In 2016, there were more non-voters than voters who cast ballots for either Democrats or Republicans. Who will sit out again this November? A new report exploring the media habits of these non-voters has some answers.

The analysis, released by the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation as part of their 100 Million Project, found non-voters who describe themselves more attentive to news than sports, entertainment, or other types of media are 18 points more likely than other non-voters to say they expect to vote in the presidential election this fall. But where they get their news matters. Non-voters who are primarily newspaper readers are 25 points more likely to say that they plan to vote than the non-voters who mostly get their news from family and friends.

Left- or right-leaning television news outlets drive even more participation. Non-voters who rely on partisan news outlets, especially ones that cater to conservatives, are more likely to say they’ll cast a ballot in November. (Sixty percent of conservative news-watchers interviewed said they plan to participate in the 2020 election, compared to 53% of liberal news-watchers.)

Newspapers are tied to positive views about civic participation and the efficacy of voting but they’re a top choice for just 7% of non-voters. Instead, non-voters tend to rely on television for news, followed, at a distance, by social media and news websites or apps.

In particular, the report found that two sources of news for non-voters — social media and word of mouth through friends and family — are “consistently tied to lower likelihood of voting in the future, more skeptical views about the efficacy of voting and lower community engagement overall.”

Younger non-voters — those who have yet to reach their 30s — are more likely to receive their news through social media, but these relationships persist even when controlling for age, the authors took care to note.

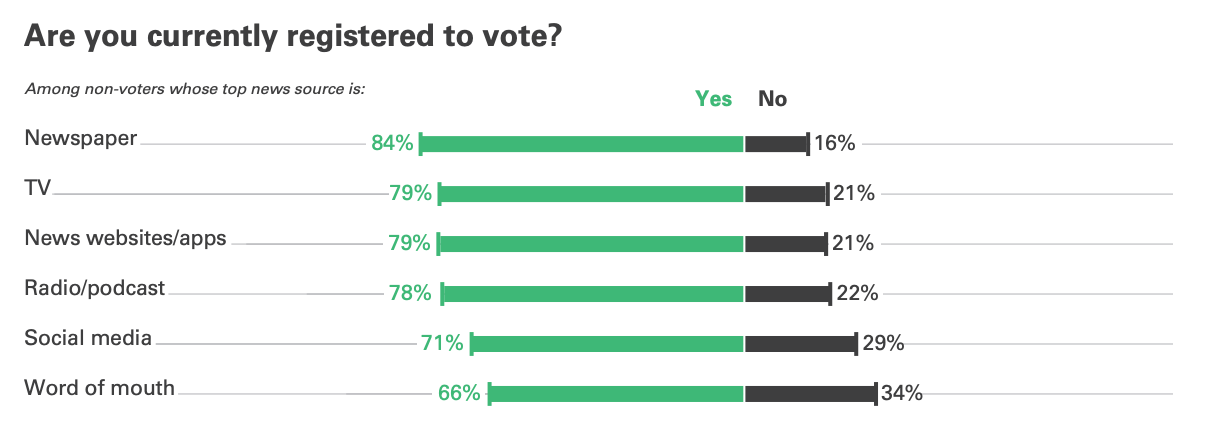

In most states, the first step to participation is registering to vote. (Twenty-one states, as well as the District of Columbia, allow same-day voter registration.) Here, again, those who relied on social media or word of mouth were the least likely to be currently registered to vote.

Also noteworthy? Less than half (46%) of younger non-voters reported actively seeking out news and election information. Instead, a majority of younger non-voters said they’re more likely to “bump into” news. Voters in the same age group, in contrast, are 20 percentage points more likely to say they seek out their news, which is similar to voters in older age groups.

The report’s authors put it this way:

As younger adults and the generations that follow them find their place in a democratic society, the media they consume—driven by social media and their informal networks—is clearly playing a lead role in shaping their political knowledge. It is not yet clear whether or how these media diets will equip Americans on the sidelines to participate in this most critical civic duty.

Both non-voters and voters said they felt more knowledgeable about national affairs than issues and news in their local communities. “The ‘nationally knowledgeable’ members of both groups are more likely to say they’ll vote in the fall, while being less likely, by some measures, to be civically engaged in their local communities,” the analysis noted.

You can read the full report here.

Leave a comment