Good news! Google’s going to spend $1 billion over the next three years paying publishers for their news. Specifically, the money will license publishers’ content for a new feature in Google News called Google News Showcase.

That’s a billion dollars that publishers didn’t have before, and it’s better to have a billion dollars than to not have a billion dollars. (Or so I’m told.) I am squarely in the take-the-money camp here.

But you have to remember: Google’s interactions with the news industry are always fundamentally about its interests, not publishers’.There’s nothing unusual or wrong with that, really; “working to advance your own interests” is a pretty common thread throughout capitalism. It’s what corporations do! But you should keep that in mind before being bowled over by a 10-digit number.

And when a corporate announcement like this seems to make no sense at all from a straight profit-and-loss perspective, it’s probably about meeting a deeper need somewhere else — in this case, Google’s need to be beloved enough to remain underregulated.

As I argued in June — the last time the company got that coveted “Google will start paying publishers for news” headline — the tech giants are generally fine with the idea of writing publishers some big checks. They’ve got the money, after all, and publishers’ complaints about the duopoly are a longtime headache and a PR problem. If Google and Facebook can find a dollar figure that would make that go away, they’ll do it.

The key, though, is that it has to be done on the companies’ terms — not publishers’, and certainly not (shiver) governments’. Here’s what they want:

Google’s announcement today checks all three boxes.

The company is picking what countries it wants to start licensing news in and what publishers it wants to license from. Google News Showcase currently has “nearly 200” publishers in Germany, Brazil, Argentina, Canada, the U.K., and Australia.

In some countries, the announced partners are the big brands you might expect — like Spiegel, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, and Zeit in Germany, or Folha de S. Paolo, Estadão, and UOL in Brazil. In others, though, the choices are a little confusing. In Canada, the launch partners are Narcity Media (owner of a blog about Montreal) and Sault Ste. Marie-based Village Media (owner of 16 hyperlocal sites in Ontario) — but not, say, The Globe and Mail, The Toronto Star, or the major Postmedia regional dailies.

But one thing connects them all: In each of the six countries announced, Google is or has been a target of antitrust efforts or other attempts to rein in its market power.

Google wants it to be clear that it doesn’t consider this money to be compensation for some wrong they’ve done to publishers. (For the record, I think the important “wrong” Google has done to publishers is to outcompete them — make products for advertisers and consumers that both groups find much more compelling than what publishers offer. But most publishers don’t see it that way.) Instead, this is for something new, a fresh chance to make a fresh financial arrangement.

