You’d think selling subscriptions within iPhone applications would appeal to media companies: It’s a model that promises recurring revenue streams, and it matches up nicely with the way they’ve always done business in print. But surprisingly few have jumped at the opportunity; most news organizations seem to be sticking with traditional one-off apps — some paid, most not.

You’d think selling subscriptions within iPhone applications would appeal to media companies: It’s a model that promises recurring revenue streams, and it matches up nicely with the way they’ve always done business in print. But surprisingly few have jumped at the opportunity; most news organizations seem to be sticking with traditional one-off apps — some paid, most not.

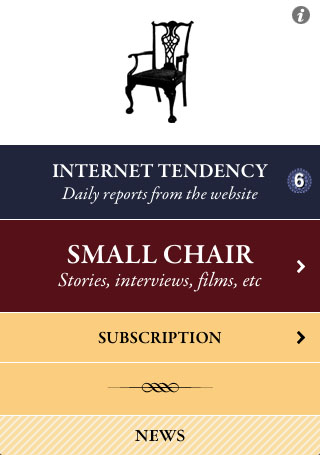

More surprising still is that McSweeney’s — the independent book/periodical publisher best known for its association with Dave Eggers and a predisposition toward narrow columns of text — is one of the first publishing-centric companies to capitalize on the possibilities that came with the most recent iPhone software update, including in-app purchasing and push notification. Apparently, the road to the future has aesthetic sensibilities — and maybe some lessons for news companies.

The McSweeney’s app sells for $5.99. Around $1 of that pays for the app itself; the remaining $4.99 buys a 180-day subscription to a special selection of McSweeney’s iPhone content, which they group under the label “Small Chair.” You can re-up for additional $4.99 180-day increments directly through the app itself — a nice feature for the clunky-fingered among us who hate filling out forms through the iPhone’s web browser. Apple takes a 30 percent cut from both the original purchase and subscription renewals, as it does for all iPhone purchases.

Russell Quinn, the software developer who built the McSweeney’s app, told me the decision to offer a subscription model was influenced by an interest in testing the iPhone’s new features and, more bluntly, a desire to make money. As TiVo can attest, the recurring revenue you get from subscriptions often eclipses one-off purchases. And from McSweeney’s perspective, a subscription model “seems to mesh really well with what we already do,” Eli Horowitz, McSweeney’s senior editor, told me over email.

Now, the line connecting McSweeney’s to a traditional news organization is neither short nor direct. McSweeney’s mix of fiction and whimsy provides a different context than hard news does. But there are a few aspects to the app that are instructive beyond the realm of hyperliterate periodicals.

— App usage: Getting attention in the App Store is a problem; with over 85,000 applications, it’s the Long Tail’s nemesis. But app vendors also face the growing disconnect between app installation and usage: It turns out that even those who buy apps rarely reuse them. But the McSweeney’s app has a solution for that: The weekly Small Chair updates are announced by a custom McSweeney’s chime, a small but notable callback to the app that separates it from its dockmates, at least until other developers follow suit with their own chirps, beeps, and R2-D2-esque clarion calls.

— Exclusive content: Small Chair material comes from McSweeney’s offline books and periodicals, which makes a Small Chair subscription digitally exclusive. This is material you can’t get on the web. To sweeten the deal, some Small Chair material will appear on the iPhone before it’s published in another McSweeney’s product. And iPhone-only content is on the drawing board as well.

The App Store is an anomaly because it’s a digital platform where users expect to pay — not always, but enough that it’s a common experience. Magazines, newspapers, broadcast outlets, book publishers, movie studios and other content firms could, theoretically, hold back certain types of material from free web spaces, and then push that same content out to paying iPhone subscribers as part of an exclusive digital channel. This won’t work for everything or everyone, but for companies that publish essays, chapters, long-form articles, short stories, films, and similar types of content, it could crack open a new subscription-based revenue stream.

— Value without subscriptions: App developers were originally allowed to sell in-app subscriptions within paid iPhone apps, not free ones, but that’s no longer the case. Free apps got an invite to the in-app party last week. This means The Wall Street Journal could release a free WSJ app and charge a subscription fee for access to premium content, whatever that might be. The McSweeney’s app was released before Apple’s policy shift, so Quinn is a taking a wait-and-see approach before instituting any changes.

Regardless, subscriptions bring up a unique customer service issue: How does an app maintain value after the subscription expires? Or, under Apple’s new rules, how can you provide free content that encourages users to upgrade? McSweeney’s answered the first question by making humor pieces from the McSweeney’s website always available through the app, even if customers let their Small Chair subscriptions lapse.

— Marketing other products: At its core, the McSweeney’s app is really an extensive sampler with a clever marketing hook. The app exposes customers to the publisher’s full offerings — which, if the dots connect and the stars align, could inspire app users to purchase other McSweeney’s products. And in an analog variation on exclusivity, Horowitz noted that those other products often include material that cannot be easily adapted for the iPhone.

So if a subscription model is so appealing, why haven’t more media companies jumped on the bandwagon? It could be a time issue — the iPhone’s new features launched in June, and software development doesn’t happen overnight. But Quinn brought up another hurdle: cost.

Under the traditional app scenario, most of the time and expense is frontloaded into the development process. A company hires a developer (or assigns one in-house); the developer builds the software; the app goes through the approval process; it launches; people buy it (or don’t) — and that’s where the road ends. Apple takes on the burdens of platform, distribution and fulfillment.

But with push notifications, updates are handled by the app’s developers, not Apple — which means companies need to invest in hardware and prepare for the scale issues that arise when registered devices and custom content need to be matched. “It takes out a lot of the bedroom coders,” Quinn said, referring to the mini shops that have sprung up as the App Store has caught on. Quinn estimated that half of his development time on the McSweeney’s app was spent on infrastructure setup alone.

While that extra investment may be costly for independent developers, it might give a short-term advantage to larger organizations (like media companies) that can more easily deal with things like scale and infrastructure. In an era when inexpensive tools have leveled the development playing field, that could be a rare push in the opposite direction.