After six months of investigating thousands of disciplinary cases in dozens of police departments around Cincinnati, Scripps TV station WCPO was almost ready to share its findings on air and online. But the team decided to add one more thing to their to-do list: an on-air segment and online letter about why and how they did it.

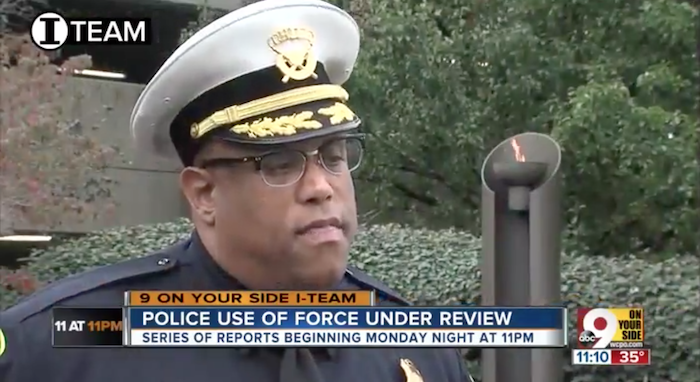

“Our motives are simple: We want to make sure the people who protect us and enforce our laws are worthy of the high level of trust the public gives them,” wrote Mike Canan, then WCPO.com’s editor.“Our goal is to show you if police departments are transparent about how they respond to findings of misconduct, if the punishment fits the behavior, and what can be done to provide a better system of checks and balances that benefit police — and our community,” explained Craig Cheatham, the station’s chief investigative reporter, in an on-air preview of the investigation during the evening news.

This new approach was spurred by WCPO’s participation in Trusting News, an initiative created by engagement strategist Joy Mayer and supported by the Reynolds Journalism Institute, Democracy Fund, and the Knight Foundation. (Disclosure: Nieman Lab also receives support from Knight.) In an interview, Canan said if WCPO hadn’t been working with the project to carry out strategies focused on telling your newsroom’s story, engaging authentically, and deploying your fans in a measured way, they likely wouldn’t have thought to put it on air. “That transparency piece…really helped set the table for what we were trying to do,” Canan said. “Ultimately, I think our series was better received by even skeptical audience members.”

WCPO is one of thirty newsrooms signed up with Trusting News in its second round of experimentation with trust-building strategies, currently testing and analyzing seven methods for increasing transparency and building respect on both sides of the reporting process. The first round kicked off in the spring of 2016, as 14 newsrooms (including WCPO) pledged to use social media to build trust by adopting specific guidelines Mayer researched and developed. The project also recruited newsrooms to solicit feedback via a survey — which received 8,700 responses across 28 newsrooms — and then meet in person with a representative slice of the respondents to talk about their feedback.

With two-thirds of respondents to an international survey citing concerns of bias, spin, and hidden agendas as reasons why they often don’t trust news outlets, national outlets like The Washington Post have taken steps to increase understanding. Local news has a wee bit of an edge over national news in (still-low) trust polls, and Trusting News primarily works with local news organizations, which often drive audience members’ first personal interactions with journalists.

“A lot of what people say they want is what ethical journalists would say they are already doing…The fact that people don’t see that we’re doing it means that we’re not doing our job,” said Mayer, who spent two decades reporting in newsrooms and studying engagement at the University of Missouri before launching Trusting News in 2016. “It has to be on us to rebuild that relationship rather than just hoping that if we continue to do good work, they’ll notice it.”

The rebuild has been under heavy construction recently, with initiatives such as the The Trust Project (no relation to Trusting News, works with outlets with more of a global focus, includes tech giants), the Knight Commission (a high-profile group to help inform policy and funding decisions on trust in news), and the News Integrity Initiative (which doles out grants to more projects on increasing trust and inclusivity and decreasing polarization). Trusting News gives attention, not money, to local newsrooms, providing them with tangible, thoroughly researched strategies to implement for real-world testing in a continual cycle of experimentation.Many of the strategies have been implemented through Facebook comments, in addition to broader initiatives such as Canan and Cheatham’s messages introducing the WCPO investigation. Mayer introduced these guidelines before Facebook made them required reading this year with the tweaks to its News Feed affecting publishers and emphasizing “time well spent.” She noted that being responsive to questions and comments on Facebook posts is in line with building engagement and meaningful interactions that Facebook suggested will be boosted with the News Feed changes.

