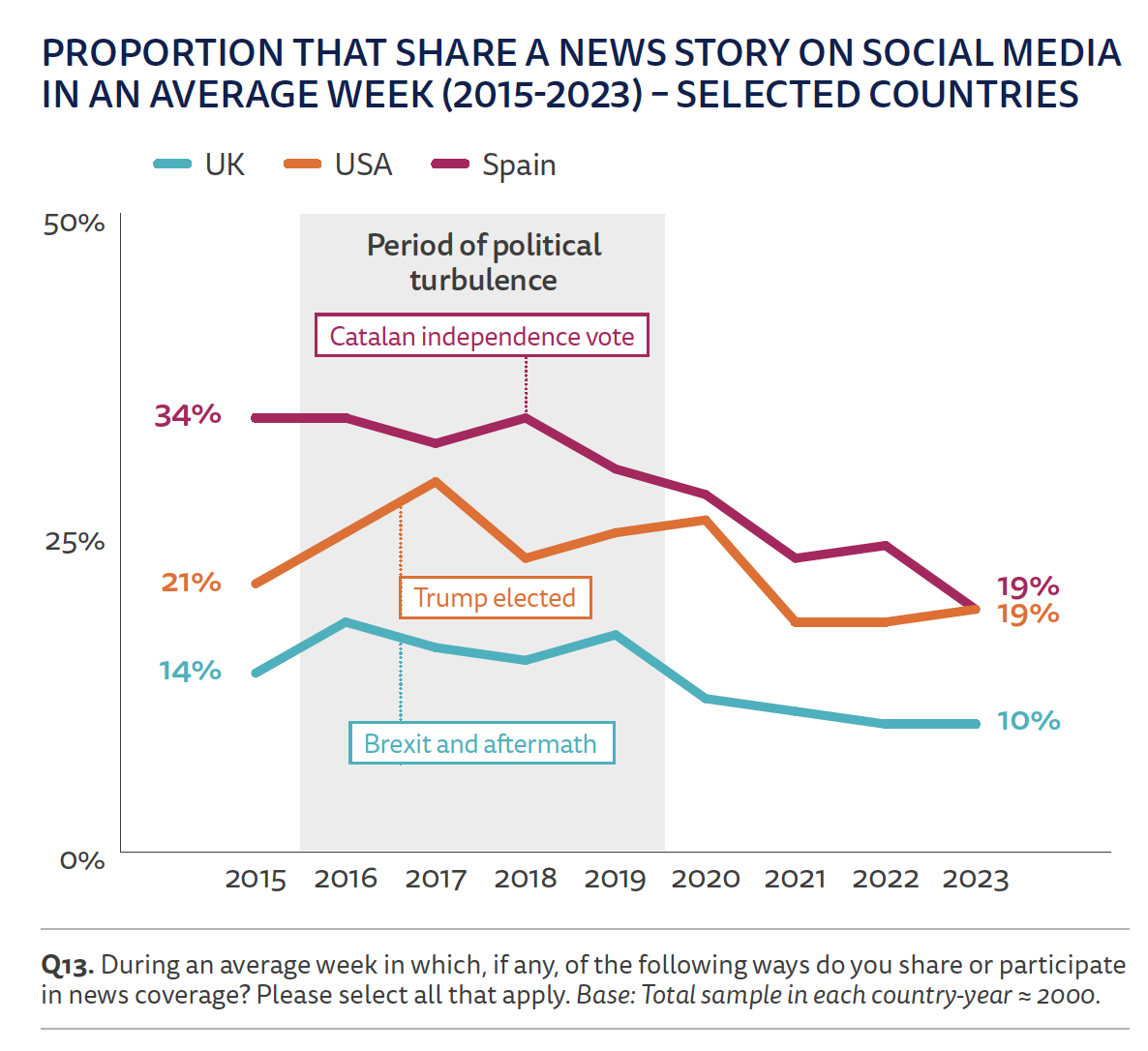

Facebook’s exit from news tracks tracks with a move toward TikTok and Youtube, and a worldwide decrease in commenting on and sharing news articles. That’s one of the findings from Oxford’s Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism (RISJ) in its 2023 Digital News Report, out this week.

RISJ has released a digital news report every year since 2012. This year it surveyed more than 90,000 people in 46 countries about their news consumption, via a YouGov survey as well as qualitative research about subscriptions in the U.S., U.K., and Germany. It’s a big, meaty report. Here are a few of the main findings. And stay tuned because we’ll be running two more pieces by RISJ researchers over the coming week — one on how audience thinking about news algorithms has evolved, and one about how news participation has changed.

