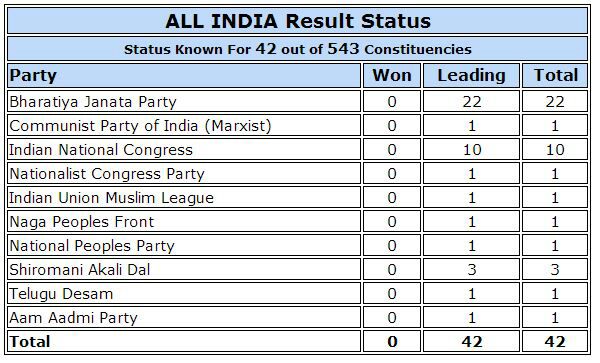

If you had followed BBC News India on WhatsApp on May 16, the day election results were announced after over a month of voting, you would have seen news updates in a variety of formats. In the early morning hours, there were alerts from vote counting, including screenshots of charts from the Election Commission:

When the losing side conceded defeat, there was a post with an update when Prime Minster-elect Narendra Modi tweeted:

India has won! भारत की विजय। अच्छे दिन आने वाले हैं।

— Narendra Modi (@narendramodi) May 16, 2014

A little later, the account posted this video of a celebratory parade:

Updates on final counts and local elections continued to flow in, half in English and half in Hindi. In the evening, the account posted a recording of Sonia Gandhi’s concession speech, followed by further results and transcribed statements, and then another audio recording, this one of BBC reporter Soutik Biswas giving his analysis. Toward the end of the day, the account posted a call out to the audience: “What’s your reaction to the election result? Send us your comments, including your name and location, and well try and feature some on our live page on the BBC News Website.” They followed up that post with this cartoon:

The coverage continued for another day or two, with assorted maps, charts, and other news headlines — all this on a messaging app that doesn’t even have a function that serves brands and, supposedly, has no intention of becoming a publishing platform. But around the world, traditional and new publishers are finding that chat apps have great potential for reaching new audiences and putting reporting into new contexts.

“If you were to ask people even a year ago, What’s the value of news organizations using WhatsApp?, people would have looked quizzically at you,” says Trushar Barot, an assistant editor in charge of user generated content, who leads BBC’s WhatsApp initiative. “People think it’s just a chat app — how do you scale that in any way for news activity?

“But the more I looked at it, I think it’s much more accurate to describe them as mobile-first social media sites, rather than just chat platforms.”

Barot’s interest in experimenting with chat apps for news began during the London riots of 2011. BBC reporters realized that protesters, especially teenagers, were using BlackBerry Messenger to communicate. “Here was a platform that was clearly being used a lot, but was a very closed ecosystem compared to the more open social media sites that we had access to,” Barot says.

Since then, Barot has taken the lead on experimenting with messaging apps at the BBC, where he’s interested both in their potential for distribution and for user generated content and source building. Barot selected the regions and platforms for his trial runs very specifically.

“We try to triangulate three things,” he says. “One, a market that we’re big in, or generate a lot of interest in. Secondly, where we think a particular app has got quite a lot of strength in terms of its user base. And thirdly, finding a big story that’s happening in that region.”

So far, that’s meant playing around with Mxit in South Africa during an election, WhatsApp and WeChat in India during their election, and BBM, the former BlackBerry Messenger, in Nigeria.

One of the biggest lessons of these experiments has been the way that platform infrastructure defines how users behave. WeChat, an app owned by Chinese tech firm Tencent, allows users to create personal profiles or subscription profiles1, which means they do a much better job supporting and distributing media. WhatsApp, on the other hand, has thus far remained set on being a very simple chat service. This means that users on WeChat are more likely to click links, while users on WhatsApp are more likely to comment and engage, and videos are more likely to go viral.

Barot’s two-week attempt at reaching a South African audience on Mxit — an app that appeals to the country’s younger, poorer market because it’s free and works on feature phones2 — was somewhat different. The BBC doesn’t have nearly as large an editorial outfit in South Africa as it does in India, which meant they were more strapped to come up with relevant content. “The plan was to try and see if we could engage a younger South African audience around content that BBC News was publishing and engaging them with comments and interactive elements within the app,” he says.

