The text-based web is dead, says Michael Downing. When AOL CEO Tim Armstrong announced his intention this month to transform the company into a platform for video, Downing heard a death knell — one he’s been expecting for some time. We are, after all, as he says, on the precipice of “the rise of the visual web.”

Downing has a dog in this fight; he’s the founder of Tout, a video sharing website and app that makes it easy for users to upload and share short — under 15 seconds — videos in real-time. Although originally designed as a consumer device, it also appealed to publishers: The Wall Street Journal approached Downing with the idea for a proprietary app that reporters could use as a news gathering tool. With the addition of some analytics tools and a centralized management function that allows editors to quickly vet clips before they’re published, that became WorldStream, which we wrote about in August.

“Consumer behavior has become much more accustomed to consuming the news they want as it happens,” says Downing. “The WSJ was trying to be much more in line with real-time news and real-time publishing.”

More than half a year later, how’s WorldStream working out? The Journal seems pretty happy. On the business side, WorldStream point man and WSJ deputy editor of video Mark Scheffler describes the project as a “destination but also a clearinghouse.” While all of the WSJ’s mobile videos are first published to the feed, many go on to live second lives across a wide variety of platforms. Some clips follow reporters to live broadcast appearances, while others are embedded into article pages and blogs. Andy Regal, the Journal’s head of video production, said that they don’t break out WorldStream views from the newspaper’s overall video numbers, which he said total between 30 and 35 million streams per month.

That kind of traffic across platforms draws the attention of advertisers. The WSJ says video ads generate “premium” rates, meaning somewhere around $40 to $60 CPM. Says Tim Ware, WSJ director of mobile sales, of the Journal’s broader video strategy: “We’re very bullish on the growth of WSJ Live this fiscal year, and thus the growth in video ad revenue. We’re also starting to contemplate some one-off sponsorships within our overarching video coverage of select events and stories.” (After spending about a total of about an hour on WorldStream, however, I only saw one ad — for a “smart document solutions” company — repeated about a half dozen times.)

But the surprise, both for Downing and WSJ management, is how readily — and ably — the WSJ’s reporters have taken to the new medium; getting reporter buy-in has been a struggle for many newspaper video initiatives. “It started out as an internal tool because we didn’t know how many people would be able to accommodate this kind of approach with the technology and the software,” Regal says, “but they think about it as part of their daily work now.” Armed with iPhones, iPods, iPads, and Android devices, hundreds of WSJ staffers have filed video clips via Tout; in the 229 days since launch, that’s 2,815 videos. In many cases, Downing said, the reporters didn’t even need training: “They just jumped right in and started using it.”

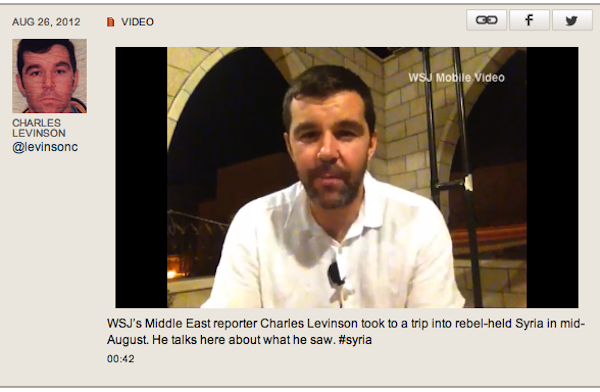

Charles Levinson has been reporting for the Journal from places like Syria “What are the assets that give us an advantage over the competitor? We have 2,000 reporters around the world,” he said. “How do you parlay 2,000 reporters into good video?” Levinson says the Tout app is helping the WSJ avoid print media’s tendency toward “mediocre” video production.

Christina Binkley is a style columnist at the WSJ who first experimented with the app while reporting on New York’s 2012 Fashion Week. She says there’s a lot of pressure on reporters to be producing a huge variety of content — articles, columns, blogs, Instagrams, tweets. She said, unlike some other apps, WorldStream has really stuck with her: “I can add a lot of value to my column very quickly without having to mic somebody up.”

Scheffler says some of the reporters have gained basic video shooting skills so quickly that the footage they file can be edited together into longer clips that could pass for more traditionally produced video. Going forward, Scheffler hopes to put better mobile editing tools in their hands: “Being able to be full-fledged creators on a mobile platform is something that we’re just going to continue being at the frontier of,” he said.

Regal’s focus, meanwhile, will be to make sure none of that prime footage is being lost in the ever quickening deluge that is the WorldStream feed. He’s considering a “Best of WorldStream” weekly digest, and a variety of other news packages that make that valuable content more findable, and more shareable.

News organizations have been chasing the promise of video advertising for years now, and the rise of apps like Vine illustrate the rise of social video sharing. But Downing says he isn’t worried about the competition. “Ninety-nine-point-nine percent of the existing video sharing apps have to do with self-expression,” he says, comparing Vine to something like Instagram. Tout’s enterprise apps skip the idea of sharing with friends and focuses on fast, concise updates from outlets that users follow based on broader personal interest.

“It’s a real-time, reverse chronological vertical feed of updates,” says Downing, “Whether it’s Twitter or LinkedIn, that is becoming the standard form factor for being able to track that information that you curate yourself.”

Since partnering with The Wall Street Journal last year, a number of publishers have pursued similar agreements with Tout — CBS, Fox, NBC Universal, WWE, La Gardere and Conde Nast are among them. By the end of 2013, Downing expects to host around 200 media outlets, including some of News Corp.’s other brands. Downing says these publisher agreements are now the company’s “primary mode of business,” not the consumer product.

What does Downing see coming in video? He confidently points to Google’s spring 2012 earnings report, when for the first time, its cost-per-click rate fell. “That was the sounding bell. That was the beacon. That was the one clear signal to the world that the era of the print metaphor defining the web experience…was over.”