Few would argue that, in theory, the sharp increase in mobile access hasn’t been a good thing for individuals and society as a whole. A more connected public is a more informed one, and increased mobile penetration means more people are able to connect more often than ever before.

But according to a new report from Harvard’s Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy, there’s a dark side to the mobile revolution, which threatens to create a less engaged “second-class” citizenship of news consumers who don’t benefit from mobile adoption as much as everyone assumes. A more mobile public could, paradoxically, become a less informed one.

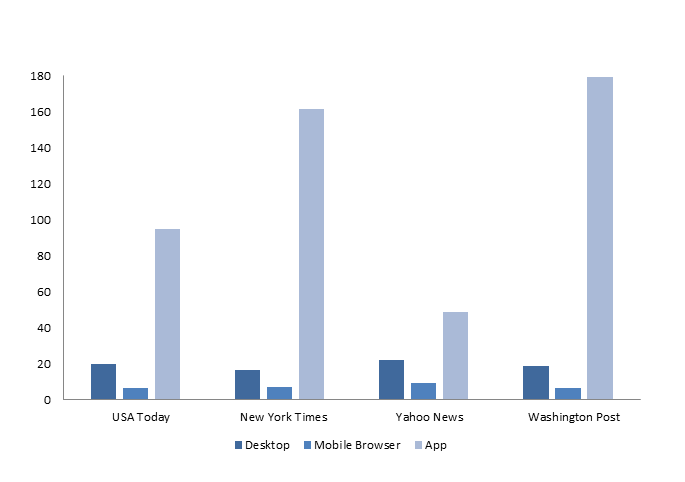

Johanna Dunaway, the report’s researcher and a recent fellow at Shorenstein, blames smartphones themselves. Thanks to a combination of smaller screens, slower connection speeds, and the variable costs of data, mobile devices are, in many senses, imperfect vectors for news consumption. Using eye-tracking software, Dunaway and her fellow researchers were able to monitor how people engaged with news on their phones. Their conclusion: “We found that, relative to computer users, mobile users spent less time reading news content and were less likely to notice and follow links and to do so for longer periods of time,” Dunaway said. Their findings are supported by previous data from Pew Research, which found that, while most sites now get more visitors through mobile than desktop, readers tend to spend far less time reading while on mobile devices.

Considering that two-thirds of all online activity is expected to happen on mobile devices by 2020, the implications of a mobile-dominant public are grim, the report argues. Dunaway ties the mobile risks to the many other challenges facing news organizations, which struggle to inform people in a media ecosystem dominated by choice, fragmentation, and news consumers gravitation towards sources that confirm their beliefs and enforce their biases.

Ultimately, all this means that while mobile is helping news organizations reach more people than ever, the problem is that those mobile news consumers are less engaged, less informed, and more likely to pay attention to sports and entertainment news than politics coverage. More, the rise in mobile adoption is most pronounced among Latino, black, and low-income Americans, which creates its own set of challenges, as Dunaway points out.

It may be correct to conclude, as some already have, that we are entering an era of second-class digital citizenship led by a mobile-only digital underclass.

A conceivable result is a widening disconnect between those who are politically interested and informed and those who are not. Given that this disconnect falls along income, racial, ethnic, and occupational lines, the effect could be an acceleration of the divide between America’s haves and have-nots — this at a time when that divide is already a source of political concern and unrest.

Leave a comment