The growing stream of reporting on and data about fake news, misinformation, partisan content, and news literacy is hard to keep up with. This weekly roundup offers the highlights of what you might have missed.

Many smart people are still very bad at evaluating sources. Stanford’s Sam Wineburg and Sarah McGrew observed “10 Ph.D. historians, 10 professional fact checkers, and 25 Stanford University undergraduates…as they evaluated live websites and searched for information

on social and political issues.” What they found:

Historians and students often fell victim to easily manipulated features of websites, such as official-looking logos and domain names. They read vertically, staying within a website to evaluate its reliability. In contrast, fact checkers read laterally, leaving a site after a quick scan and opening up new browser tabs in order to judge the credibility of the original site. Compared to the other groups, fact checkers arrived at more warranted conclusions in a fraction of the time.

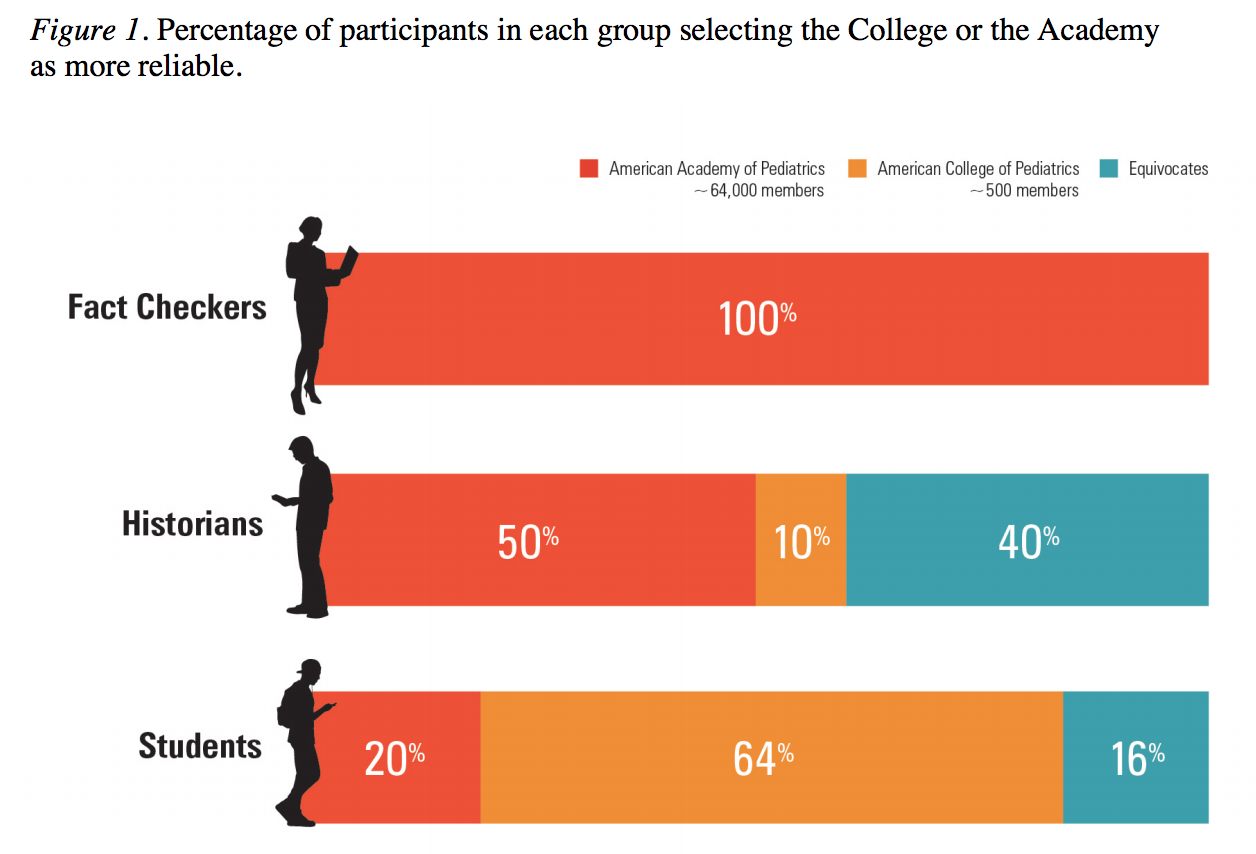

In one exercise, for instance, participants were asked to compare articles from two sites: One from the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the other from the American College of Pediatricians. The two organizations sound similar, but are very different:

The Academy, established in 1932, is the largest professional organization of pediatricians in the world, with 64,000 members and a paid staff of 450. The Academy publishes Pediatrics, the field’s flagship journal, and offers continuing education on everything from Sudden Infant Death Syndrome to

the importance of wearing bicycle helmets during adolescence.By comparison, the College is a splinter group that in 2002 broke from its parent organization over the issue of adoption by same-sex couples. It is estimated to have between 200-500 members, one full-time employee, and publishes no journal (Throckmorton, 2011). The group has come under withering criticism for its virulently anti-gay stance, its advocacy of “reparative therapy” (currently outlawed for minors in nine U.S. states), and incendiary posts (one advocates adding P for pedophile to the acronym LGBT, since pedophilia is “intrinsically woven into their agenda”) (American College of Pediatricians, 2015).