As it turned out, the app ended up driving BBC content as much as the other way around. Throughout the election, the dominant narrative in South Africa was that the top issues for voters were security and health. But a Mxit poll built by Barot’s team suggested otherwise — 65 percent of respondents said jobs were the key issue, while 25 percent said education was. That finding turned into additional BBC reporting.

Styli Charalambous, publisher and CEO of the Daily Maverick in Johannesburg, says their experiments using Mxit have met with success, and points out that in South Africa the second most popular brand on Mxit is a publisher, 24.com. Mxit “allows you to plug in an RSS feed and is essentially a new way to reach a different (younger) audience than we would normally be exposed to,” Charalambous writes. “Some of the bigger publishers are able to reach audience sizes that match or exceed their website traffic through Mxit.”

Reaching new audiences and expanding readership is definitely the goal behind the BBC’s experimentation with chat apps. “One of our objectives as a global news division is that by 2022 we want to double our global reach. Globally, at the moment, we have an audience of about 250 million people. The target is to double that to 500 million people by 2022,” says Barot.

Not only do chat apps have enormous user bases — nearly 400 million for WeChat, around 500 million for WhatsApp — but they also offer the promise of a direct connection with the audience. Compared to Facebook or Twitter where only a small fraction of followers will see content, Barot says, “on WhatsApp, effectively you have 100 percent hit rate for your audience, because it pings straight onto their phone and comes up as a popup, and they will usually read it within seconds or minutes of you posting it.” (The BBC wouldn’t release exact figures in terms of how many people are reading their content on these apps.)

Five or six years ago, Barot did the same thing for the BBC’s Twitter and Facebook strategy that he’s trying to do now for chat apps. “Now, we’re much better at identifying those new technologies as they emerge,” he says. But much of the American tech press was shocked back in February when Facebook acquired WhatsApp for $19 billion.

Dear all tech Pubs: get moving on that what the hell is WhatsApp story. Which is from replies the big messaging app for everywhere but US :)

— Danny Sullivan (@dannysullivan) February 19, 2014

In other parts of the world, independent journalists and news organizations are far ahead of the Western media when it comes to capitalizing on the huge user bases of chat apps. Let’s take a look at a few other examples of what they’ve accomplished so far.

In China, there’s almost nothing — from shopping to gambling to getting a job — you can’t do on WeChat. (See this fascinating slide deck from the consulting firm yiibu for more about how e-commerce and chat apps work differently in China — particularly starting around slide 71.)

“These days, you’d be naive to go without a WeChat account,” writes Paul Bischoff for TechInAsia. “It’s not uncommon for WeChat QR codes linked to personal accounts to appear on business cards.”

It makes sense that media brands would want to take advantage of the enormous potential audience, but in China, WeChat was an also exciting platform for independent journalists and bloggers looking to get around strict censorship laws. Researchers at the University of Toronto’s Citizen Lab have been studying how Chinese censorship plays out on social platforms. One of those researchers, Jason Ng, says there are two conventional views on the rise of WeChat over Weibo — one being that WeChat is simply a more dynamic product. But the other is that after last summer’s crackdown on journalists using Weibo, users were looking for a service that felt more private.

It’s hard to get a holistic sense of how journalism is being done on WeChat in China. The English-language China Daily goes by Real Time China on WeChat; like many Chinese-language publishers, they use WeChat to share short web articles with photos, from trending topics to headlines like “Tensions rise as Vietnam’s fishing vessel sinks.”

But there are other, less conventional uses for journalists on WeChat. By day, Wang Xing is an editor at Southern Metropolitan News who told me (via voice message on WeChat, translated by his wife) that he mostly uses the platform to talk to friends. But Wang Xing also runs a brand account on WeChat called Bad News, where he documents errors and misrepresentations in Chinese media, including state-run media.

“There is an absence of self-criticism in some newspapers,” Wang Xing told me. “There are so many repeated errors that I cannot stand by. So, I created this personal platform to critique and record this Bad News.”