“It’s not so much about gaming Facebook’s algorithm or working with the Facebook changes as much as it is taking advantage of Facebook as a truly social platform,” Mayer said. “Way too many journalists use social media to broadcast rather than being social. Being social involves listening, responding, and adjusting what you’re doing based on the feedback you’re getting…The biggest way newsrooms in this project are having success on Facebook is by participating in the conversations that happen there and using every interaction as an opportunity to explain their credibility.”

For Sarah Binder, working as the community engagement manager at the independently owned Gazette newspaper in Cedar Rapids, Iowa meant leading a culture of engagement experimentation. Binder leads the Iowa Ideas live event series for the Gazette. When the Gazette joined Trusting News, comments on its Facebook post announcing its participation ranged from

“I think sometimes the people who are the most fired up and angry are the loudest and sometimes we just hear those voices,” Binder said. “Those voices are also sometimes the easiest to dismiss because you just think ‘I’m never going to win that person over, they’re never going to want to have a reasonable conversation, they’re just upset.’ But when you see the variations in the responses and see that there is some thought behind some of them…it makes you think about it a little bit more.” (The Gazette responded to the comments with a note about its newest conservative columnist and the fact that its national news comes from wire services.)

“It’s really easy to blow off individual comments,” Mayer added. “But the comments and feedback often add up to really big gaps in understanding.”

Across North America, participating newsrooms range from independent outlets like the Gazette to nonprofits like CALmatters, to startups like Discourse Media, to national brands like USA Today, to broadcast companies like WCPO. (Two of the original testing newsrooms were unable to complete the project after their point people left for other jobs or had reassigned responsibilities.) The top-line findings of the first round of testing, in 2016, found that participating newsrooms had best results when social posts “read like they were written by real people,” “invited people to be their best selves,” and “were framed around what the organization could do for the user.”

For the second round of testing, starting in November with additional newsrooms coming on in January, Mayer fleshed out more strategies and grew the testing group. She wanted to bring in more broadcast voices, considering that a significant portion of the American population gets its news from local TV. So the team added Lynn Walsh, the former president of the Society of Professional Journalists and the then-executive investigative producer for NBC San Diego, to share the broadcast perspective and work with newsrooms to implement the strategies as project manager. Now, the 30 newsrooms are testing seven types of strategies from “showing how you are distinct from ‘the media’” to better labelling stories, for a four-month period ending this spring. Mayer and Walsh will reevaluate the project in the summer and figure out next steps, with potentially a third round of testing. (Interested groups can get in touch with Mayer for more information.)

Binder and WCPO’s Canan both said that the external layer of accountability from Mayer and Walsh encourages creativity, check-ins, and organizational reflections that otherwise likely wouldn’t have happened.

Sarah Walsh, a WCPO digital web editor, noticed a couple of viral videos “making the rounds in our community…that were designed to be inflamed and sensational,” Canan said. Despite viewers sending in the clips, the station decided against covering them because they were “bogus hoaxes.” Instead, Walsh chose to write about the context and facts behind the misleading videos. Readers were impressed: “Good job WCPO!! Way to set the record straight!! And they said journalism is dead, proved em wrong didn’t ya!,” one wrote. Another comment received 73 likes and three love-reactions: “Thanks for doing your job WCPO! Not use to news media taking a step back to investigate anymore.”

“That was literally just one employee having heard about the [Trusting News] project saying this might be something good to do,” Canan said.

Canan left the WCPO newsroom in January to work as Scripps’ senior director of content strategy and has encouraged other stations to integrate journalistic accountability and trusting news strategies. “People are hungry for this,” he said.

In Binder’s month and a half with Trusting News, “we have seen those small wins [through] the commitment to keep doing those steps and keep experimenting. Maybe over time, the small wins add up to something bigger,” she said.

And Mayer wants to keep the momentum going: “We would love for newsrooms to steal as many as these strategies as possible.”