Raney Aronson grew up without television. Her mother and stepfather were back-to-the-landers who moved the family to a rural Vermont town when Aronson was eight, grew their own organic food, and occasionally took Raney and her brothers and sisters to the local theater to see documentaries.

That gives Aronson, one year into her role as executive producer of PBS’s Frontline, something in common with the next generation of Frontline viewers: Watching stuff on TV isn’t a big part of their lives, either.

Frontline’s founder and original executive producer, David Fanning, never believed that Frontline was operating in some golden age of television, even in the pre-Internet era. “We have a minute to a minute and 30 seconds to prevent zapping,” he told The Washington Post in 1991. Frontline launched its first website, with supplemental materials for episodes airing on broadcast, in 1995, and began streaming some full-length episodes online in 2003. In 2002, on Frontline’s 20th anniversary, Fanning said in an interview with PBS:

How are we going to survive in the new age of digital television? With time-shifting and digital video recorders, when so much of the television landscape has become fragmented and noisy, when audiences have become accustomed to spending less and less time on a single story, it’s going to be a challenge for Frontline. Can we persuade our audience to look for us? In an era of disposable television, can we make television that lasts? And, can we sustain the hour-long narrative documentary? The answer, of course, is that we must.

When Fanning said that in 2002, there was no YouTube, Facebook, Netflix streaming, or iPhone. But his questions still apply in 2016; Frontline was just thinking about them early.

Aronson, 45, succeeded Fanning to become the executive producer of the 32-year-old Frontline just about a year ago. She originally joined Frontline as a senior producer in 2007 after making several films for the series, and Fanning primed her for the job over years in what she describes as “a high-end apprenticeship.”

To build her own team and ease her way into the role, “I was given the gift of time,” Aronson told me recently. Today, she leads a team of more than 35 full-time employees.

When I first met with Aronson, I admitted to her that I’d never watched Frontline until I started preparing for our meeting; I had only vaguely known what it was, and I went to its website and streamed a few episodes. This was embarrassing: To write about Frontline properly, I felt, I should have been watching it for years. To my relief, she wasn’t appalled. For Frontline to survive, it has to find new ways to connect with audiences who, like me, didn’t grow up with it; who will be stumbling on its clips on Facebook or YouTube, intrigued not by the formidable brand but by the subject and the content.

“I will always believe in documentaries,” Aronson said. “But I also believe in all of this other work. The biggest shift for us is saying that digital video is not promotional; it is, in and of itself, a powerful form that I want us to explore.”

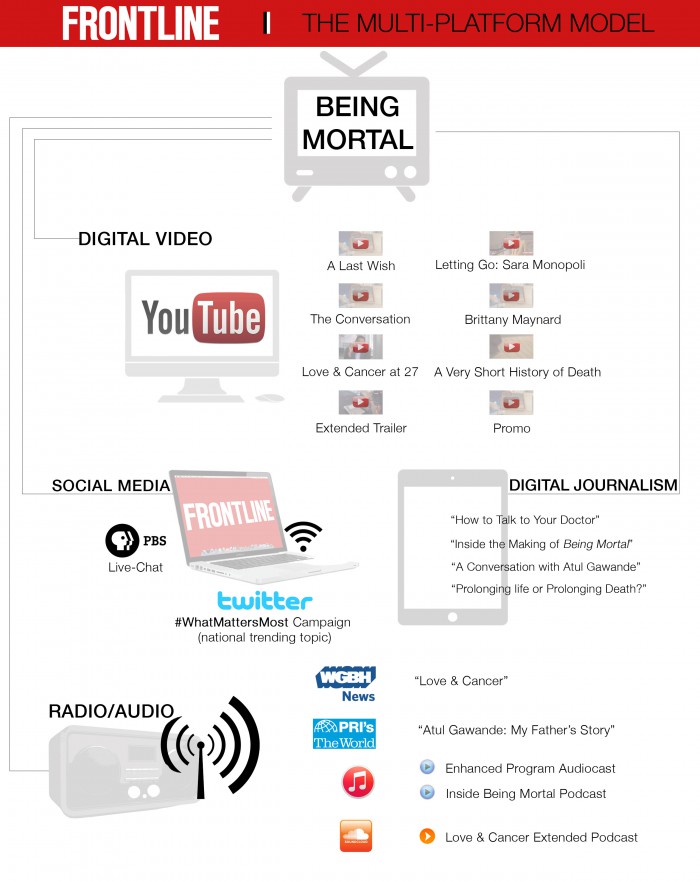

Digital video isn’t new to Frontline. In the early 2000s, it began streaming its full-length documentaries online. But broadcasting a film is no longer the end of the job, nor does it even have to be the beginning.

