Editor’s note: On April 23, Nicco Mele’s new book The End of Big: How the Internet Makes David the New Goliath will be released.

Editor’s note: On April 23, Nicco Mele’s new book The End of Big: How the Internet Makes David the New Goliath will be released.

Nicco — a lecturer at the Harvard Kennedy School, a political and digital strategist, and the Internet operations director for Howard Dean’s 2004 presidential race — argues that digital technology empowers individuals over organizations and that the companies that succeed going forward will be those who embrace that trend.

(You can see Nicco discuss the issue with Clay Shirky here.)

Here, he — with Kennedy School colleague and Nieman Lab contributor John Wihbey — makes the argument for a new, networked journalism that serves as a platform for talent.

The data behind Pew’s State of the News Media 2013 are the latest terrifying signs of the decline of the news industry. With three of America’s most esteemed papers for sale — The Boston Globe, the Chicago Tribune, and the Los Angeles Times — it’s time for a reboot to the fundamental business model for news. News revenue remains overwhelmingly dependent upon advertising, but the radical connectivity of the Internet has greatly diminished both the scale of newspapers’ reach as well as the value of advertising. John Wanamaker famously observed, “Half the money I spend on advertising is wasted; the trouble is I don’t know which half.” It turns out it is not a matter of which half your advertising is successful; it’s a matter of which one percent is successful.

But same digital dynamics that have created a crisis also offer an emerging and still under-appreciated set of solutions. For all the talk about the importance of social media, it is striking that few news organizations have thought to leverage the people and personalities inside them in a bold, strategic way.

What if journalists became like your doctor, dentist, or teacher — people who provide a valuable service to you, and whose name, voice, and personality are more intimate? The question then becomes how to create a social presentation layer that wraps around news — preserving the integrity of the product but updating its interface to fit with human behavior in the digital age.

The rich, wonderful, but also deadly combination of aggregators, blogs, newly ingrained information-seeking habits, and social media streams has destroyed the idea of brand recognition or audience loyalty around a masthead or single news “entity” (a few exceptions notwithstanding). Without an identity, much journalistic content will increasingly be swept around the Internet in an anonymous blur of sharing and finding through networks, with little regard for the source or the labors taken to produce that news. Many legacy news outlets have, in the Internet world, become a bunch of increasingly empty, faceless brands invoking ancient words like “tribune” or “herald” or “gazette.” What are these weird archaic cults? the public wonders. What strange medieval guilds still work at them?

At the same time, technology radically empowers individuals. Institutions are rarely successful on social media; it is a profoundly intimate medium that is for individual persons, and as such opens up new opportunities for journalism.

Future success requires deploying reporters and editors in ways commensurate with the radical shift in digital technology itself. That’s why the new potential owners of the Globe, Tribune, and Times might be well served to consider a wholly different way of thinking about their purpose and operations: re-design the newspaper to be a platform for talent across multiple media.

A key advantage of organizing around talent — reimagining the news organization as a platform for outstanding individuals — is that it opens new revenue opportunities. A principal problem of the news organization online is that the existing models are still too advertising centric, and advertising doesn’t pay the bills online. As Felix Salmon of Reuters points out, “By the time you’ve paid for your content and for your ad-sales infrastructure, the chances that you’ll have any money at all left over for your shareholders are slim indeed, and getting slimmer year by year.”

The future of news organizations is a lot of revenue sources — maybe as many as 30 or 40 — and none of them account for a substantial stake of the organization’s income. John Thornton, founder and chairman of the nonprofit Texas Tribune, uses the language “revenue promiscuity.” By combining the fundamental individual-oriented nature of the web with the advantages of a publishing platform, we can develop a range of new revenue streams. The grand retreat behind paywalls may work for a select few, but praying for a kind of collective Miracle at Dunkirk is not realistic — and such moves may result in miniaturizing outlets, making them isolated and increasingly irrelevant to broad public discourse.

On Election Day 2012, more than 20 percent of NYTimes.com traffic visited Nate Silver’s blog. At the same time, his book had just been released. The Times had little role in Silver’s book. But imagine it had a big one; imagine the way it would open revenue possibilities, taking advantage of the giant platform the Times provided Silver. Publishing books, hosting events, and public speaking are just the beginning. Among the 30 or so contributors to Quarterly Co. are at least three regular writers for The New York Times. What is Quarterly Co., you ask? It is a subscription service that lets you “receive awesome things in the mail” curated by your favorite writers. Enjoy the work of Maud Newton, a regular contributor the New York Times magazine? For $25 every three months, she’ll send you a box of things she likes.

