After a decade in which hundreds of oddly named ad-tech middlemen squeezed their way into online advertising — each taking a cut that could otherwise have gone to publishers — the theme of the past year-plus has been the tech giants taking back control.

Most recently, the giant taking action was Apple; in April, it instituted a strict new anti-tracking regime on its devices that is making it significantly harder for ad networks to create user profiles for targeted advertising.But the biggest move of all is coming from Google, which controls the antitrust-stimulating triad of the internet’s biggest (a) search engine, (b) advertising business, and (c) web browser. Google has been planning for some time to remove support for third-party cookies, those little bits of code that connect your behavior across many different websites and thus allow shoe retailers to remind you, over and over again, about those Asics you left in your cart. They’re the spine of online advertising’s nervous system, and a bit of a privacy nightmare.

Cookies were set to disappear from Chrome later this year, but today Google moved that date back substantially. Here’s Dieter Bohn at The Verge:

Google is announcing today that it is delaying its plans to phase out third-party cookies in the Chrome browser until 2023, a year or so later than originally planned. Other browsers like Safari and Firefox have already implemented some blocking against third-party tracking cookies, but Chrome is the most-used desktop browser, and so its shift will be more consequential for the ad industry. That’s why the term “cookiepocalypse” has taken hold.

In the blog post announcing the delay, Google says that decision to phase out cookies over a “three-month period” in mid-2023 is “subject to our engagement with the United Kingdom’s Competition and Markets Authority (CMA).” In other words, it is pinning part of the delay on its need to work more closely with regulators to come up with new technologies to replace third-party cookies for use in advertising.

Few will shed tears for Google, but it has found itself in a very difficult place as the sole company that dominates multiple industries: search, ads, and browsers. The more Google cuts off third-party tracking, the more it harms other advertising companies and potentially increases its own dominance in the ad space. The less Google cuts off tracking, the more likely it is to come under fire for not protecting user privacy. And no matter what it does, it will come under heavy fire from regulators, privacy advocates, advertisers, publishers, and anybody else with any kind of stake in the web.

Google’s announcement says it wants “the web community” to “come together to develop a set of open standards to fundamentally enhance privacy on the web…In order to do this, we need to move at a responsible pace. This will allow sufficient time for public discussion on the right solutions, continued engagement with regulators, and for publishers and the advertising industry to migrate their services. This is important to avoid jeopardizing the business models of many web publishers which support freely available content.”

