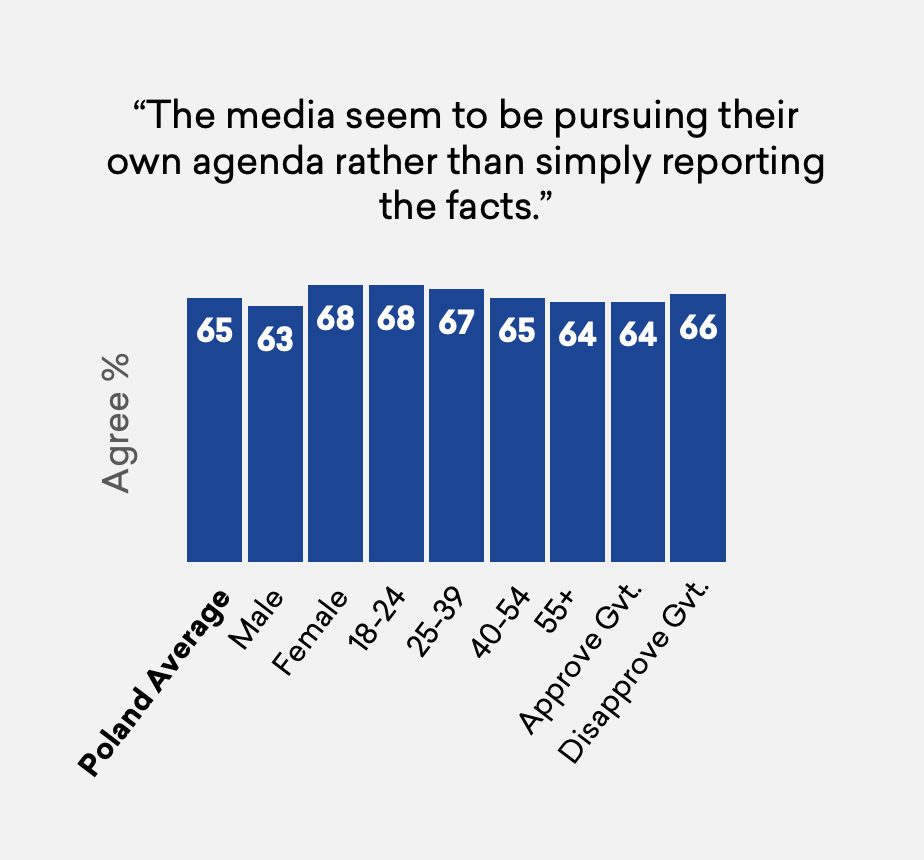

More in Common has modeled the political clusters within several (though not all) of these countries, combining left-right position on the ideological spectrum with other factors like class, education, and political interest. In the countries without those defined clusters, More in Common uses demographic information (age, sex, region, education) or support/opposition to the incumbent government to divvy up respondents. Watch for how similar or different each country’s various groups are in their trust in the media.

In Poland, views of the media are almost identical across men and women, age groups — and even support or opposition to the incumbent conservative government, whose support from the national public broadcaster was controversial in this year’s election.

The same is true in the Netherlands, where no demographic group strayed more than 5 percentage points from the national average.

As well as in Italy — everyone is tightly clustered around 65 percent.

But what about the countries where More in Common has identified specific political clusters? It stands to reason that those clusters — more multifaceted and more numerous than simple demographic bands — might have wider variance in their opinions about the media.

