Contrary to most popular accounts, the growth of the Internet has not obviously caused a large decline in newspaper readership. Readership has fallen steadily since the Internet was introduced in the mid-1990s, but it had been falling at almost the same rate since 1980, and the small acceleration of this trend accounts for a drop in readership of only about 10 percent. This is consistent with more systematic evidence in Gentzkow (2007) and Liebowitz and Zentner (2012), suggesting that online-offline substitution is relatively limited, as well as survey evidence showing that the Internet currently accounts for less than 10 percent of total time spent consuming news (Edmonds 2013).

In addition, he says print news lost more revenue when it lost its classifieds to sites like Craigslist than it ever did to online news.

For data, Gentzkow relied on comScore for online news traffic and the Video Consumer Mapping Study for print. Obviously, it’s much harder to measure minutes spent reading print than spent reading online, however, Gentzkow writes in an email:

…they actually had observers follow participants around and record what they do minute by minute. They find that the average person who reads a newspaper on a given day reads for 41 minutes.

Now these aren’t exactly comparable — one person could make multiple visits to a website on a given day, and subscribers probably read more than the average reader. But I think it’s clear as a ballpark estimate that the print number is an order of magnitude bigger than the online number.

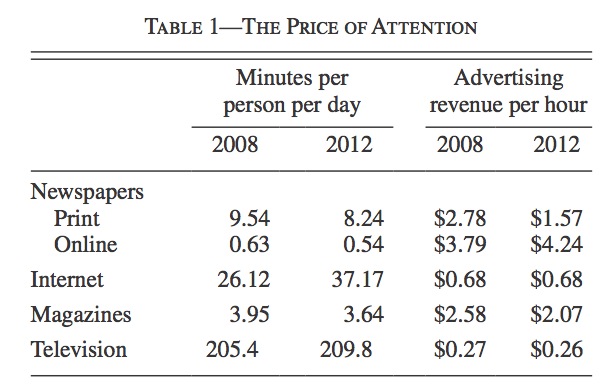

Based on these numbers, Gentzkow calculates that, although more money is spent on print advertising, when you look at spending per hour of attention, the rates for online are much higher.

Gentzkow offers a a few rationales for why online advertising might be valued more highly in the market.

Each newspaper has physical space for exactly one advertisement. All readers of the newspaper must see the same ad. The marginal cost of printing ads is zero. Each website also has physical space for exactly one advertisement, but these ads are targeted, so the website can show different ads to different consumers. Consumer types are observable to websites.

In other words, whatever online news lacks in eyeballs, it makes up for in delivering the intended viewer.

One comment:

Interesting but totally missed two letters: TV

Trackbacks:

Leave a comment