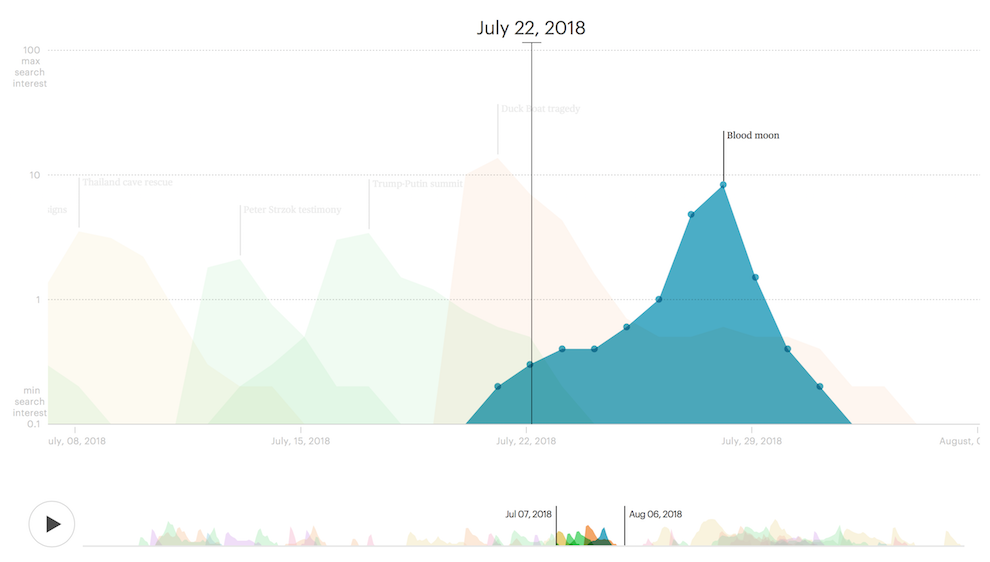

Remember the great blood moon of 2018? Not the one a few days ago, the one last July. Yeah, me neither.

Google Trends, the data visualization firm Schema, and Axios partnered on a collaboration to show how long various news events stayed in the American consciousness in 2018, as evidenced by Google searches. A finding that will not be surprising to anyone who had completely forgotten about that Hawaii false missile alert until they read this sentence is that “the news cycles for some of the biggest moments of 2018 only lasted for a median of seven days — from the very beginning of higher-than-normal interest until the Google searches fizzled out.” And honestly, even seven days seems surprisingly long — you only get there by including big sustained stories like the Brett Kavanaugh nomination and the midterm elections.

(Though that blood moon somehow stuck around somewhere in the semi-sentient periphery of our collective consciousness for 11 full days, it seems. Not much else going on in late July.)

Some events — Stormy Daniels, the Capitol Gazette shooting — petered out much more quickly, and “Hurricane Michael and Hurricane Florence tied for the events with the most overall search traffic.”

Is seven days long or short? Pretty much impossible to say, given the non-scientific sampling of stories here. These aren’t average stories; they’re stories picked because they had outsized impact and staying power. So just go look at the pretty pictures and relax about science, it’s Friday.

Meanwhile, a few things past research has told us about news cycles and lifespans:

— Bad news seems to go away faster than good news, according to a group of Cornell researchers looking at tweets in 2011:

We find that the rapidly-fading information contains significantly more words related to negative emotion, actions, and more complicated cognitive processes, whereas the persistent information contains more words related to positive emotion, leisure, and lifestyle.

— Mainstream media and blogs trade off focus on a particular story in a “heartbeat-like pattern,” according to this paper out of Cornell and Stanford. (They were studying stories in 2008, a long-ago age when blogs still roamed the earth. We wrote about this paper back in 2009.)

We find that the peak of news-media attention of a phrase typically comes 2.5 hours earlier than the peak attention of the blogosphere. Moreover, if we look at the proportion of phrase mentions in blogs in a few-hour window around the peak, it displays a characteristic “heartbeat”-type shape as the meme bounces between mainstream media and blogs. We further break down the analysis to the level of individual blogs and news sources, characterizing the typical amount by which each source leads or lags the overall peak. Among the “fastest” sources we find a number of popular political blogs; this measure thus suggests a way of identifying sites that are regularly far ahead of the bulk of media attention to a topic.

