Athens, Greece — We’ve reached “peak news explainer” on TikTok, Sophia Smith Galer said last week at the IMEDD International Journalism Forum in Athens, Greece. To break through on the platform, news outlets and journalists can’t rely exclusively on explainers and reworking existing articles.

Smith Galer was one of three TikTok-focused journalists who spoke about how journalists are experimenting on the platform. She’s a freelance journalist who was most recently a senior correspondent for Vice World News and, before that, was at the BBC. (She found it difficult to “persuade the beeb to see the public service opportunities provided by TikTok,” she tweeted last year, though the BBC now calls TikTok “a crucial platform.”) Smith Galer has more than 500,000 followers on TikTok and more than 15 million likes on her videos.

In her presentation “News outlets are on TikTok, but where are the journalists?” Smith Galer made the case that individual journalists can and should become TikTok creators. Right now, according to a December 2022 report from the Reuters Institute for Journalism, news publishers are generally using TikTok in one of four ways:

What’s missing from the TikTok news landscape and that journalists can lean into is “personality and niche driven, platform-first content with infotainment and awareness at its core,” Smith Galer said.

“I think newsrooms could be doing a lot more to encourage and support their journalists to be…individual journalist creators,” Smith Galer said. “In the way that we have been building communities around our reporters on Twitter, we should be doing the same on the platforms that are the most important places for young people to get their news, information, and entertainment.”

Smith Galer said that the skills and expertise she’s build from creating on TikTok helped be able to grow her audiences on other platforms. Her Instagram following has grown by 30% since June, she said. We’ve reached “peak news explainer,” she said, and audiences want more unique and specialized storytelling.

Her tips for succeeding with journalism on TikTok:

Regularity

- Getting your videos to appear on For You Pages frequently instead of just relying on followers to share

- Returning to your niche and innovating as you develop your niche over time

- Engaging and getting familiar with audiences regularly, both by posting often and participating in the comments section

Originality

- Differentiating TikTok videos from mainstream media by being approachable and personal

- Experiment with original video formats to stand out from other creators and journalists

- Don’t rely on recycling. Film vertically and edit videos with TikTok in mind, instead of reworking existing assets.

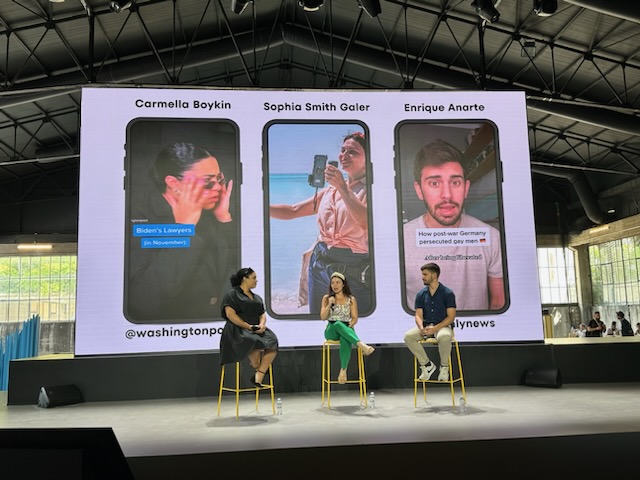

Smith Galer’s presentation was followed by a panel discussion on how news can use TikTok and similar platforms, with Thomson Reuters Foundation TikTok lead Enrique Anarte Lazo and Washington Post TikTok producer Carmella Boykin.

Before she came to the Post, Boykin was a TV news reporter in Rochester, New York. At that time, she started a personal TikTok account where she pulled back the curtain on her job as a reporter. That caught the attention of the Post, where she’s been a TikTok producer since 2021. There are currently two full-time TikTok producers at the Post.

Anarte Lazo started making TikToks for fun in 2020 during the pandemic. Today he runs the TikTok account Openly, the Thomson Reuters Foundation’s vertical about LGBTQ+ rights and issues. There, he is the only video producer for Openly, out of a team of five. He said he relies on the editorial team to fact-check and edit scripts.

In discussing one of the Post’s most viewed TikToks, Boykin explained that a jokey video about scientists’ new images of a black hole engaged and amused audiences because it illustrated the average person’s reaction: the image didn’t really look like anything.

“Audiences really want to see you be a human being,” Boykin said. “It just shows that you can tell information and you can relate to an audience and engage people.”

@washingtonpost The newly processed, sharper image of a black hole, published Thursday in the Astrophysical Journal Letters, used machine learning to fill in a lot of data missing from the original obtained by the Event Horizon Telescope. #blackholesun #blackholes #astronomy #EHT #telescope ♬ original sound – We are a newspaper.

As the only video producer for Openly, Anarte Lazo is charged with developing and publishing content to TikTok, as well as working with editorial teams and encouraging them to use the platform. That work starts with breaking down misconceptions of what TikTok even is.

“The main fear I find when I train people on how to use TikTok is like, ‘I don’t want to dance in my living room, or play with my cat,’” Anarte Lazo said. “You don’t have to only do that. There are lots of ways you can [use it]. You can do explainers, you can be an amazing performer like Carmella. You can also just control the camera and interview [a source].”

Developing content for specific platforms means having to adapt to platform changes and viewers’ interests and patterns. Smith Galer asked the panel about how they see their TikTok content production strategy changing in the future, saying that she herself is starting to prioritize improving her videos’ production value because of the “oversaturation of high quality content on the platform.” She’s also started making longer videos, since TikTok has begun to prioritize them.

Boykin said that she’s working on making her videos accessible on all platforms. She’s found that some videos do well on TikTok but not on platforms like YouTube Shorts, because they might have sounds, features, or references that are unique to TikTok.

“By focusing on more script-based stories, those stories can be published on whatever vertical platform you want,” Boykin said. “You don’t need an entry point or an understanding of the language [of the platform].”

Anarte Lazo said small newsrooms like his will lean into explainers that don’t just tell people the news, but emphasize what impact the news has on their lives. This would also use limited resources in an efficient way.

“We’ll never be as fast or have as [many] resources of a big newsrooms and [some of our] direct competitors, but we have the expertise and we know what the language of the platform is,” Anarte Lazo said. “I think that we, and everyone else that doesn’t have as many resources, will focus on giving people the added value, which is in the end what will actually make a difference.”

The IMEDD International Journalism Forum is hosted by the Greek nonprofit Incubator for Media Education and Development. You can watch the recorded video of this session here and find recordings of all of the sessions here.