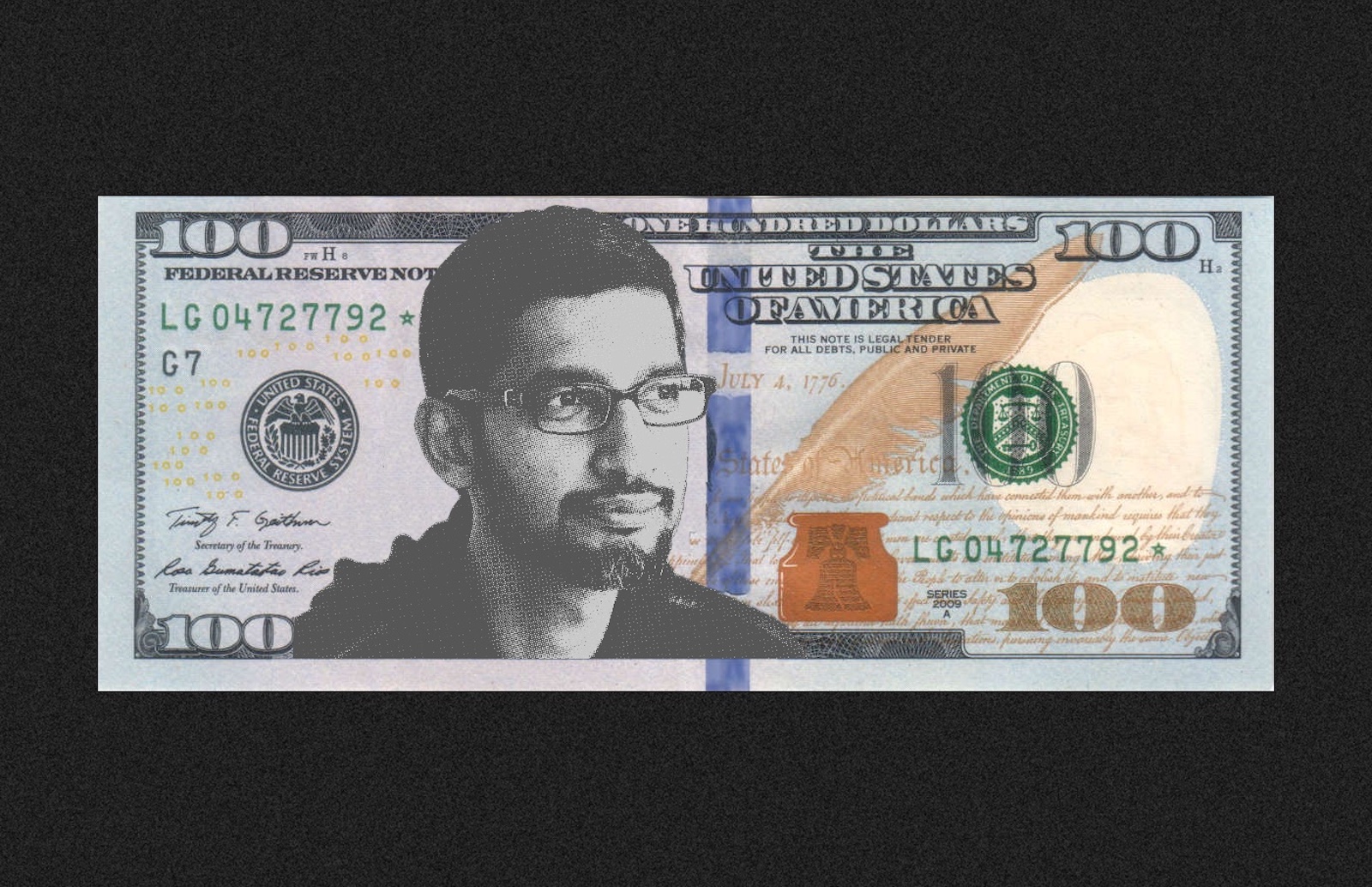

Here’s CEO Sundar Pichai describing Google News Showcase — and, by the way, Pichai being the frontman for this announcement is a good sign of how much PR value Google sees here:

This financial commitment — our biggest to date — will pay publishers to create and curate high-quality content for a different kind of online news experience. Google News Showcase is a new product that will benefit both publishers and readers: It features the editorial curation of award-winning newsrooms to give readers more insight on the stories that matter, and in the process, helps publishers develop deeper relationships with their audiences.

News Showcase is made up of story panels that will appear initially in Google News on Android. The product will launch soon on Google News on iOS, and will come to Google Discover and Search in the future. These panels give participating publishers the ability to package the stories that appear within Google’s news products, providing deeper storytelling and more context through features like timelines, bullets and related articles. Other components like video, audio and daily briefings will come next.

This approach is distinct from our other news products because it leans on the editorial choices individual publishers make about which stories to show readers and how to present them. It will start rolling out today to readers in Brazil and Germany, and will expand to other countries in the coming months where local frameworks support these partnerships.

Here’s what it looks like:

So here’s the thing: Google will make roughly zero dollars off of Google News Showcase.

First: It’s a part of Google News, which runs zero advertising and thus generates zero revenue.1 Google is proud of this fact! It has bragged about it to regulators and publishers when they come sniffing around for money for news.

So even if Google News Showcase is a big hit and it drives a gazillion people to Google News every day, it still won’t make Google any money. (Just as the News Tab won’t make Facebook any money.) And even if spreads to other Google platforms, publisher-curated collections of top stories are never going to be a hugely impactful part of what Google users want. (If someone wants to see what the L.A. Times thinks are its most important stories, they’ll go to latimes.com, or launch its app, or check @latimes on Twitter — not go figure out whatever tortured search request might pop up these story panels. And in any event, Google only rarely monetizes news-based searches with ads anyway.)

Second: It won’t be a big hit and drive a gazillion people to Google News every day. It’s a module a few screens down in an app on your phone that publishers can choose to do some customizations on. It looks fine! But it doesn’t change the value proposition of Google News in any significant way.

And third: Even if it really, really liked the idea of Google News Showcase, Google wouldn’t have to pay publishers $1 billion to make it happen. Its existing algorithms can assemble a collection of a publication’s best stories and put some nice-looking art on top, all without any human or publisher involvement. The same fair-use rules that apply to the rest of Google News would apply here too.