Decades ago, many newspapers had not yet fully adopted the convention of the byline — the journalist’s name at the top of the piece. Broadcast media, of course, focused their brands around the “talent” — news anchors and correspondents. Broadcast outlets made sure their signature voices and faces were a comfortable presence in citizens’ lives. (Talk radio, including NPR, capitalizes on these same dynamics.)

Newspapers and magazines walked tepidly in this direction, allowing pictures for columnists and the like. Consumers often associate the news brands with these columnists; they are the people many have woken up to, had coffee with, and yelled at over breakfast, lunch, or dinner. There is power in this idea.

But the reporters and editors mostly still remain faceless, locked behind an iron curtain of another age that was built to produce the veneer of objectivity. How many citizens can name the bylines of people they read? Vanishingly few. These journalists are like commodity producers on some outsourced, remote factory floor.

The social media era has brought about the beginnings of a new press ethic. Though there have been screw-ups, embarrassments, and lots of consternation about evolving newsroom norms, for the most part it’s been a net positive for the public to see journalists as human beings in the social sphere. Jay Rosen’s famous “view from nowhere” critique is still largely valid, but incrementally the digital age has started to change things, as more journalists move out from behind the curtain and become public figures in their own right.

Consider what it would mean to accelerate this trend, and to bring it fully in line with the logic of a Web 2.0 world in which social networks are paramount. There has been much talk about the need for journalists to establish a “personal brand” that transcends their outlet. Some news personalities now play a strong role on Twitter and Facebook, but they often get little institutional support for this, and such participation and engagement remain merely part of a narrow web traffic strategy.

But what if news outlets decided to flip their model, so that the editorial staff was not subservient to the brand, but the “brand” became a platform for talent? What if news organizations confronted the reality that nearly all media will be “social media” a decade hence?

Andrew Sullivan’s decision to create his own, self-branded news organization caused ripples across media circles. Many have wondered if he’s an outlier, sui generis, and whether his model, even if successful, might not be replicable. What he may do, in any case, is give more journalists a permission slip to create a bolder role that is more in keeping with the web future.

Other outlets, like Boing Boing, are making money largely based on the brands of several smart, interesting personalities. Many of the “blogging networks” are built around aggregating traffic across different online personalities. One could name dozens of examples where a single blogger or news personality is driving substantial traffic. And at the local level, there are always excellent reporters who could easily become the face and driving force behind news organizations, if fully empowered to do so.

As Ken Doctor has written here at the Lab, we’re already likely to see a “new dance between top talent and media brands,” with new revenue and distribution possibilities of all kinds. “If brands are successful at assembling enough talent,” he notes, “they’ll succeed because they provide easy entry points for us consumers.”

The overriding goal must be audience loyalty, and with it, the willingness to pay for work. Talented people — their voices, personalities, tastes and ultimately news skills and judgment — are the filters that digital era consumers want, not archaic, anonymous news brand names. In March of 2008, Kevin Kelly famously put forth the theory of 1,000 true fans as a potential future for music. Find 1,000 dedicated enthusiasts willing to pay you $100 a year for your music, and then you don’t have to worry about selling albums. To some extent, Kickstarter is build around this idea. Josh Marshall effectively utilized this approach to build a real news organization, and it provides a model that has seen remarkably little experimentation and deserves more attention.

NPR may have a lot to teach other news orgs: Tune into any public radio station during pledge week and “trusted” reporters, hosts, and producers cross the traditional “church-state” editorial line and ask directly for money. Why are more journalists not doing the same — and creating more kinds of editorial products to sell — while cultivating a paying fan base?

With the decline of trust and loyalty in large institutions, it is increasingly hard to imagine people in the coming decades subscribing because of loyalty to an institutional Big Media entity. Yet it’s easy to imagine them wanting to fund several people whom they trust to bring them information they care about.

Sure, the research to date shows that the average news consumer is a creature of habit, circling back to the same two to four big websites to get their news. But this will not continue in perpetuity, given the rising importance of social media. “Elite” news consumers — the people who today already read The Economist, the Times, The Atlantic, and niche sites like this one — already organize their consumption this way, around key Twitter and RSS feeds, following lists of personalities they like or admire. The broader public will ultimately begin to shift in this direction.