— You can figure out the eventual reach of an individual story much more effectively by looking at social media reactions than pageviews, according to this 2014 Qatar/MIT/Carnegie Mellon study (coauthored by our old friend Matt Stempeck):

We describe the interplay between website visitation patterns and social media reactions to news content…We also find that social media reactions can help predict future visitation patterns early and accurately. We validate our methods using qualitative analysis as well as quantitative analysis on data from a large international news network, for a set of articles generating more than 3,000,000 visits and 200,000 social media reactions. We show that it is possible to model accurately the overall traffic articles will ultimately receive by observing the first ten to twenty minutes of social media reactions. Achieving the same prediction accuracy with visits alone would require to wait for three hours of data.

— You shouldn’t focus only on the speed-centric elements of the news cycle, this 2015 piece by Matthew Ricketson argues, as tempting as that is. Book-length journalism can also impact news cycles on a different timescale:

The imperative on speed in the news media, combined with the inverted pyramid form of news writing, have well-documented strengths, enabling important information to be communicated quickly and clearly. A preoccupation with this part of journalism practice, however, within the news media industry and among scholars, obscures what James Carey has called the “curriculum of journalism.” To be properly understood, Carey argued journalism needs to be examined as a corpus that includes a wide range of materials extending to book-length journalism. Longer articles and book-length works add substantially to the store of relevant and newsworthy information. They also significantly enlarge public understanding of people, events and issues of the day by exploring them in depth, usually by taking a narrative approach in the writing. This article brings to the fore the contribution of these slower forms of journalism by examining immediate and longer-term coverage of two historic news events: the dropping of the first atomic bomb, at Hiroshima in 1945, and the invasion of Iraq by United States-led forces in 2003.

4 comments:

Fashionable dating platforms offer every opportunity to create a serious relationship: detailed profiles, picture albums, chat, email service, video calls, sending real gifts, and even organizing conferences. In addition to that, free membership permits users to take part in video streams and to ask questions in the final chat. Good free courting sites encompass parts that you simply yourself solely know. The person-friendly interface, nice design, and plenty of free features make it a perfect choice for everybody who wants to search out love. Who likes to speak about this stuff anyway? The right way to know if a Chinese language Woman Likes You? What features you don’t know concerning the woman you might be about to meet? Charming single women register on different dating companies to satisfy and date foreign guys and create their own love stories online. In spite of everything these steps, her profile is added to the database, and she will be able to begin her searches, chat, and date foreign males. You’ll be able to meet her in a park, have a romantic dinner, go to a cinema, visit a museum, dance or do sports activities together with her and play in an amusement park. That is one other top webpage where guys meet 1000’s of Asian brides.

Listed below are thousands of verified profiles and a huge quantity of information for every person. The content of the oracle bone inscriptions could be very wealthy, recording meteorology, astronomy, the calendar, geography, politics, economy, tradition, agriculture, conflict, religion, sacrifice, illness, disasters and different data. The recording function of oracle bone inscriptions reflects that characters had been already properly-known and extensively used. The characters have been usually inscribed on tortoise shells or animal bones, giving rise to the term ‘oracle bone inscriptions’. Greater than 4500 characters have been used on these oracle bone items, of which 1500 might be understood and skim by specialists. What impresses me is the Expertise Center, having skilled relationship consultants for any dating difficulties. It’s also my prior consideration begin dating Chinese girls on ChnLove! In 2010 her half-sister Claire Burdis gave a chilling insight into how the romance had begin. Zi Qi and Xing Ren, despite their constant bickering, regularly notice they care for each other and begin relationship.

Via Chinese dating platforms, customers get so many first-class options. On ChnLove, there may be particular part named “Suggestions & Advice” to assist men get a smooth, safe and completely happy relationship expertise by helpful ideas and advice. Right here ou can go to the tombs of the previous emperors, these because the Thien Mu Pagoda, courting once more to 1602 and stroll by way of its graceful gardens. Then you are able to do your factor. Then a primary date will likely be the start of ice breaking. Other readings, nonetheless, decided that exact date and even an exact time of the marriage needed to be prescribed. I did have many worries; nevertheless, ChnLove removes them all by robust evidences and reliable methods in opposition to on-line dating fraud. Relationship Chinese language ladies for marriage is a great expertise, however it is still about constructing a relationship with someone from one other tradition. The opposite great trait of a Chinese language mail order spouse is that she is highly prone to [url=https://chnlovephone.wordpress.com/]chnlove.com[/url] have excellent manners. Due to this fact, religion is absolutely of great importance to them. In 1899, Wang Yinrong, a scholar and high-ranking official of the Qing Dynasty, observed the strange patterns carved on the bones when he took some medicine. Within the late Qing Dynasty, the farmers of Xiaotun Village of Anyang usually turned up previous tortoise shells and animal bones inscribed with strange patterns whereas they ploughed their fields.