The American College of Pediatricians doesn’t hide its positions, but “students overwhelmingly judged the College’s site the more reliable” — as did a fair percentage of historians.

“They seemed equally reliable to me. I enjoyed the interface of the [College website] better. But they seemed equally reliable. They’re both from academies or institutions that deal with this stuff every day,” one student said.

Another said, “Nice how there’s not really any advertisements on this site. Makes it seem much more legitimate.”

The whole paper is really fascinating, very readable — the best thing I’ve read so far on digital literacy. Don’t miss the section at the end that talks about where schools’ media literacy curriculums — with their easily gameable checklists — may be going wrong.

Most of the other digital literacy content I’ve read focuses on funny things middle schoolers say, or focuses on the immensity of the problem. But the skills outlined in this paper — the authors call them “heuristics” — are very teachable, they’re not hard to explain, and they can be easily incorporated into curriculums. Read it.

Could Facebook help more people act like factcheckers? Shane Greenup argues that a recently announced Facebook feature that adds context to shared links could actually be successful because it helps more people do the type of lateral reading that the Stanford study outlines. Facebook is “on to something genuinely valuable that is actually pretty hard to game, and sufficiently open to user choice without telling people what they should be accepting as true and false,” Greenup writes.

And now it is time to stop saying nice things about Facebook:

Facebook hides the data that had let one researcher look at the spread of disinformation. Strangely timed “bug” or the obfuscation of information? Last week’s column led with the story that the Tow Center’s Jonathan Albright had found a way to determine the extent to which disinformation was shared by six Russian-controlled, election-related, now-defunct accounts — and the spread, Albright determined, was huge: In the hundreds of millions.

Albright had used the Facebook-owned CrowdTangle to analyze the posts. But now, The Washington Post’s Craig Timberg reports, Facebook has “scrubbed from the Internet nearly everything — thousands of Facebook posts and the related data — that had made [Albright’s] work possible. Never again would he or any other researcher be able to run the kind of analysis he had done just days earlier.” (Also in The Washington Post, George Washington University associate professor Dave Karpf argued for caution in accepting Albright’s analysis since CrowdTangle data can be very hard to analyze accurately; still, he noted to Timberg, “Any time you lose data, I don’t like it, especially when you lose data and you’re right in the middle of public scrutiny.”)

Facebook told the Post that it had merely “identified and fixed a bug in CrowdTangle that allowed users to see cached information from inactive Facebook pages.” What interesting timing. On Thursday, Facebook COO Sheryl Sandberg told Axios’s Mike Allen that “things happened on our platform that shouldn’t have happened” during the 2016 presidential campaign, that “we’ll do everything we can to defeat [Russia],” and that Facebook owes America “not just an apology, but determination” for its role in allowing Russian interference to take place.

Takeaways of Sandberg interview @mikeallen @axios today:

First off, basically no question was answered. Lots of scripted talking points /1

— Molly McKew (@MollyMcKew) October 12, 2017

It’s backed up. https://t.co/B5SUgWEsg9

— J0nathan A1bright (@d1gi) October 12, 2017

Meanwhile, lawmakers plan to release the 3,000 Russian ads to the public “after a Nov. 1 hearing on the role of social media platforms in Russia’s interference in the election,” writes Cecilia Kang in The New York Times. “That hearing, and a similar one that the Senate Intelligence Committee plans to hold with Facebook, Google and Twitter, will place Silicon Valley’s top companies under a harsh spotlight as the public perception of the giants shifts in Washington.” (Pokémon is under scrutiny as well.)

tfw google alerts finds an article about fake news from a fake news fraud site that has fabricated a quote that you never said. wtf. pic.twitter.com/hx4gMT05nT

— David Carroll (@profcarroll) October 12, 2017

Facebook says its fact-checking stuff is working. From a leaked email to Facebook’s factchecking partners, published by BuzzFeed:

We have been closely analyzing data over several weeks and have learned that once we receive a false rating from one of our fact checking partners, we are able to reduce future impressions on Facebook by 80 percent. While we are encouraged by the efficacy we’re seeing, we believe there is much more work to do. As a first priority, we are working to surface these hoaxes sooner. It commonly takes over 3 days, and we know most of the impressions typically happen in that initial time period. We also need to surface more of them, as we know we miss many.