“We’re still a big PBS broadcast, we absolutely are, and we’re also a big streaming film series online,” said Aronson. “The moment it airs, it’s digital.” The creative work being done on digital video is run out of Frontline’s senior editorial team, which includes Aronson; Carla Borras, the 33-year-old series coordinating producer who has become Aronson’s right-hand woman; managing editor Andrew Metz; and senior producer and commissioning editor Dan Edge. “The audience team is right there with us as we’re creating these moments,” Aronson said. “That collaboration has taken us to new levels.”

Facebook-first films, for instance, have become a major part of how Frontline launches its full-length documentaries into the world. “These are short films that have their own integrity to them. They are really righteous filmmaking in their own sense,” Aronson said. The team has created a new term for these films: “social journalism.”

Aronson and Pam Johnston, Frontline’s senior director of audience development, stressed that the Facebook films have helped them to grow their audience across all platforms, without one group cannibalizing another. The turning point came last fall with a Facebook film called “School of ISIS,” released in response to the Paris terrorist attacks.

Frontline’s editorial, film, audience, and social video teams met to discuss what they could add to the coverage of the attacks. There happened to be a Frontline team covering the rise of ISIS in Afghanistan; the full-length film was set to air the following week. Senior producer Edge worked quickly with the Afghanistan team to pull together an original Facebook film that was released the Monday following the attacks.

“School of ISIS” reached 93 million people and was viewed more than 22 million times. “We’d never seen anything like this before,” Aronson said. “Our ecosystem is now so rich and collaborative that we can take a moment like Paris, think collectively, and then watch as it goes viral.”

“Five years ago, no one at Frontline focused on, talked about, or necessarily cared about an audience,” Johnston said. “It was mission-driven, and the content was created because these stories needed to be told. How and when these stories reached their audience was for other people to worry about — certainly not the makers and the journalists here at Frontline.”

Aronson began making films for Frontline when she was 31. In her mid-twenties, she had worked on ABC’s Turning Point, and it was then, she said, that she knew she wanted her career to be in longform film. She made seven films for David Fanning; the last one, “News War,” looked at change in the newspaper industry. “I was sitting inside The Washington Post and The New York Times learning about disruption,” Aronson said. “It hadn’t quite happened yet to the television industry. But having to think about it was such a great education.”

There are now a massive number of entry points to a Frontline film. There is, of course, broadcast, where a new Frontline film pulls in, on average, 2.5 million viewers, more than two-thirds of whom are over the age of 50. (28 percent are 18 to 49, and 13 percent are under 18.) The web audience, meanwhile, is almost the inverse of the broadcast audience: 70 percent of Frontline’s web visitors are between the ages of 18 and 49.

There are now a massive number of entry points to a Frontline film. There is, of course, broadcast, where a new Frontline film pulls in, on average, 2.5 million viewers, more than two-thirds of whom are over the age of 50. (28 percent are 18 to 49, and 13 percent are under 18.) The web audience, meanwhile, is almost the inverse of the broadcast audience: 70 percent of Frontline’s web visitors are between the ages of 18 and 49.

“If you watch us online, it still counts,” Aronson said. “If you timeshift us and watch us on your DVR or Apple TV, it still counts as someone watching our film. This has been a big shift, to be able to count those people. The actual people watching our full-length films is going up.”

There are also people who come to Frontline before they have ever seen one of its full films, through Facebook or YouTube. Frontline is “ever-cognizant” of concerns that publishers are giving platforms too much power, Aronson and Johnston said. The films that Frontline publishes on PBS.org and on PBS stations across America continue to drive the brand’s biggest audience. “But when we publish on social media, it helps our entire ecosystem grow,” Aronson said. “We’re finding new people on Facebook and bringing them under the tent of Frontline.”

“We’re careful, and we know that Facebook wants to keep everyone on Facebook,” Johnston said. “But when we put more on Facebook, our audience rose exponentially. We’re seeing people coming from Facebook to our website; the referring traffic is huge, and it’s only getting bigger.”

“You can’t make someone share [a video],” Borras said. “It has to resonate, to be so powerful that people are actually willing to go the extra mile of wanting their friends and family to see this.”

She mentioned another Frontline Facebook-first film, “Slaves of ISIS.” “If you go to the comments of it, so many people were like ‘Wow, Frontline!’ They didn’t act as if they knew it. They were like, ‘Oh, I want to check this film out.’ We had really clear language that there was a fuller film that you get to watch and it’s coming soon, and there were multiple comments about that: ‘This thing Frontline, crazy! I can’t wait to see the documentary.”

Borras has been at Frontline for seven years, starting out as an editorial assistant. Her first job out of Harvard was in New York, working on a feature film project. “I found myself dying inside,” she said. “I was like really, are you serious, is this what I’m doing with my life?” Home for a weekend in Waltham, Borras went to see a screening of “Storm Over Everest.”