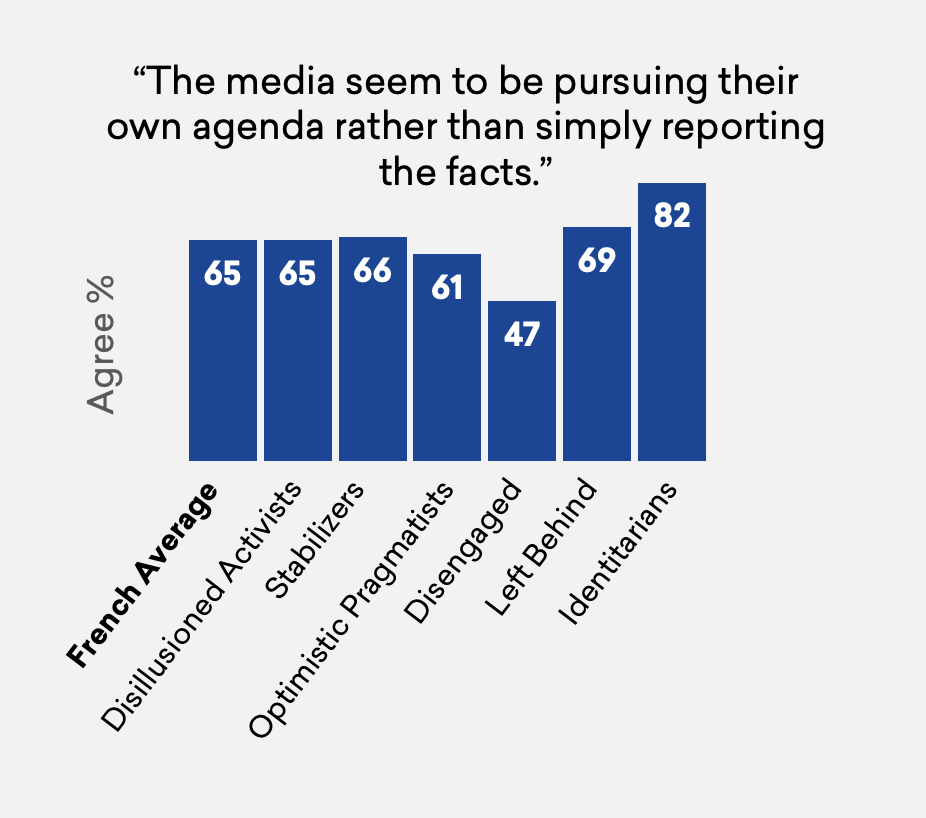

Here’s France, which More in Common divides into these groups:

Disillusioned Activists (12 percent of the national total): educated, cosmopolitan, progressive, not religious, pessimisticStabilizers (19 percent): moderate, engaged and established, participating in civic life, rational, compassionate, hold mixed opinions

Optimistic Pragmatists (11 percent): young, individualistic, pragmatic, confident, entrepreneurial

Disengaged (16 percent): young, detached, lacking confidence, individualistic

Left Behind (22 percent): angry, defiant, feel abandoned

Identitarians (20 percent): older, conservative, nativist, uncompromising, believe in national decline

It’s hard to map these onto American politics, but you might think of these groups as stretching from Elizabeth Warren voters (Disillusioned Activists) to Donald Trump voters (Identitarians). Or in France, perhaps from Jean-Luc Mélenchon to Marine Le Pen.

Here’s how these groups break down on the media:

There is more variation here than in the demographics-only countries — but the range is still not epic. The leftmost group is right at the national average, the rightmost group is only 17 points higher, and the lowest result comes from people who are disengaged from the political process.

Here’s Germany, where More in Common’s cluster analysis breaks down like this:

The Open (16 percent) value self-expression, open-mindedness and critical thinkingThe Involved (17 percent) are civic-minded and active democrats, value togetherness, and are willing to defend progressive social achievements

The Established (17 percent) value reliability and social harmony and are most likely to feel satisfied with the status quo

The Detached (16 percent) value success and personal advancement, are less likely to think in abstract societal terms or to be interested in politics

The Disillusioned (14 percent) have lost a sense of community and long for recognition and social justice

The Angry (19 percent) value order and control in national life, are angry at the system, and have very low levels of trust

These clusters are heavier on values and psychology than France’s; in More in Common’s analyses on other German issues, The Established and The Involved often sit on one end of the spectrum, with The Disillusioned, The Angry, and The Detached on the other.

Here’s how these groups look on media:

Here we have our first real outlier: The Angry is a full 31 points ahead of the national average in suspecting the media of pressing its own agenda. But otherwise, every group is within 11 points of the average. The Established and The Detached are virtually identical, not on opposite ends.

