“App-like” is a word you hear thrown around about websites more and more these days. News sites, in particular, want to look less like traditional pages-and-clicks operations and more like immersive, interactive experiences. From Gawker to Quartz to The New York Times web app to USA Today — HTML5, AJAX, responsive design, and a tablet-inspired aesthetic have conspired to try to make you forget about that Back button in your browser.

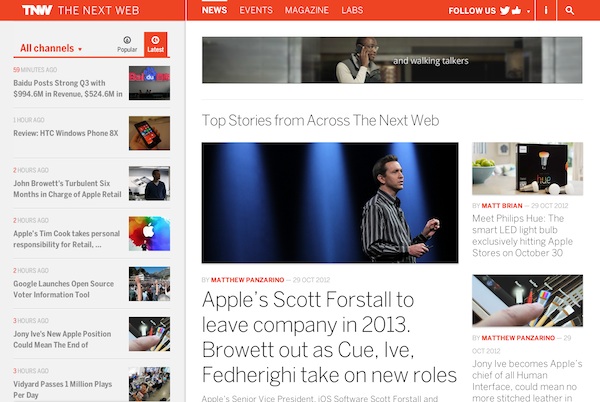

The latest to join the movement is tech site The Next Web, which debuted a redesign moments ago. (It’s still a bit buggy for me, but give them a break — it’s launch day.) Here are some of the highlights, which tie up a lot of recent app-y trends:

— Fuzzier boundaries between pages: “Thanks to HTML5, readers can now browse the site with fewer refreshes and near instant switching between articles.”

— The by-now de rigueur two-pane UI, with a reverse-chronological list of recent stories on one side and a story/promo well on the other.

— Keyboard shortcuts to move between articles with left and right arrows.

— Responsive design for mobile devices, with a nice portrait tablet look.

As this sort of approach spreads further among online-native news sites, how quickly will the underlying ideas penetrate the more traditional players, like newspapers?

Leave a comment