In 2017, 63% of respondents across markets said they were “very or extremely” interested in news. This year, 48% said that.

A little over a third (36%) of respondents said they avoid news either “often” or “sometimes.” For the first time this year, RISJ tried to categorize the different ways that people avoid news:

[We] found that half of avoiders (53%) were trying to do so in a broad-brush or periodic way — for example, by turning off the radio when the news came on, or by scrolling past the news in social media. This group includes many younger people and those with lower levels of education.

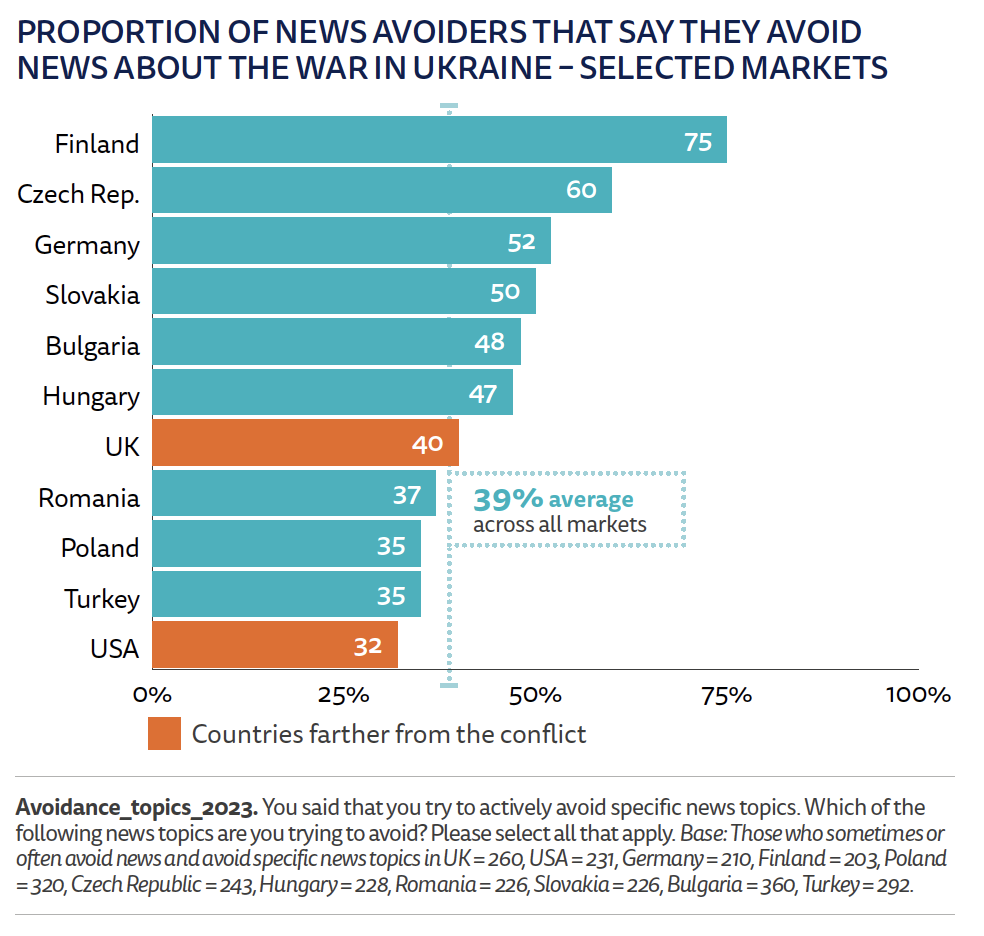

A second group tends to avoid news by taking more specific actions. This may involve checking the news less often (52% of avoiders), for example by turning off mobile notifications, or not checking the news last thing at night, or by avoiding certain news topics (32% of avoiders) such as the war in Ukraine or news about national politics…

Certain news stories that are repeated excessively or are felt to be “emotionally draining” are often passed over in favor of something more uplifting.

“Turning my back on news is the only way I feel I can cope sometimes,” a 42-year-old woman in the U.K. said. “I have to consciously make the effort to turn away for the sake of my own mental health.”

