The growing stream of reporting on and data about fake news, misinformation, partisan content, and news literacy is hard to keep up with. This weekly roundup offers the highlights of what you might have missed.

Misinformation in your backyard. A new report from First Draft looks at online misinformation in Colorado, Florida, Michigan, Ohio, and Wisconsin. (The research was supported by Democracy Fund.)

First Draft has collected dozens of examples of information disorder playing out via private Facebook groups, text messaging and other platforms. In an echo of national trends, local influencers and elected officials — state representatives, sheriffs and political candidates — play a key role in amplifying and spreading misleading or harmful information about the pandemic and other issues. Confusion among the public, whether about the process of mail-in voting or the efficacy of mask-wearing, proves fertile ground for creating confusion and encouraging distrust.

The Colorado case study, for instance, looks at claims about voter fraud in mail-in ballots. And in Wisconsin, First Draft looked at conspiracy theories about government surveillance:

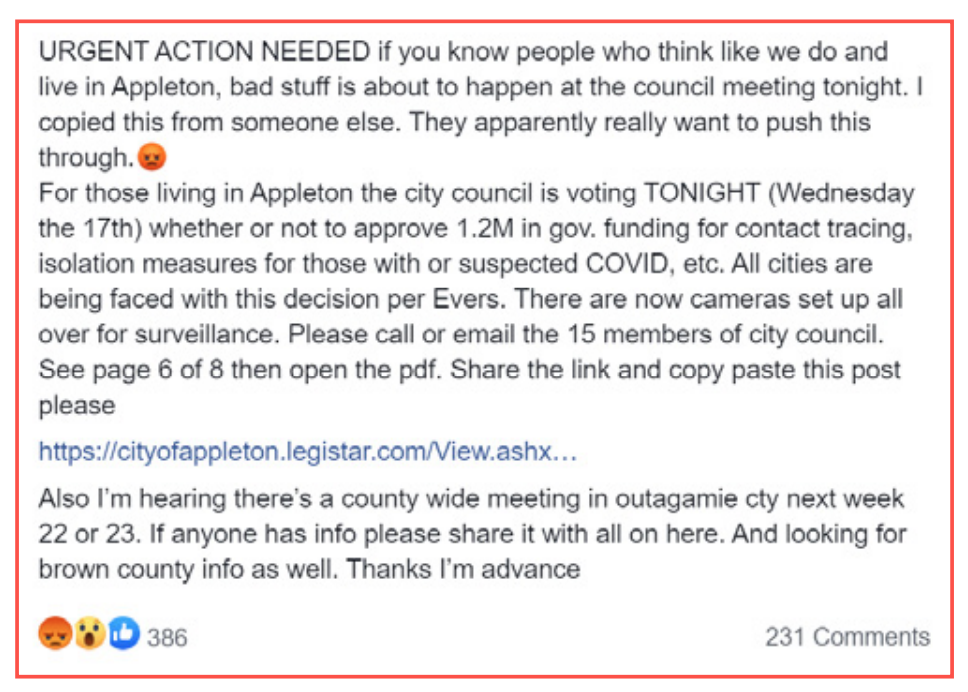

In a Facebook group about reopening Wisconsin, a post encouraged readers to oppose the Appleton Common Council’s acceptance of up to $1.2 million in state reimbursement for its public health response to Covid-19. It warned that “there are now cameras set up all over for surveillance,” drawing hundreds of reactions and comments online. The council received a swarm of questions — including some from people who did not even live in Appleton — about contact tracing and quarantine protocols.

Contact tracing is a disease control strategy that identifies and informs people who have been in contact with someone who has tested positive for Covid-19. Public health experts say that along with widespread testing, it is a crucial part of the strategy for fighting the pandemic. In Wisconsin, the Department of Health Services hired 1,000 tracers to get in touch with people who may have come into contact with the virus and ask them to voluntarily quarantine.

But mistrust of contact tracers rapidly developed on social media. Some theories alleged that Wisconsin Gov. Tony Evers was selling people’s personal information and that tracers were working with Child Protective Services to remove children from homes. As a result, some public health employees have reported threats and harassment on and offline. Because of this, the health department’s logo was removed from its vehicles, according to the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel.

And the Florida case study looked at misleading photos around beach reopenings.

While crowd photos have become a staple of the pandemic, camera angles and other variables mean they are not always accurate depictions of risk. Given what is now known about how Covid-19 is spread, beaches are one of the less risky environments. Yet news outlets continue to use photos of beaches to accompany articles about rising caseloads.