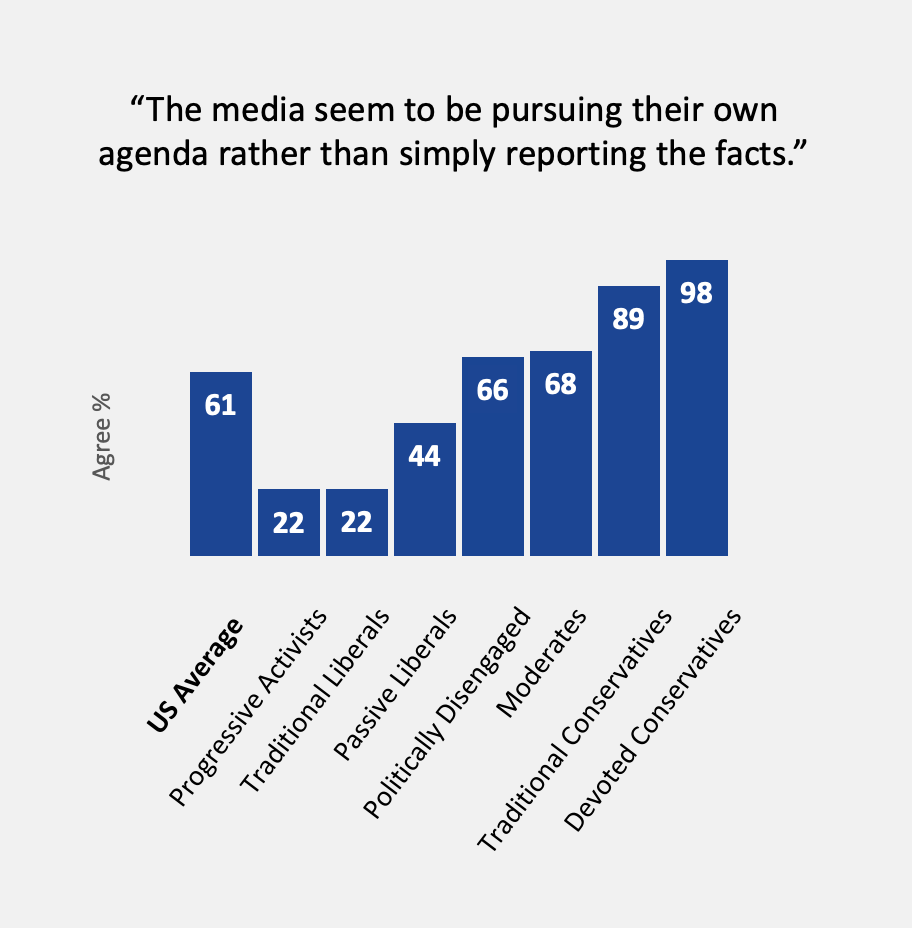

Okay — all of that is a leadup to the United States. It’s important to see how relatively similar different groups are on their evaluations of the media in these other countries. More in Common’s analysis divides Americans into these clusters:

Progressive Activists (8 percent): younger, highly engaged, secular, cosmopolitan, angry. Main concerns: climate change, inequality, poverty.Traditional Liberals (11 percent): older, retired, open to compromise, rational, cautious. Main concerns: leadership and division in society.

Passive Liberals (15 percent): unhappy, insecure, distrustful, disillusioned. Main concerns: healthcare, racism, poverty.

Politically Disengaged (26 percent): young, low income, distrustful, detached, patriotic, conspiratorial. Main concerns: gun violence, jobs/economy, terrorism.

Moderates (15 percent): engaged, civic-minded, middle-of-the-road, pessimistic, Protestant. Main concerns: division, foreign tensions, healthcare.

Traditional Conservatives (19 percent): religious, middle class, patriotic, moralistic. Main concerns: foreign tensions, jobs, terrorism.

Devoted Conservatives (6 percent): white, retired, highly engaged, uncompromising, patriotic. Main concerns: immigration, terrorism, jobs/economy.

More in Common defines four middle groups — from Traditional Liberals to Moderates — as the “Exhausted Majority,” a group of Americans who are significantly less partisan and less politically active than those farther right and left. The Exhausted Majority is “considerably more ideologically flexible” and tends “to deviate significantly in their views from issue to issue.” (Personally, I’d define the Exhausted Majority more narrowly — just Passive Liberals and Politically Disengaged — because those two groups turn out to vote at much lower levels than the other five.)

If I had to come up with politicians who best represent each of those segments, I’d probably say:

Progressive Activists: Bernie Sanders, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Ayanna Pressley, Barbara Lee

Traditional Liberals: Joe Biden, Barack Obama, Nancy Pelosi, Chuck Schumer

Passive Liberals: no one, but they don’t like Donald Trump

Politically Disengaged: no one, although they often liked both Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump in 2016

Moderates: John Kasich, Joe Manchin, Susan Collins, Charlie Baker

Traditional Conservatives: Mitt Romney, George W. Bush, Ben Sasse, Marco Rubio

Devoted Conservatives: Donald Trump, Tom Cotton, Ted Cruz, Ron DeSantis, primetime Fox News

So, how do these different groups view the media? Wildly differently.

Look at that range!

Two middle groups — the Politically Disengaged and Moderates — look a lot like people in the study’s European countries. But on both ideological ends, trust in the news media is almost completely tied to your political beliefs. A whopping 98 percent for Devoted Conservatives versus just 22 percent for the two most liberal groups.

That 76-point gap is a profoundly American phenomenon.1 You just don’t find it in the other countries measured — even in places where the political mainstream has faced significant challenges from the populist right.

And when you have this wide of a perception gap in the motives of the news media, it’s not shocking that it sometimes feels like Americans live in two different information universes — one where Donald Trump is the worst president in American history, and one where he’s about to arrest hundreds of cannibal pedophile Democrats.