Avoidance of news about the war in Ukraine was particularly high in the countries closest to the conflict. RISJ notes that this “may not suggest a lack of interest in Ukraine from nearby countries but rather a desire to manage time or protect mental health from the very real horrors of war. It may also be that consumers in these countries already consider themselves to be well-enough informed on Ukraine, with extensive and detailed coverage across all channels, including via social media.”

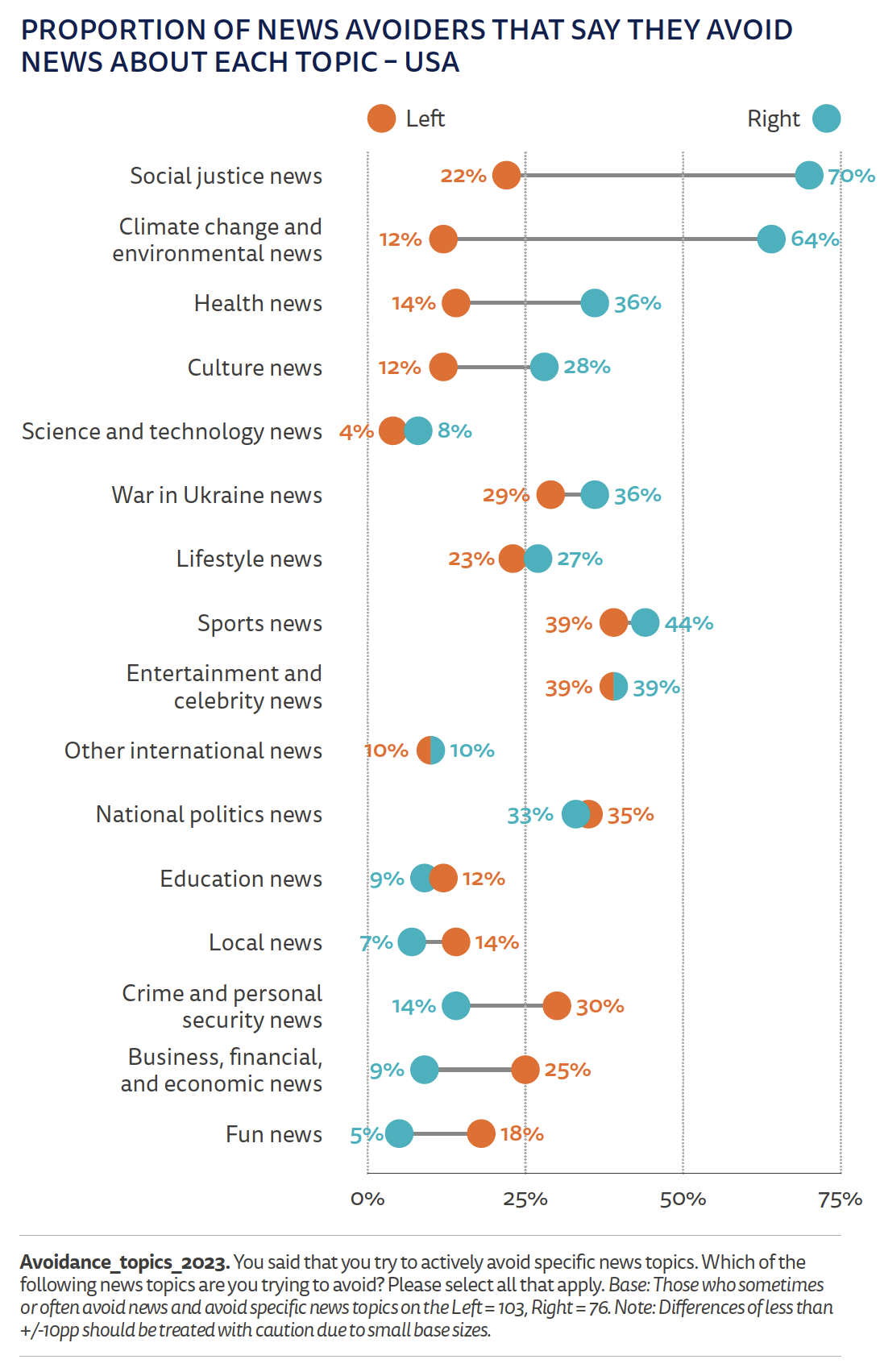

In the U.S. — a long way away from Ukraine — RISJ sees a different pattern of news avoidance: “We find that consumers are more likely to avoid subjects such as national politics and social justice, where debates over issues such as gender, sexuality, and race have become highly politicized.”

