German daily Die Welt has taken the strategy of countering falsehoods and hate speech with more speech to heart on its Facebook page.

It began in the fall of 2014 with lighthearted, sometimes snarky, sometimes earnest responses to comments on its Facebook posts, ramping up the frequency of official responses from the verified Welt account with a new two-person social media staff. The team took to trolling trolls with memes and gifs, amusing others with pop culture references and jokes, thanking those who wrote insightful comments, on top of addressing questions about the outlet’s editorial decisions and helping with social verification during breaking news coverage. Die Welt reads emails from readers, but perhaps even more admirably, it reads all its Facebook comments (tens of thousands per day) and makes sure its official account’s voice is present in the comments below every post on its page.Hier ein paar Beispiele für die Kommentare der @welt #rp17

Eingreifen, klare Ansagen, Humor, Smalltalk, Gegenrede, Mehrwert, Service. pic.twitter.com/YKjFI0TSvs— Niddal Salah-Eldin (@Nisalahe) May 8, 2017

“People come looking for a community, for companionship. Sometimes they actually just want to make small talk with us,” Niddal Salah-Eldin, head of social media for WeltN24, said. “We have to protect these people from all of the online hatred that is going on, but part of the reason why we do this is not only to get rid of the trolls and haters — we want to make sure people feel encouraged to leave comments on our page.” (In the last two years, Die Welt integrated with 24-hour news channel N24, which its parent company Axel Springer acquired in 2013. The group is now formally known as WeltN24, but the Facebook initiatives described in this piece are currently limited to just the Welt page.)

The Welt page’s cheeky tone so disarmed visitors that Facebook users unaffiliated with the paper set up a separate fan page for the “Die Welt intern,” which itself garnered almost 60,000 followers. Three years later, with the German federal elections looming, the official Welt account has taken on more explanatory and fact-checking work as well. A common reader question lately: If he’s misstepped as much as news coverage says he has, why hasn’t Donald Trump been pushed out yet? When readers ask very specific questions (e.g. “What type of airplane is this?”) the social team can’t answer, it takes pains to check with editors and reporters; Welt is trying to encourage more of its journalists to jump into the conversation on social media themselves.

“We’ve put more emphasis on what I’ve been calling counterspeech. If someone comments on our post with numbers, and the numbers they’re quoting are not from a credible source, we will respond. But we’re not just doing it for the person challenging us — you could argue that person is a troll who puts out fake numbers to get us to respond to them,” Salah-Eldin said. “We’re doing it for all the people on our page silently reading, who think, these numbers about refugees seem very high, but maybe it’s true? Then the comment stands there uncountered.” (ProPublica has taken a similar route on Twitter; its audience engagement team regularly tweetstorms facts and context around newsy issues, with the “no-bullshit-and-speaking-bluntly vernacular of social.”)

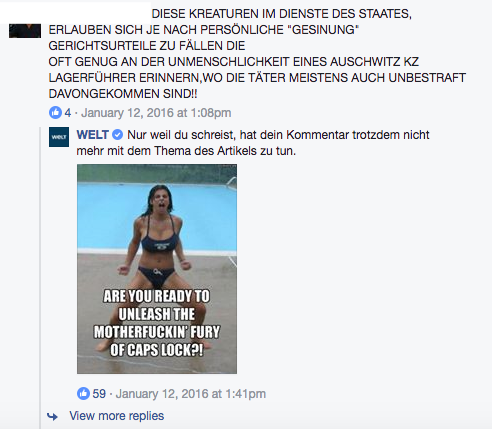

Die Welt’s Facebook page now has 930,000 followers, up from around 220,000 three years ago when its efforts to develop a distinct personality for the outlet first began. (“My team doesn’t buy traffic; we don’t pay to boost posts,” Salah-Eldin told me.) Die Welt left Facebook’s Instant Articles initiative in March after cutting load times for its own pages, though it’s still making live videos. A significant number of other posts on its page are ubiquitous viral native video that spark easy banter between Die Welt and commenters, but even with more politically charged topics, the official account still valiantly dives into the comments to demand civility. Some of its comments are intended as mini mic drops that draw a swarm of likes on Facebook:

The social team has expanded to five full-time editors, who work in shifts monitoring Die Welt’s channels from early morning to late at night, including weekends. (Salah-Eldin was recently promoted to director of digital innovation for Die Welt, a position she’ll start next January.) Before Salah-Eldin and her team formally took over revamping the outlet’s social media strategy, Die Welt online editors had to handle posting stories to social on top of writing and editing; now the team has a suite of social monitoring and community management tools at its disposal from Chartbeat to Social Hub and is testing another tool developed by an external group at a hackathon to help manage comments.

“Our bosses knew what we were going to do, and trusted us. If we had a process where someone had to sign off on everything,” Salah-Eldin said. “This is all done in real time, and when it takes a while until our response is out there, it loses its charm.”

The German media has been bracing for hacks and leaks. Its government is prepared to fine social platforms like Facebook that don’t delete “illegal content” within 24 hours as much as €50 million. Other news organizations are launching dedicated “anti-Fake News” fact-checking units. Facebook has been trying to build up its outsourced fact-checking operations in the country, with limited success. Salah-Eldin said her team is interested in a different framing.

“Many of the questions we get are not, ‘Hey, this is fake news, delete your page.’ Bottom line is, we’re not engaging in a debate only about is this fake, yes or no,” she said. “There’s deep interest in how we cover stories, why we picked one story and didn’t pick up on another story. Why didn’t you cover whatever was going on in my town, why can’t I read about it in Welt? There’s a curiosity and a request for more transparency.”

As news outlets turn their attention to paying subscribers, they’ve increased efforts that help strengthen affinity with readers, whether through interest-based Facebook groups (all the rage, see here, here, here, or here) or carving out a dedicated team to work on reader-focused projects. Welt maintains a private Insider page for people paying for the most expensive tier of products, where product managers and developers visited to give updates and ask for feedback during an app relaunch process. It has a close relationship with another invite-only Facebook group of Welt superfans, who created a group independently, but may sometimes serve as beta testers for the news organization when it’s looking to launch new formats such as Facebook Live. Welt even brought a few dozen of these members to its Berlin offices for a closed discussion with newsroom leadership (plus a meal together).

Welt switched from a metered paywall to a freemium one last September; its social media initiatives, too, need to nudge readers ultimately towards buying premium subscriptions.

“There are readers who might remember the positive experience they had on our page, who remember we liked their comment, or showed them we appreciated when they wrote interesting comments. When they want to take out a subscription, they remember, Welt was the page that interacted with them,” Salah-Eldin said. “The ability to recognize a brand — this is a huge thing right now. We don’t want people to say, ‘I read this on Facebook.'”