And if Google really wanted to lean into the slightly more editorial things about Showcase — like pulling out a few bullet points or making a timeline — it could just hire a few editors in each country and have them do it. That’s how Twitter does it with Moments and how Facebook used to do it with Trending. Hiring those people would cost a lot less than $1 billion.

Heck, if Google just gave publishers the tools to highlight whatever work they want to highlight in something like Showcase, I’d bet most publishers would gladly do it for them — for free! (As they did once before, a decade ago.)

So why is Google spending $1 billion on a product that will earn nothing, will be used by only a small fraction of its users, and won’t make reading headlines more than, what, maybe 5% better? Well, remember my third rule of duopoly checks to publishers:

They want the money to earn them happy headlines like “Google Pledges $1 Billion to News Publishers,” get the press off their backs, and ideally lower the heat on calls for government regulation or taxation.

A billion dollars is a nice, big, memorable number. I wouldn’t even be shocked if this idea started with “Let’s give them $1 billion, that’ll sound awesome next time we have to testify before Congress,” with the years, scope, and details worked out backward from there. The money is certainly welcome if you’re a publisher in tough straits. But it won’t change much about any single publisher’s financial fate.

Remember, it’s $1 billion over three years, across the entire planet earth. Newspapers alone are a $94 billion annual business worldwide. Multiply that by three years, and then add in all the broadcasters, magazines, and digital-first publishers who’ll also get some piece of this pie, and pretty soon it becomes clear that $1 billion doesn’t change the industry’s fundamental math. Just as the checks Facebook is writing for its News Tab haven’t.

And Google can afford it. If its revenues keep growing over the next three years at the same rate they have over the past three years, Google will earn something like $632 billion in revenues over that span — about two-thirds of it coming from its advertising business. One billion dollars would be roughly 0.15 percent of that. It’s not nothing, but it’s also nothing that’ll put any strain on future budgets.

But Google’s giant pile of ad dollars is looking mighty appealing to regulators and lawmakers around the world these days, who increasingly see it as a target for healthy taxation. And “Google is hurting our local news providers” is one of the key rhetorical messages of those who want to take some of the company’s money or power away.

In Maryland, for instance, the head of the state senate introduced a bill earlier this year that would hit digital advertising targeted at the state’s residents with an excise tax of up to 10 percent.

(The tax would only apply to companies with total annual of at least $100 million — so it’s meant to go after the coffers of Google, Facebook, and their ilk. But a $100 million cutoff would also mean hitting companies like Tribune Publishing, which owns The Baltimore Sun; before the pandemic hit, Tribune was pulling in around $25 million a quarter in digital ad revenue alone.)

The bill passed the state’s House and Senate — but was vetoed by Maryland Gov. Larry Hogan.

A Nebraska state senator introduced a similar bill that would make digital advertising targeted at Nebraskans subject to state and local sales tax — between 5.5% and 7.5%, depending on the jurisdiction. (The bill hasn’t made much progress.) And groups like Free Press have called for similar taxes on the tech giant’s ad revenue; they suggest a 2% tax that would generate about $1.8 billion a year for an endowment for journalism.

Heck, even a Nobel laureate in economics, Paul Romer, likes the idea:

It is the job of government to prevent a tragedy of the commons. That includes the commons of shared values and norms on which democracy depends. The dominant digital platform companies, including Facebook and Google, make their profits using business models that erode this commons. They have created a haven for dangerous misinformation and hate speech that has undermined trust in democratic institutions. And it is troubling when so much information is controlled by so few companies…

The tax that I propose would be applied to revenue from sales of targeted digital ads, which are the key to the operation of Facebook, Google and the like. At the federal level, Congress could add it as a surcharge to the corporate income tax. At the state level, a legislature could adopt it as a type of sales tax on the revenue a company collects for displaying ads to residents of the state.

Now, none of these has become law, and if one does, it’ll face a variety of legal challenges. Google has good lawyers.

The company has gotten used to governments around the world looking for ways to pull some of its revenues into state coffers. But it’s one thing for those attempts to come in regulation-happy places like Europe or Australia — it’s another for them to come on its American home turf. And the fact that that bill got through Maryland’s legislature probably made the threat of taxation feel a lot more real.

That’s really what this is at its core: a way for Google to send money to publishers in a way that it hopes will address a PR problem and stave off hungry governments. Think about it: This morning was theoretically the debut of a new Google product. But its announcement is filed away in the “Outreach and Initiatives” section of Google’s site — the place where it talks about all the good work it does on climate change and sustainability and helping kids.

What could possibly make a company want to give away 0.15% of its revenue? The threat of someone else taking 10% of it.