The report’s authors sum up the conundrum for publishers:

At a headline level, we find that avoiders are much less interested in the latest twists and turns of the big news stories of the day (35%), compared with those that never avoid (62%). This explains why stories like Ukraine or national politics perform well with news regulars but can at the same time turn less interested users away. Selective avoiders are less interested in all types of news than non-avoiders but in relative terms they do seem to be more interested in positive or solutions-based news. Having said that, it is not clear that audiences think much about publisher definitions of terms such as positive or solutions journalism. Rather we can interpret this as an oft-stated desire for the news to be a bit less depressing and a bit easier to understand.

Across 20 countries, RISJ found that 17% of people have paid for online news, the same as last year. A “winner takes most dynamic persists in many markets,” with big publications accounting for most subscriptions:

In the U.S., the number of Americans who pay for a subscription ticked up a bit, to 21%. The trend of Americans being willing to pay for more than one subscription continues. Most Americans who pay for news (56%) pay for two or more subscriptions, and RISJ says it has “started to see more second subscriptions in other markets including Australia, Spain, and France.”

Substacks remain a uniquely American trend, at least for now: In the U.S., 8% of people who subscribe to news “pay for a newsletter written by an individual journalist or influencer and 5% pay for a podcaster or YouTuber.”

RISJ also found “a large amount of underlying change, much of it driven by cost pressures.” From the report:

Around one in five news subscribers (23% on average) say they have canceled at least one of their ongoing news publications, while a similar number say they have negotiated a cheaper price…

According to our data, around half of subscribers are maintained subscribers, who are confident about value and are unlikely to churn. These tend to be older and less price-sensitive customers. But that leaves a significant proportion of price-sensitive subscribers who are shopping around for deals and regularly reassessing value. This suggests that churn is likely to be a major problem this year and beyond.

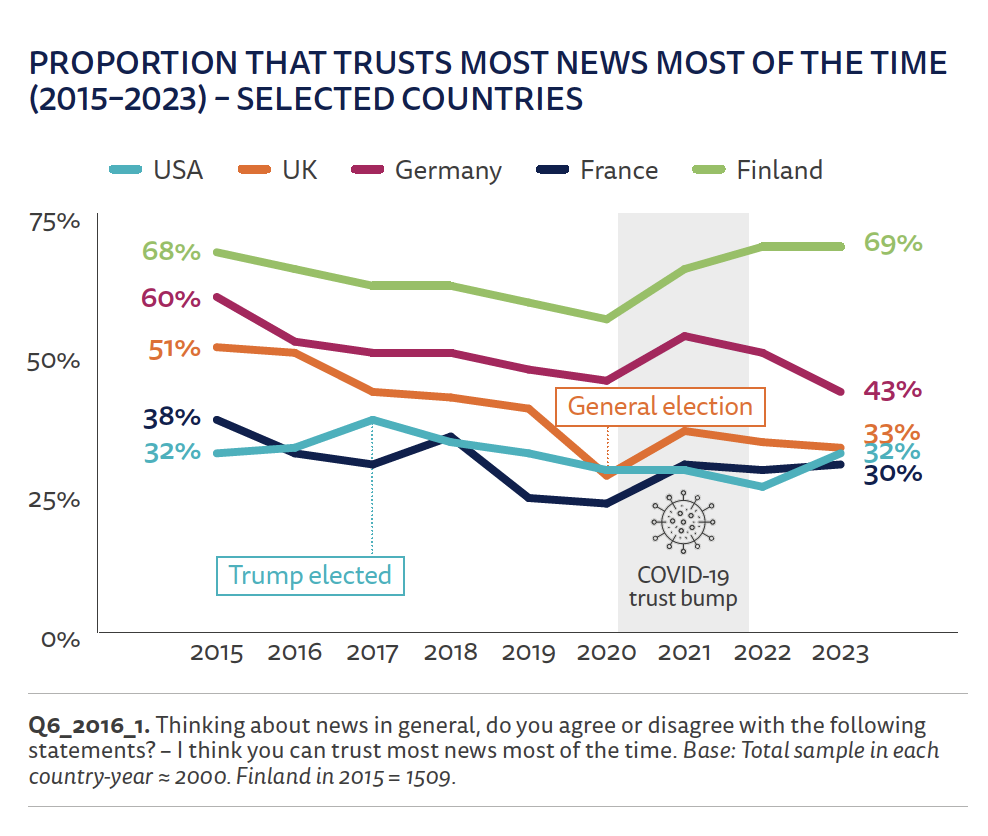

This year, though, 32% of Americans agreed with that statement (same as in 2015). This increase in trust is unusual among Western countries: In Belgium and Germany, for instance, stated trust in the media is down since last year.

