Howard Rheingold isn’t too concerned about whether Google is making us stupid or if Facebook is making us lonely. Those kind of criticisms, Rheingold says, miscalculate the ability humans have to change their behavior, particularly when it comes to how we use social media and the Internet more broadly.

“If, like many others, you are concerned social media is making people and cultures shallow, I propose we teach more people how to swim and together explore the deeper end of the pool,” Rheingold said Thursday.

Rheingold was visiting the MIT Media Lab to talk about his new book, Net Smart: How to Thrive Online, which examines how people can use the Internet not just to better themselves, but also society as a whole. Rheingold has a longer online history than most, going back to The WELL, one of the first online forums back in the 1980s. Ever since writing about that experience, Rheingold has developed a habit for dropping the kind of book that not just probes what it means to be online, but charts what that means for all of us.

Net Smart is a book for an era where we’ve moved past just creating online identities and communities, but still have to educate ourselves on how to operate in day-to-day life. Rheingold said he believes a better understanding and deeper use of things like Google, Facebook, and Twitter are “essential survival skills” that will last beyond today or the lifespan of those individual companies.

The fact that those companies have grown so large so quickly has led to as much speculation about their financial futures as their impact on our attention span and privacy. But Rheingold says the analysis often focuses on the potential damages of these new platforms rather than their benefits. “Knowing that something is broken, or that there are costs to it we had not thought of when we first started using it, is not enough to tell you what to do or how to fix it,” he said.

Instead, Rheingold wants to focus on how we use these tools and how users can become more mindful and literate. Net Smart offers up a set of five literacies Rheingold sees as important: attention, participation, collaboration, “crap detection,” and network smarts. As we’ve become more sophisticated in the ways we use the web, we need to adjust how we use it, being able to tell fact from rumor and able to call on the skills and resources of a community to help answer our questions.

What distinguishes Rheingold’s work here is the attention to, well, attention. He’s talking about metacognition, or making ourselves more aware of what we’re doing online. We often divide our attention online, but at any given moment make “micro decisions” about what we’re going to do — write emails for work, watch a YouTube video, get lost in Twitter. Rheingold says we have to connect our attention to our intention and be more aware of how what we’re actively doing relates (or often doesn’t) to what we need. That helps when you’re looking for a restaurant recommendation, but also when you want to find accurate information about a court verdict.

“Finding the best stuff and sharing what we found is one way of improving ourselves, but also improving the commons,” he said.

In that way, attention connects with participation and collaboration. The act of sharing not only builds intelligence but shows good faith in a community. It also has a reinforcing quality; once you go from being a passive part of a community to liking, retweeting, and curating, you increase your activity as well as your value. The act of transforming information into knowledge and making it usable to people will always have value, no matter what platforms exist, Rheingold said.

“The proliferation of media has not stopped — if anything it has gone into hyperdrive,” he said. “If you want to keep up with anything, it’s not about keeping up with technologies, it’s about keeping up with literacies.”

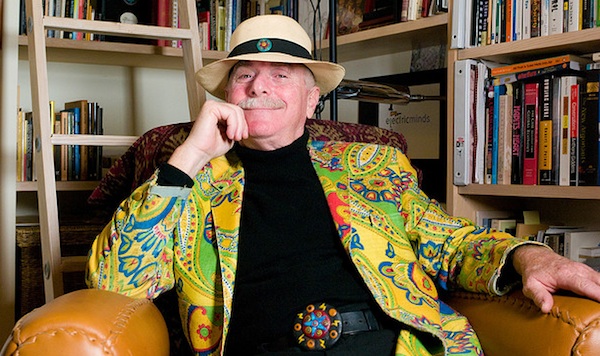

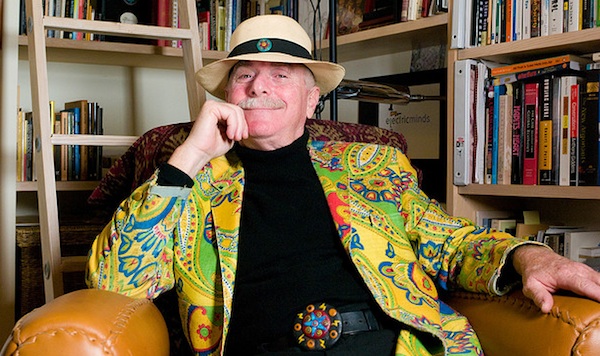

Photo of Rheingold by MIT Media Lab director Joi Ito used under a Creative Commons license.