This story originally ran at El Tímpano.

Like a virus, misinformation spreads by individual actions. Sharing a post on WhatsApp or Facebook, repeating a rumor in conversation with relatives or colleagues: These individual decisions have ripple effects through social circles, workplaces, and entire communities.

So when El Tímpano launched a disinformation defense initiative two years ago, we targeted individuals. Specifically, Latino immigrants — individuals who were (and are) themselves targeted by disinformation campaigns and experienced the rapid spread of dangerous falsehoods in their communities.

At the time, most disinformation defense initiatives relied on institutions such as a fact-checking site or social media platform to verify or debunk suspect information. But this centralized approach didn’t make sense for an organization designed with and for Latino and Mayan immigrants. For one thing, there was no way our small organization could verify or debunk every piece of disinformation circulating among our audience. But even if we had the bandwidth to do that, a fact-checking effort would be a game of whack-a-mole, consuming resources without making a long-term impact. We sought a more sustainable approach.

Our strategy, Comunidades Informadas (“informed communities” in Spanish) found inspiration in the promotoras model of public health education. This model, developed in Latin America and popularized in Latino immigrant communities in the U.S., recognizes that the word of a mother, a neighbor, or a community leader carries more weight in influencing behavior change than a traditional PR campaign, government agency, or other institution. As promotoras, community members themselves — already trusted messengers in their own social circles — are trained to be public health educators.

With Comunidades Informadas, our aim is similar: to decentralize disinformation defense by training our audience to identify disinformation and stop its spread in their communities.

To design a workshop, we sat down with disinformation experts and spent time reviewing existing resources on the tactics of disinformation and how to identify it. We also met with members of the local grassroots organization, Mujeres Unidas y Activas, and staff of the Oakland-based La Clínica de la Raza to create curriculum and discussion points that would resonate with the experiences of their members and patients.

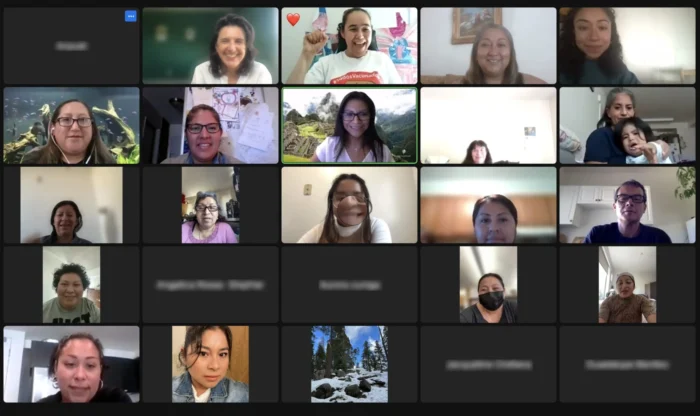

Since 2021, we’ve conducted our Spanish-language disinformation defense workshops online and over the phone with grassroots organizations, ESL classes, nonprofit staff, groups of seniors, and promotoras, and in person with parent leaders at local schools. In all, we’ve trained more than 100 community members on what disinformation is, how to identify it, and steps they can take to halt its spread. Thousands more have received our curriculum through a series of text messages that conveys key takeaways from the workshop.

In the process, we’ve learned a lot about how Latino immigrants experience dis- and misinformation, and what it takes to defend communities against its harms. As the 2024 election has brought about a new sense of urgency to address the issue, we want to share five lessons we’ve learned while doing this work.

Similarly, efforts to combat disinformation in Latino immigrant communities by creating Spanish-language versions of strategies developed by and for non-immigrants can miss the mark. Those approaches often neglect an understanding of the distinct reasons Latino immigrants are vulnerable to disinformation. It’s not because they’re simply duped; more likely, it’s because they lack a source of trusted information. Fact-checking from an organization they don’t know or trust won’t solve that issue.

Most of our workshops took place during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, when disinformation about the virus and the vaccines was running rampant.

But COVID-19 wasn’t the most common issue that workshop participants brought up. Neither was politics.

What was?

Consumer fraud.

People experience disinformation in myriad ways, and while electoral politics and vaccine misinformation have driven the media and researchers to focus on it, the fact is that immigrants have been targets of disinformation for decades from scammers who prey on vulnerabilities such as lack of fluency in English, financial instability, lack of health care, and fear of law enforcement. In every workshop, participants have shared examples of scams they’ve experienced — some online, some over the phone, others via mail or in person.

If our efforts only focused on combating public health or political disinformation, we would miss the opportunity to combat the most common forms of disinformation our community experiences. But because our workshop focuses less on specific pieces of disinformation and more on common tactics used and traits to identify it, participants are equipped to defend themselves against disinformation on any topic, from public health and politics, to their bills, online shopping, or anything else.

When community members realize they are tricked, scammed, or misinformed, it not only harms them in the moment, but has a prolonged effect on their confidence to make good decisions.

In one workshop, a participant shared that she “felt like a fool” after being scammed by a company that promised its pills would help with joint pain. After she bought them, the company continued to take money out of her account. Not only was she left with debt and pills that did nothing, but every time she felt joint pain, she was reminded of being scammed. “I should know better than to believe in a magic pill,” she said, “but the pain was so uncomfortable, I wanted a quick fix.”

She is one of many participants who recount feeling embarrassed, ashamed, and self-conscious after falling victim to disinformation. Such feelings can lead them to question their own judgment and make it harder to ask for and receive information in the longterm.

It’s one more reason popular education is a valuable strategy to combat disinformation: It creates a safe space for people to share their experiences, learn that they’re not alone, and strengthen their skills and confidence in assessing information moving forward.

In planning and facilitating our workshops, we’ve found partners in various places: schools, community health centers, parent groups, grassroots organizations, and nonprofit staff. What do they all have in common? They have experienced the deluge of disinformation firsthand and want to do something about it.

Sure, news outlets are in the business of informing our audiences, but everyone has a stake in being informed.

If your organization is planning a disinformation initiative, take some time to map out who in your community could be a valuable partner and collaborator. Ask:

Those questions may lead you to unexpected allies to support your efforts.

While El Tímpano’s disinformation defense workshops have been recommended enthusiastically by participants and partners, it is our ongoing Spanish-language news and information service that addresses a root cause of disinformation, particularly when it comes to immigrant communities: the lack of a trusted and reliable source of news.

Due to our workshops, more than 100 Latino immigrants have the tools and training to stop the spread of disinformation. But due to our ongoing text-messaging platform of news, information, and participatory reporting, thousands of immigrants across the Bay Area have a source they can trust.

Yes, if our subscribers share with us a suspect message they see on social media — and they do — we fact-check it. But more importantly, and more consistently, we provide them with verified news and information and answer their questions on timely issues, filling a void that could otherwise be filled by disinformation. One longtime subscriber, Abel, described to us the impact our news service had when COVID-19 vaccines were starting to be distributed and disinformation ran rampant:

I was one of those who, maybe because of not being well informed, was hesitant about the COVID-19 vaccine. But the information from El Tímpano was really valuable. You answered my questions, told me how to make an appointment, where to go, and what it involved. It was tremendously helpful.

In other words, the most powerful antidote to disinformation is information — trusted, accessible, and verified.

Madeleine Bair is founder of El Tímpano, where this piece originally ran. Thanks to Etel Calles for contributing and Claire Wardle for reviewing. The El Tímpano staff and contributors who have played a role in developing Comunidades Informadas include Diana Montaño, Wen Calm, tania quintana, and Etel Calles.