The authors offer a useful reminder (that we’ve written about too): “These scores are aggregates of subjective opinions, not an objective measure of underlying trustworthiness, and changes are often at least as much about political and social factors as narrowly about the news itself.”

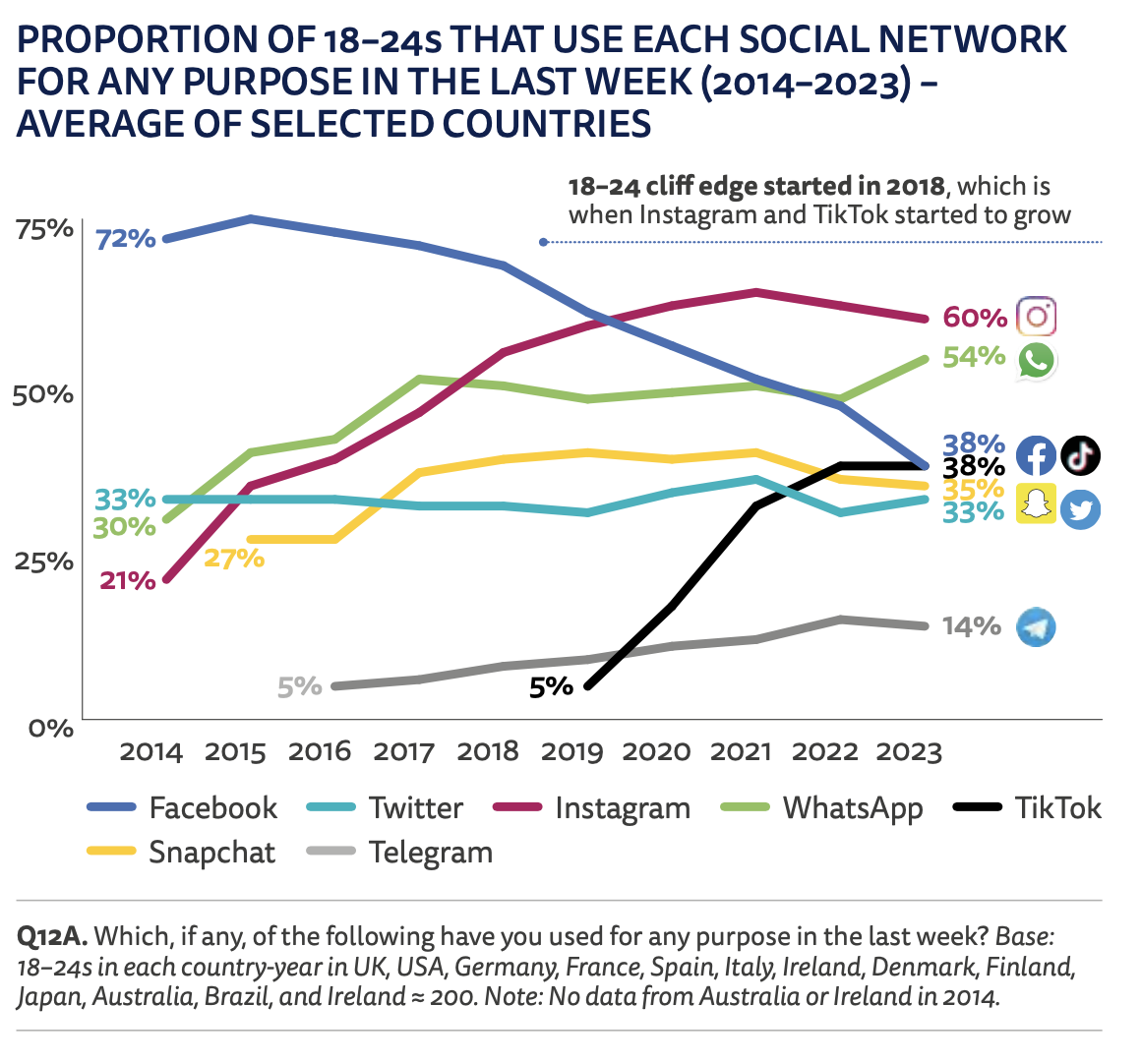

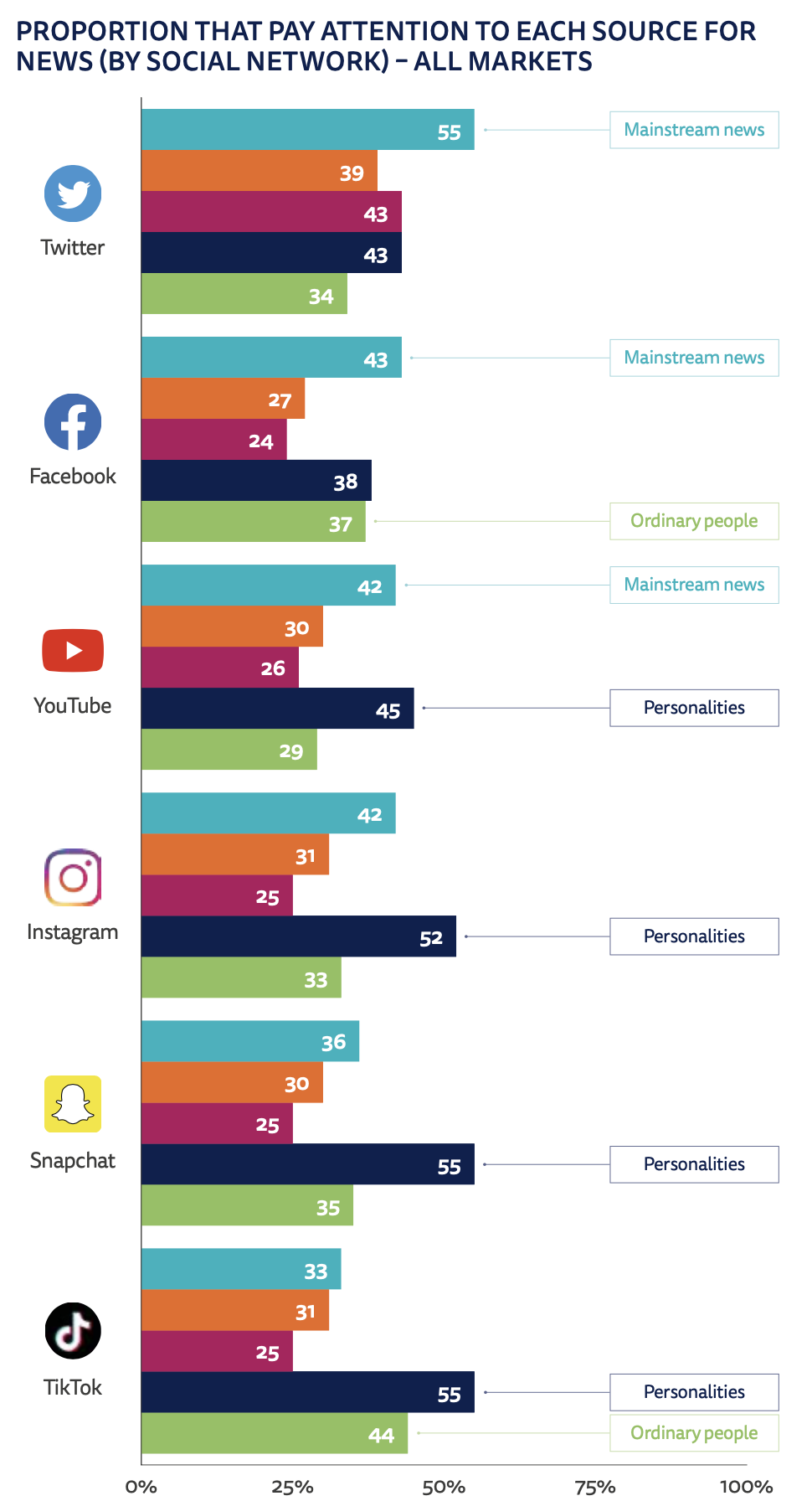

Worldwide, just 22% of respondents “say they prefer to start their news journeys with a website or app,” down 10 percentage points since 2018. For most, social has taken over as the first path to news. And the fastest growing social networks — TikTok, Instagram — focus on “celebrities, influencers, and social media personalities,” not on news organizations or journalists.

There’s much more in the full report, which you can read here.