In fact, crowded beach photos have become a staple for news outlets illustrating all kinds of things that aren’t necessarily related to beaches — rising caseloads and super-spreader events, people losing patience with social distancing, etc. It’s become its own public-health-pet-peeve genre on Twitter:

And this isn't about the NYT specifically – it's everywhere. @zeynep has been tracking examples across media outlets in this thread. https://t.co/cJfnXhGxrr

— Julia Marcus, PhD, MPH (@JuliaLMarcus) August 2, 2020

You'd never know from this @WSJ headline and photo that beaches aren't the problem. And if people are going to be blamed for flouting bar guidelines, let's at least come up with ones they *could* follow. Last I checked, you can't drink while masked. https://t.co/dOxzAYwN7Y

— Julia Marcus, PhD, MPH (@JuliaLMarcus) August 2, 2020

This @bloomberg article is… about indoor parties. The photo, on the other hand, is pure misinformation. The people are *outside* in circles, spread apart far more than even the guidelines! What is this media obsession with scolding people doing the right thing? ht @leonhjavi pic.twitter.com/giucryDaY2

— zeynep tufekci (@zeynep) August 4, 2020

The idea that we can merely rely on strengthening traditional media to fight misinformation is naive. No joke. Many top media outlets are engaged in a persistent campaign of visual misinformation (the most powerful kind) about COVID risks (which aren't beaches). h/t @dbchhbr pic.twitter.com/GE4M09DysY

— zeynep tufekci (@zeynep) July 22, 2020

Worried parents are a target for misinformation. Writing in Vox, Katherine Goldstein — creator and host of The Double Shift podcast, a 2017 Nieman Fellow and a mom of three — notes a very specific type of Covid-19 misinformation that’s been circulating in local parent groups — the cut-and-paste, “it’s by a doctor” posts. (I have seen many of these.)

I noticed that people were starting to share ideas and writing and statistics from people they thought had some special insight. There was a cut-and-pasted post, supposedly from an unnamed Covid-19 doctor at Duke University Hospital, about why she wouldn’t risk sending her kids to school, which I later found shared in multiple local Facebook groups. There was a long, ranty post about how we don’t know the long-term health effects of Covid-19. I first saw it shared with no author, and another time it was attributed to Dr. Anthony Fauci, for which I found no evidence.

Then there was a post shared by a Facebook friend who said reading it made her reconsider in-person school. It was written by a public school parent in a neighboring state who didn’t claim to be any kind of expert yet had calculated that if his school district reopened with in-person classes, several hundred students would die of Covid-19. Reading his post, I was both scared and puzzled.

As a journalist and former fact-checker, and as someone who has my local Health and Human Services website bookmarked, I knew something didn’t quite add up. It turns out the problem was his math. He made a bunch of errors in his calculation — the statistical likelihood of a child in his school district dying from Covid-19 was close to zero. I messaged him to point out the error, as did a few other commenters, but he declined to change anything in the post. As of this writing, it’s been shared 24,000 times and has more than 600 comments, with many parents thanking him for opening their eyes to the dangers of in-person school.

“A uniquely regional and religious form of misinformation.” The Oxford Internet Institute’s Mahsa Alimardani and Mona Elswah have a new paper about religious misinformation about Covid-19 in the Middle East and North Africa: “Exploring cases of religious clickbait in the form of false hadiths and viral religious advice from religious figures entrenched in the MENA’s political elite, this essay discusses how new dynamics for religion in the age of the Internet are contributing to a uniquely regional and religious form of misinformation.” For instance, fake scriptures go viral:

Islamic scholars have long dealt with verification within scriptures. Verification of sources is important to preserve the authenticity of the sayings of the Prophet Mohammad. While the Quran and much Islamic scholarship are dedicated to information literacy, a problem of misinformation has riddled Islam for centuries. Among these problems is the spread of “False Hadiths” — fabrications of retellings of the Prophet’s words and deeds. Because of this problem, Hadith scholars have developed rigid methods to ascertain authenticity.A flood of Arabic-speaking YouTube videos prophesized that a divine sound would be heard on the night of the 15th of Ramadan 2020 based on a false Hadith. As the prophecy foretold, the sound would take 70,000 souls and leave 70,000 deaf. The prophecy built its claim on the basis that the rise of COVID-19 is a sign that this is the year in which the sound will be heard. These videos relied on fear to attract Arab YouTube users, who are encouraged by the video creators to share these videos. These videos were viewed millions of times and found their way to other platforms including WhatsApp. The virality and the fear induced by the videos among millions through Arabic-online spheres led the official Egyptian religious entity Al Azhar to release an official statement denouncing the videos as false.

To this date, these clickbait videos are available on YouTube channels and are still able to attract people and earn money. They were able to escape the platforms’ algorithms, and they have not been removed by content moderators. These videos, as like most forms of religious misinformation, seem community-friendly, and to catch their falsehood, a moderator needs to be trained to understand the science of Hadith and the political economy of religious misinformation. These videos — and the majority of religious misinformation — are more likely to live longer on online platforms compared with other forms of misinformation that could be easily debunked.