Nonetheless, in previous Vietnamese language, 7 is pronounced as “That”, which is similar spelling and identical sound because the phrase “Misplaced” or “Lacking” in previous Vietnamese language. Quantity four is pronounced as “Tu” within the old Vietnamese language system which sounds nearly like “Tu”, which implies Die or Loss of life in the old Vietnamese language that’s closely influenced by the Chinese language. If You’re the One is probably going about to gain much more viewers as the federal government has recently cracked down on entertainment packages, lowering the quantity aired from 126 to 38 each week. Quantity 6 in Cantonese sounds just like the word “Loc” in Vietnamese, which suggests Luck. 10. Don’t take or ask to take issues which can be related to water out of any person’s house such as: bottles of water, water containers, water dispensers, drinking cups, glasses, and many others. Folks usually want each other “Tai Loc Nhu Nuoc” or “Money and success coming in like water”.

I am genuinely grateful to the owner of this web site who has shared this fantastic article

at at this place.

Eastern European folks respect humor so long as it’s backed with good manners. The Golden Rule is: if it appears to be like too good to be true, then it most likely is. Women from Eastern Europe are much like most girls anyplace else. Americans’ clothes choices are usually much more relaxed. That is to say that she’s going to greater than admire the little belongings you do for her that make you look like a gentleman whereas treating her like a lady. When the time to meet your charming Eastern European woman comes, don’t fear: with the help or our companion marriage company, we will assist you throughout your entire keep so you may focus on the objective of your trip and discover out if one of those charming girls can someday be your wife. This means you don’t must waste time with small speak. Finally, don’t overlook to compliment your date. You should really be certain to purchase your date some flowers a minimum of. To make your conversation private, try her profile and ask questions based on what you find. If you find the Ukrainian woman of your selection on any of the websites you will get in contact with them instantly by means of electronic mail.

Give her the selection of restaurant, help her to her seat first, and make sure that she is the primary into the room. It is a great way for a primary date to kick off. East European ladies, as a rule, turn out to be nice wives and loving mothers. Surprisingly enough, European wives are additionally excellent homemakers who see cooking and cleaning not as a chore, but as a method to enhance the lives of their families. More specifically, verify to see in the event that they ‘auto-renew’. Eastern Europeans will appreciate you more if you possibly can show that you’re smart with out being arrogant. Ensure she knows she is primary – They are going to doubtless recognize being treated like they’re the most important particular person to you or are no less than taking precedence. Always put her wants before your individual if you end up in your date, and guantee that she is the one which feels handled effectively if you go out.

There are thousands and thousands of holiday makers come here to go to exotic beaches as well as up to now with lovely babes. You must open doorways for her, carry her baggage, and overall treat her properly. Dating might be an exciting journey stuffed with unique experiences, and for these who are open to exploring international connections, the allure of relationship Eastern European girls is undeniable. 1. Want to satisfy Slavic girls for severe relationships – strive JollyRomance. For this reason, you wish to make it possible for what you choose to do to your date reveals that you are attentive and thoughtful. Make your mind up whether you really want to break up the invoice either, even whether it is extra common exterior of Eastern Europe. Hanging out, sports activities, hobbies, family-women in Europe are brainy in lots of areas. 10.1 We aren’t Answerable for THE CONDUCT OF THE MEMBERS POSTED ON OUR Websites, Whether Online OR OFFLINE. We deal with experiences from members promptly and frequently scan our platform for rip-off accounts and people being dishonest about their relationship status. If you would like to build trust and create a lasting romantic relationship, you must change into willing to place the present romantic relationship before the previous.

Local people need to search out suitable companions. People find Eastern Europeans enticing for several causes together with their unique look, variety character, social nature, and devotion to conventional loyalty. Fortunately they’re very devoted and don’t divorce for minimal reasons. Different European ladies have completely different reasons to seek for relationship and marriage opportunities with American guys. As we reach the top of this guide, it’s vital to keep in mind that whereas [url=https://twitter.com/charmingdatess]charmingdate[/url] the journey of courting a European woman can have its challenges, the rewards are immense. Money talks are regular – At the top of the day, a Slavic lady goes to make her resolution about whether or not she likes you based mostly on your character greater than anything. However, that doesn’t imply that she won’t be preserving mental tabs on what you do throughout the date, how you conduct yourself, and the way you spend your cash. To begin chatting with an Eastern European date, you want to draw their attention by starting the chat by being confident. They are simple to date, however solely if they believe you’re a good man to build a relationship with. These websites are full of potential matches who have an interest find a relationship.

When some one searches for his required thing, so he/she needs to

be available that in detail, thus that thing is maintained over here.

Trackbacks:

Leave a comment