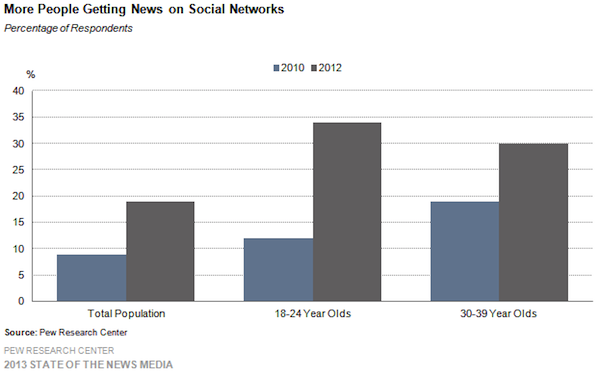

Pew’s 2013 report illustrates the fact that news consumers are increasingly getting their news through social sources.

What if news organizations acknowledged this — or even got out in front of it, ahead of the curve this time — and organized themselves as platforms for talent? Pew’s data suggest that 15 percent of people now report getting most of their news through social media. The news business should proactively plan for a day when that number will be 95 percent.

This means that were you to buy the Los Angeles Times, you might reorient it as 50 to 100 blogs that all have a common institutional home but are driven by news talents who convene discrete audiences. They could be armed by their news institution with video, audio, data visualization, research resources, and support.

At the organizational level, this would mean undercutting the corporate models and news managers and flattening organizations; there would be very little “brass” and manager class left, as organizations become ultra lean — stripped down to the raw talent.

To many, this would be scary: The traditional configuration of editorial layers and safeguards would change. As Bob Garfield notes at the Guardian, most new revenue stream ideas carry with them the potential for compromising “editorial integrity.” But the answer here is not to eschew new revenue ideas but rather to find new ways of ensuring standards. Smart, ethical journalists can handle this. And it is worth acknowledging that in a networked world, the prevailing ethic is to post news quickly, update, and iterate as new facts arrive; and the community audience often does much of the fact-checking, which is then folded into updates.

True, at an organizational level, this is not a wholly novel approach. Many outlets are getting their “talent” out there increasingly, having them do more media to help promote company brands. And there are already collaborative teams across news organizations involving reporters, videographers, researchers, and data visualization specialists. One example of an outlet already going in the direction of the talent platform might be Forbes. And “newer” outlets like TechCrunch or Gawker furnish interesting models.

That said, the bigger question is how to preserve those who will do the lion’s share of accountability and public interest reporting in America; and this means thinking about the legacy media itself in a more disaggregated way, as a hive of individual talents.

At about the time the Berlin Wall fell, there were roughly 56,000 editorial jobs among American newsrooms. That number is now likely below 40,000, according to Pew, and one can imagine it falling further. Let’s say it might stabilize at some point to about half its historical high, around 30,000.

The first thing that should be stipulated is: If that number ever fell to zero, it would be an unmitigated disaster for American democracy. Review the finalists for the Pulitzer, Peabody, or Goldsmith prizes in any given year, and you’ll see the litany of ills — corruption, waste, abuse, crimes of all manner — that would not have been exposed were it not for reporters patiently carrying out document requests, making phone calls, and doing accountability journalism.

The civic, and monetary, value of all this is immense. To take just one concrete example: How much is it worth to have a couple Los Angeles Times reporters save taxpayers millions by exposing municipal corruption in Bell, Calif.? Having more individual journalists convey this value directly to their audience will, in the digital age, be much more powerful than having corporate brands publicize their own importance.

Digital news organizations empowered by radical connectivity have made up some of the ground lost by the legacy media, but the achievements of most great accountability journalism are a function of both skill and time. And though a new generation of journo-coders, hard-hitting bloggers and transparency organizations have abundant skills and do admirable work, few people have hundreds of hours a month to pursue leads.

The question then becomes how those important few — the 30,000 or so serving this essential public purpose in the future — can be cultivated, empowered, rewarded and ultimately retained over many years to perform this vital role. Implicitly, then, the question about “saving the news business” is not about the businesses, but about the individuals who constitute them.

How can we best frame each journalist as a public good with huge intrinsic market and civic value? The answer begins with making his or her identity, voice and importance clear in a social context.

At a larger level, this is an issue of how to preserve institutions with core public-interest values in the Internet age. Journalism stands as the great test case, with much riding on its outcome.

John Wihbey is editor of Journalist’s Resource at the Harvard Kennedy School’s Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics & Public Policy. He is also a lecturer in journalism at Boston University.