“David Breashears, the incredible mountaineer camera man, was there,” she said. “And” — her voice dropped — “Raney was there. And I basically made it my mission to get inside Frontline. So that’s what I did.”

Borras wasn’t alone, among the employees I interviewed, in describing her work there as a calling and Aronson as a magnetic force. In a meeting with Borras, managing editor of digital Sarah Moughty, Pam Johnston, and senior producer Shayla Harris, I heard repeatedly about Frontline’s journalistic values, the amazingness of its producers, its reporting, its quality and integrity and brand, and about Raney Aronson.

I’ve sat in a lot of meeting rooms and heard company pitches; this was different. The women directed questions to each other — “That one’s for Pammy” — and seemed to operate in sync, in the easy way of people who’ve worked together for a long time and respect each other deeply. I felt a bit as if I were being convinced, though not in a creepy way, to join the church of Frontline.

I felt the same way later, when I sat in the back of a cab with Aronson on her way to a lunch with Google to discuss their virtual reality collaboration. (Frontline launched its first-ever VR documentary, the award-winning “Ebola Outbreak,” last fall on Google Cardboard, Facebook 360, and other platforms. It’s since launched two more 360-degree films on Facebook, “On the Brink of Famine” and “Return to Chernobyl,” and is committed to releasing at least ten more.) She talked about the effort she’d put into building her team, raving about Borras as enthusiastically as Carla had spoken about her. Aronson said she is always worried that Frontline will lose Carla to New York again. “But maybe we can just keep promoting her and she’ll stay here forever.”“I’m a millennial myself, and I feel very strongly that they just don’t know who Frontline is,” Borras said. “But if they did, they would actually really love this stuff.” She mimicked the way her friends talked about last spring’s HBO miniseries “The Jinx.” “They’re like ‘Oh my gosh, it’s incredible, look at this investigation unfold!’ They’re like, ‘Oh! Vice! Look at this reporter going out, he’s in, what, war-torn Syria? Wow, that’s badass!’ We’ve been doing it for 30 years, okay? And it’s just about making sure that that young audience knows about us in the same way the 60-plus-year-old audience knows about us. They’re not growing up with Channel 2, so how do we reach them?”

“We often talk about coming at the world with fresh eyes and openness,” Aronson said. “Not just coming in with this whole construct of what the world is, but being more open to what the world could be. This is philosophical. But it is part of who I am. I am always asking the younger people on our staff, What do you want to do with your life? This is about our lives. And running Frontline, it’s my life, too…That means that when we move onto other platforms, we’re doing it in a really meaningful way. We’re not just doing it to grow an audience. We’re doing it because I want to reach people on those platforms. It’s really important. Those people are there. We need to go there.”

“If our numbers aren’t going up and to the right, we’re dead,” Johnston said. That has meant that Frontline has changed some of the ways it does things. Until recently, for instance, the mentality had been, in Borras’s words, to “keep all the goods until the very end, and then we’re going to blow everybody’s mind and release all the big gets.”

But now stories are being divvied out sooner, before the full-length film airs. For instance, in the case of the Ebola project that Frontline worked on with The New York Times, Dan Edge was tasked from the start with coming up with ideas that could be used as an individual, standalone story to promote the full-length film.

“At first, he was like, ‘Oh, are you serious? Additional work?'” Borras recalled. “But he said it ended up being incredibly useful for informing scenes in the film going forward.” Frontline released “Ebola’s Patient Zero,” which is 5 minutes and 33 seconds long, online on December 29, 2014 (in conjunction with a major Times story on the outbreak). The full-length film, “Outbreak,” wasn’t released until May 25, 2015.

In other instances, films that were meant to be digital-only have inspired longer broadcast treatments. Frontline released “Stickup Kid,” a YouTube original film about a 16-year-old caught up in the adult criminal justice system, as a digital exclusive in December 2014. It’s nearly half an hour long. “Most people say that 28 minutes on the web is a killer, that you just want snackable stuff online,” Harris said. “And this is one of our most popular pieces on YouTube.” “Stickup Kid” was successful enough that it will probably be updated.

The challenge, said Moughty, is to make sure that audiences know the material is from Frontline “no matter where it is” on the web. The goal is “to make sure that we’re expanding Frontline’s DNA, not diluting it.”

Aronson is confident that this is going to work.

“The more I put myself into my job, and I wasn’t trying to do something else, even for David,” she said, “the more successful I became. That’s what David encouraged, the whole way through. Even when I was a filmmaker, he said: Find your own voice, and don’t become somebody you’re not because you think that’s what Frontline is.”

“We are Frontline,” she said. “It’s not the idea of Frontline. The people who make Frontline are Frontline.”