For example, when CCTV (Central Chinese Television) ran a story that made it seem like Beijing had the most expensive Starbucks coffee, Wang Xing pointed out that coffee actually cost more in other cities — Moscow, Sydney, Paris, and Frankfurt, for example. CCTV also failed to factor real estate into their what the cost of producing Starbucks coffee is in Beijing, and to mention that an expert that appeared in the story worked for a company with a conflict of interest with Starbucks. “The problem is, I can’t report the error of CCTV in my newspaper. But I can analyze it in Bad News — that’s why Bad News exists,” he says.

Wang Xing doesn’t use WeChat to find sources, preferring Weibo, where he says he finds more reliable information. He also says most investigative reporters probably stay off WeChat, which is likely a good move — authorities cracked down on WeChat bloggers this spring, shutting down around a dozen accounts. One of those belonged to investigative reporter Luo Changping, who has become famous for using microblogging platforms to direct attention at government corruption. (Changping’s account now appears to be active, but he told me “it’s not a good time to talk.”)While journalists on chat apps in China are restricted by authorities, in Brazil, reporters are using them to wring transparency from their government. Juliana Duarte is a journalist with CBN radio in Brazil. The CBN website actively promotes the organization’s WhatsApp account, which they use to communicate with readers. (It’s not simple to follow a brand on WhatsApp — you have to get the phone number for the account, add it as a contact, and send a message before you receive updates.)

Duarte says the CBN audience loves to communicate by WhatsApp, especially when there’s a chance they might end up being interviewed on air. “They never stop, it’s incredible — we get messages at 1 a.m. or midnight,” she says. “Sometimes we have so many, we don’t see one message, and the person is mad!”

But all that messaging isn’t just mindless chatter. CBN listeners have repeatedly broken news for the station. In one instance, a listener sent a photo from their car of a fish that had fallen out of the sky — out of a bird’s mouth, it turned out — that was very popular online. Another time, a driver reported seeing a car plunge from Brazil’s famous Rio-Niteroi Bridge. “We thought it was impossible, but it was true — a driver saw the accident,” Duarte says.

But the most valuable use of WhatsApp by far, she says, is when listeners report shootings. “If there’s a gun shooting in the neighborhood, we receive about five messages from people saying the same thing, so we know it’s true. We call the police and say, We know about the shooting. And the police say, I don’t know. But we know, because we have messages saying that,” Duarte says. Duarte emphasized that CBN never publishes information they receive on CBN without verifying it, via interview, additional reporting, or photograph. Duarte says the newspaper Extra also uses WhatsApp, and the CBN station in Sao Paulo will soon begin using it in their newsroom as well.

There are really two major implications for publishers when it comes to chat apps. On the one hand, they’re great for pushing out content to potentially enormous, previously untapped audiences. On the other hand, they’re intimate, private platforms where readers feel more comfortable engaging one to one, which can result in news stories that would not have been uncovered otherwise.

One of the most common pieces of advice when talking social media and publishing is to meet your audience where they are. If people who might be interested in your content are hanging out somewhere, go to them — that’s the conventional wisdom. There are a few American brands — NowThis News, Mashable — who have experimented with news delivery and reader engagement on Snapchat, and BuzzFeed says they’re in talks to collaborate with a variety of chat apps, but apps like Mxit, WhatsApp, WeChat, Line, Kakao, and Kik all have growing user bases that aren’t being met by Western news sources. That situation creates an opportunity for publishers to take what they’ve learned about social strategy on platforms like Facebook and Twitter and apply them elsewhere.

The BBC will be pushing ahead with their chat apps strategy, Barot says. They plan to launch another trial campaign around the World Cup via WhatsApp and BBC Brasil.

“The challenge for us is going to be how we can effectively scale what we did with the Indian elections, which was very labor intensive at times, in a way that enables us to concentrate more on the editorial side rather than the mechanics of managing the content,” says Barot. “We have some ideas about how to do this, but we need to investigate them further.”