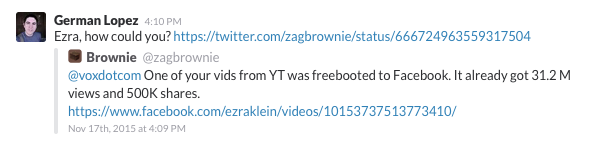

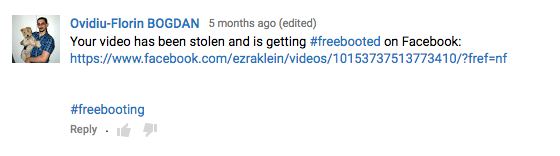

Last fall, Vox.com published a video on Syria’s civil war to its YouTube channel, where it’s ended up with nearly 2.5 million views. Vox editor-in-chief Ezra Klein also posted it to his Facebook page, where it racked up millions of views. (Today it has more than 53 million views and has been shared nearly a million times.) A few days later, Vox writers started getting tweets and Facebook posts accusing Klein of freebooting:

“The way this person knew Vox was as a YouTube brand,” Klein told me. “When he saw that someone was taking our videos and making them viral on Facebook and it wasn’t Vox, he was honestly upset.”

The anecdote goes to show that the Vox brand means different things to different people, and “explainer website launched by Washington Post wunderkind Ezra Klein” is probably not the most common.

“There are a lot of different Voxes,” Klein said. “Vox.com, the core site, is an important one, and a central one, but it isn’t the only one, and I’ve come to really believe that we need to value the YouTube following, the Facebook video following, the Snapchat following equally.”

That means thinking of videos as pieces that can stand on their own, not “the way to slightly better monetize an article page,” Klein said.

When Vox.com launched two years ago, none of its founders had much video experience. The video division began as a team of one: multimedia director Joe Posner, whom Klein had met at a conference. “What Vox video is, is almost entirely due to Joe,” Klein said. The team has now grown to 11 full-time employees in New York, San Francisco, and Washington.

Vox.com is wary of producing videos that feel too much like cable. “I made one rule starting out: no desks,” Posner said. A person sitting behind a desk talking, he thinks, is “one of those tropes of cable news that made their way into other news’ organizations’ first attempts at online video” and in many cases remains (you’ll see it all over Facebook Live videos, too).

Posner has also steered the team away from interviews (with a few notable exceptions, like President Obama): “There’s usually no reason to watch an interview. It’s better in text or as a podcast.”

“A lot of Internet video, especially from traditional media organizations, has evolved in a way that mimics the structure of TV,” said Matt Vree, Vox’s executive producer of video. Under that model, large teams take an assembly-line approach to creating a video, where each person has a specific role and the person who writes a script is not the same person who edits the video or publishes it to the Internet. By contrast, “the Vox team works like independent YouTubers.” For any given video, a single person is responsible for the entire production process, from pitch to publication.

“What’s made our team thrive is that we were scrappy at the beginning,” said Joss Fong, senior editorial producer and Posner’s first hire. Each person hired is “expected to have skills in all these areas. We’ve hired people at different levels, but when you set the expectation, people rise to the occasion. Every one of our team members has gotten up to speed on the process. You can’t not be invested, because it’s your idea, and you’re coming up with the design and look of it. It’s not an assignment that’s been passed down the line.”

One of Posner’s favorite videos was sparked by his hatred of a certain door in the Vox offices. The door looks as if it’s supposed to open out but actually opens in. Posner had become interested in the concept of human-centered design, which was pioneered by Don Norman a quarter of a century ago. Posner decided to “tell the story of the door” along with Roman Mars, the host of the podcast 99% Invisible.

“It’s a 25-year-old idea with no news hook,” Posner said. But by being creative and coming up with a narrative beyond an interview with Norman, he “could actually give people an introduction to an important concept in design.” The video has gotten nearly 2 million views on YouTube, and Mars devoted a podcast episode to it.

“It’s not you. Bad doors are everywhere” was just one example of how Vox’s video team has been inspired by podcasts. “Podcasts have a kind of history in radio in the same way that video has a history in TV,” Posner said. “The most awesome podcasts usually leave the radio confines behind, and end up creating something new that way.”

“I look for stories that are poorly suited for text articles,” said Fong. “We want to make sure we hit the stories that are specifically better in video.” Fong recently launched the second season of her science series, Observatory. A recent episode, “Proof of evolution that you can find on your body,” got more than 15 million YouTube views, accounting for about half of all Vox.com’s YouTube views in March.

“The unifying thread is that these videos are evidence-based deep dives, but not in a way that’s a buzzkill,” Fong said. “There is a lot of evidence-based work out there that’s more or less designed to debunk things people believe. I wanted to make Observatory more joyful, because that’s the way I feel about science.”

Eighty percent of Vox.com’s YouTube viewers are male. (In general, men spend much more time on YouTube than women do.) “I’ve spoken to other women who work in web video around news and science and they say the same thing. Where are the ladies, and why aren’t they interested in our content?” Fong said. “It’s tough because a lot of it is embedded in the way that video moves around the Internet. A lot of our views come from our fans submitting videos to Reddit, and Reddit is a heavily male audience. We’re still looking for the female Reddit. But I don’t know how to program specifically for women without pandering to them in some stereotypical way.”

Vox’s videos don’t seem gendered to me, and Fong agreed, noting that half of Vox’s video team is female. “Our videos are for everybody,” she said. “I’m more concerned that the people who are our audience are somehow not coming across our videos.”

Facebook may provide part of the answer: A roughly equal percentage of men and women share Vox.com’s videos on Facebook (and Facebook has slightly more female than male users). Vox.com has also started making a few videos specifically for Facebook, though Vree said the videos that perform best on YouTube are generally the same ones that perform best on Facebook. “The key differentiator for us is recognizing that people find your videos on YouTube through search, a day or two after you post,” he said. “Facebook is about being in the news, in the moment.” In February, Vox.com’s videos had their best month on Facebook ever, pulling in 99 million views. About half of those were driven by videos that Klein posted to his own page.

“It’s always been our intention with the video team to build audience and then monetize,” Klein said. “There are huge business and audience reach opportunities.” Vox.com plans to experiment more with Facebook Live, ideally in a way that “doesn’t just feel like we’re copying what we’ve seen on cable news. My expectation is that there’s going to be a lot of crap [from other news organizations] at the beginning.”

Vox.com is also pushing into new types of video programming. It recently launched its first host-driven, politics series, 2016ish, with Liz Plank. Coming later this year are a culture series, tentatively called “Vox Pop,” and an international, documentary-style series called Vox Docs.

Ultimately, if these new audiences never return to read Vox.com’s website, “it’s not necessarily something we can change,” Posner said. “We lead people around a bit, but it’s also just, well, that’s part of how the Internet works these days. We wouldn’t be reaching these people if we didn’t have different outlets, because a lot of them don’t read websites.”