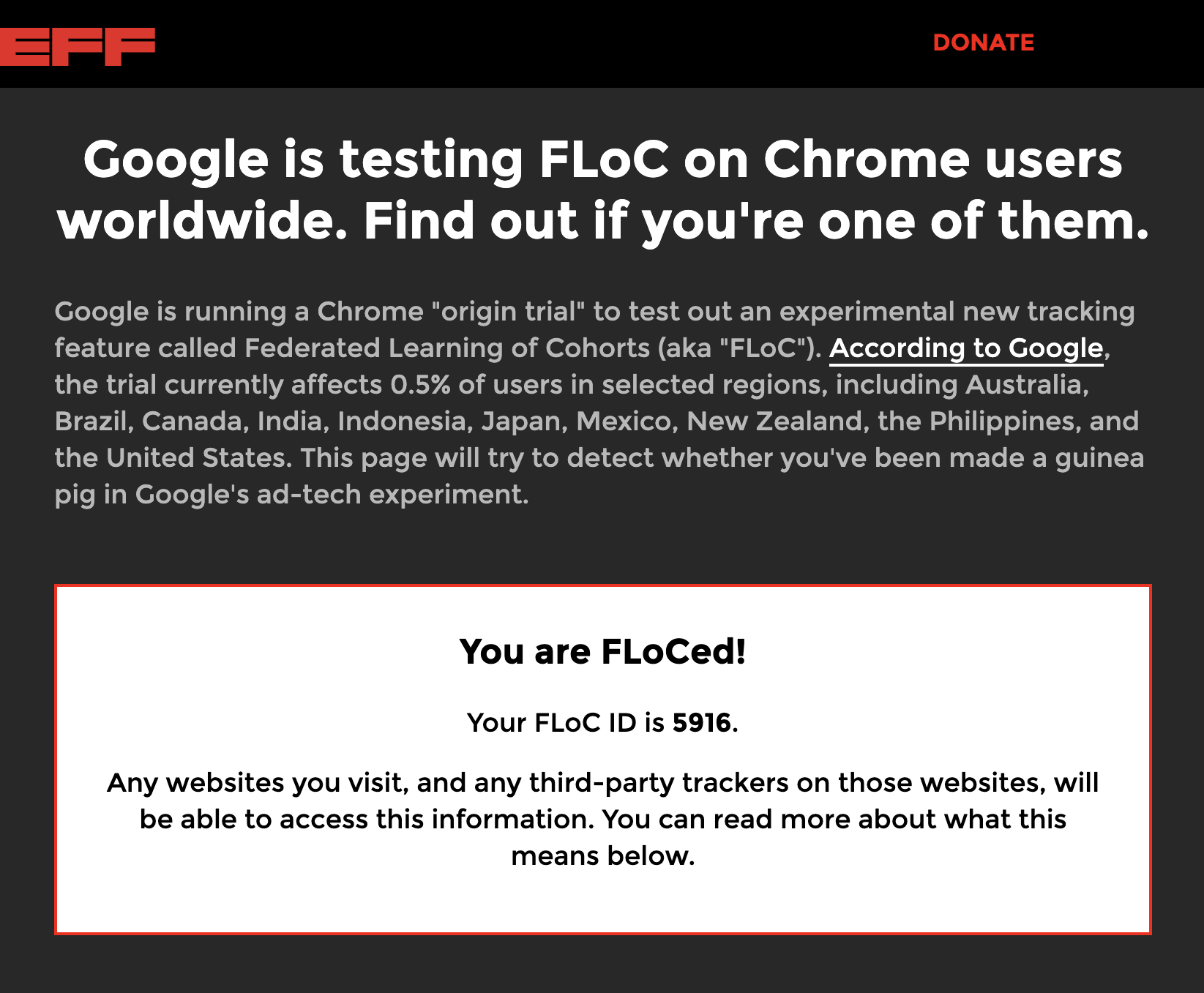

Google’s proposed replacement for third-party cookies thus far has been something called Federated Learning of Cohorts, or FLoC. The idea is to enable some degree of user targeting, but not in ways that rely on personal cross-site-generated profiles. Instead of building an individual user profile by gathering up all of someone’s tracked browsing activity, FLoC uses it to place someone into a “cohort,” a group of “several thousand” internet users with browser activity similar to yours.

So for example, third-party cookies can build a profile of me, Joshua Benton, by tracking all the websites I visit over time, letting advertisers target my interests. FLoC will instead take all that browser data and use it only to determine that I’m a member of FLoC No. 5916. That’s not a guess on my part; I’m apparently one of a small portion of Chrome users being tracked by FLoC now. (You can find out if you’re in that number at the EFF’s charmingly titled site Am I FLoCed?)

So in a FLoC world, an ad unit on a website wouldn’t know that it’s me, Joshua Benton, visiting — only that it’s one of a few thousand people who, presumably, spend a lot of time searching for 19th-century newspaper archives, south Louisiana news stories, old New Orleans Saints stats, and (most important for capitalism’s sake) a new front-loading washer to replace the one that just died.

(Shout out to my fellow 5916ers! Can we all get on a group chat or something?)

Unfortunately for Google, FLoC has not been a hit. Privacy advocates say it doesn’t do enough to limit tracking or discriminatory targeting. All the non-Chrome web browsers of note have said they won’t be implementing it. Amazon, WordPress, and other major players are also blocking or planning to block FLoC, either because of privacy concerns or because they’d like to keep all that sweet, sweet data to themselves.

And FLoC — meant to help solve some of Google’s regulatory problems — instead seems to have generated a new round of them. (While removing third-party cookies would seem to hurt Google, which counts on them to build user profiles for ads, it’ll almost certainly hurt every other ad network and provider more — because Google will still have so much of its own first-party data to use for profiling purposes. Not great when you’re under investigation for your monopolist tendencies.)

Combined with some pretty significant bills to rein in the tech giants advancing in Congress, not the best 24 hours for Google. For publishers, the delay should (should!) give them more time to pursue the best third-party-cookie alternative available to them: building out their own first-party data strategy.