When the smoke has finally cleared from the Jill Abramson firing, we’ll be left with one big question: What will The New York Times’ digital future look like under new executive editor Dean Baquet?

The Times’ episodic swan dives into soap opera (the Janet Robinson termination, the controversy around Mark Thompson’s naming, this current exercise in public self-flagellation) provide entertainment for some, but they distract from the bigger questions facing both the Times and our times: how to produce and pay for excellent journalism.

The coincident leak of the Times’ own innovation self-diagnosis provides the first public leadership challenge for Baquet. While some conspiracy theorists postulate that the document might have been released to give cause for Abramson’s firing, the report had been making the rounds since its March 24 publication date, long before the Arthur Sulzberger/Baquet dinner(s) that look like they turned the newsroom tide. But in a sideways way, it does seem to have played a role in the drama, leading Abramson to try to go outside for digital help, a move that may have finally cost her job.

Our question going forward, though, is how much did Sulzberger take digital into account when making his long-simmering, but-still-quick decision on newsroom succession? However they may actually connect in intention, the juxtaposition of the report leak and the leadership switch is hard to ignore.

In the first of several ironies in this story (it deserves its own Times ebook), Sulzberger has managed to choose a newsroom leader who seems to have even less interest in the digital revolution than did the one he fired — one whose insufficient digital leadership is well cataloged, if subtly, in the innovation report. What kind of business partner has Sulzberger hired for his CEO Mark Thompson, whose growth-seeking initiatives are beginning to bear fruit, but which demand a more engaged newsroom?We can wonder whether Arthur and Dean talked in depth about the report — and acting on it — as a top priority. Baquet has said the right things, but his actions will speak louder than those early words. At the same time that he acknowledged the report, his immediate mention of “protection” sent a negative message to those hoping for a newsroom leadership that played more offense and less defense: “The trick of running The New York Times is that you have to keep in mind that it is a very powerful print newspaper with a very appreciative audience. You have to protect that while you go out there and get more readers through other means.”

Hardly a clarion call to embrace the digital reality of the population under 45.

At a time when issues of digital transformation are squarely in front of the paper’s brass, the Times has appointed an editor who is known as a Page One guy — albeit one of the highest caliber. He’s a journalist still immersed in print, less outwardly appreciative of the ability of the Internet to bring the Times younger readers than was his predecessor. No one would call him Digital Dean; he’s more BlackBerry than iOS or Android. Yet when the boss’ son — 33-year-old metro reporter Arthur Gregg Sulzberger — takes the lead in penning a report, and it splashes in the news the same week you win the editorship, you may pay attention to it. As we watch Baquet’s first moves — who does he appoint as managing editor(s)? who will be responsible for digital leadership in the new scheme? — we’ll see the groundwork of the next Times newsroom being laid.

Certainly, the Times overall has been one of the most innovative of newspaper companies. Its digital/all-access model (borrowed and enhanced from the Financial Times model) has spread across the newspaper world, bringing new revenue. Nearly half of American dailies have adopted paywalls in the three-plus years since the Times launched its system; in a business often filled with slow followers, that’s a land-speed record for innovation. Now, it is on to Paywalls 2.0 (“The newsonomics of The New York Times’ Paywalls 2.0”), with NYT Now and Times Premier, among others, and the company is testing newer ground in native ads, content marketing, and the events business.The newsroom, though, isn’t as much a partner — or a leader — in these grow-ourselves-out-of-the-doldrums efforts as it could be. That’s the solid and singular conclusion of the Innovation report. There are bright spots of newsroom innovation, but many self-imposed obstacles throttle it and bottle it up. The report’s plea, made by the crew of younger Times staffers who wrote it: Release the power and energy of Times journalists, so the future can be assured and enjoyed.

What do we know about the context of Baquet and the Times’ recent efforts at newsroom innovation?

It’s best here to first step back into the Bill Keller era, which ran from July 2003 until September 2011, when his managing editor, Abramson, succeeded him. Keller was old school in lots of ways — he liked reading paper in the newsroom — but he knew what he didn’t know about digital disruption. As he often put it, within the newsroom: If the newsroom doesn’t do it, the digital business will be done to us, and the company won’t do it as well without us.

Consequently, Keller put forces of offense into place in the newsroom, Times journalists who “got it.” They included a foursome through which Keller made a statement of intention and change. Jon Landman became deputy managing editor, the newsroom executive for web journalism and manager of the integration of print and web newsrooms for digital. Jim Roberts, assistant managing editor, led the charge, and became a model of social engagement for the Times. Jim Schachter led digital initiatives, including high-profile partnerships with The Texas Tribune and others. Fiona Spruill managed and grew a web staff that grew into the dozens. By all accounts, they collectively made a huge difference in making the Times newsroom more savvy and able to play offense.

All are now gone.

They’ve moved on to other opportunities (Bloomberg, Mashable, WNYC, and Meetup, respectively), but their departures weren’t coincidences. A couple took buyouts, and a couple moved on to greener pastures, all clear on the fact that the Abramson era wouldn’t be a good fit for them.

That three-year Abramson period made some progress in digital, but far less than it could have. While it is undoubtedly true that digital expertise is more common today in newsroom today than five years ago, the lack of go-to, high-level digital leaders is a handicap the report touches on. Of course, “integration” was a watchword of of that newspaper era, at the Times, The Washington Post, and many other papers. The idea: If digital is a big part — and the only growing part — of the news business, then newsrooms needed to think holistically about news, print, and digital. A good idea, conceptually. In execution, the big question has always been how it’s done. At the Times, a lot of digital expertise moved quickly out the door, and highly regarded but print-experienced journalists assumed integrated roles.

One of the Times’ digital newsroom pioneers — Schachter, now vice president for news at public radio station WNYC — offers this perspective on the report and Baquet’s challenge:

The innovation report described the need to rebuild a set of competencies that had been built up under Jon Landman during the Bill Keller era and that was subsequently dismantled. I don’t know if there is any space between Jill and Dean in the decisions that were made to do that, but that’s certainly the newsroom that Dean inherits and situation he confronts.

For Baquet, the next order of business will addressing that report in making key appointments to the masthead. (In this ongoing saga, we’ve heard more about “mastheads” than any time since Moby Dick, which has 83 in total. Maybe all this transition-to-digital angst could be swept away with the invention of a truly digital masthead? Here’s what the Times masthead looks like now.)

Baquet will appoint one or two managing editors. Will they come from the inside or the outside? (Internally, Larry Ingrassia, a deputy managing editor, and Susan Chira, an assistant managing editor, are the two possibilities most mentioned.) What kind of digital knowledge will his deputies possess? Given the clearing out of much of newsroom digital leadership, there’s no obvious inside choice in that regard. Does Baquet go outside?

Irony No. 2, of course, is that Baquet’s ascension was greased, at least, in part by Jill Abramson’s decision to try to hire The Guardian’s U.S. editor Janine Gibson as a second managing editor with digital responsibilities. Here is where the last couple weeks’ events begin to make more sense. Digitally savvy Timesmen and Timeswomen sensed Abramson’s insecurity about digital, an insecurity that they say pushed her more to move away from it than engage its issues. Knowing that the innovation report would be critical of the newsroom’s digital efforts, her efforts, she moved to shore up her weakness, seeking to hire Gibson. That attempt, and how it was made — apparently without informing Baquet — led to the final disagreeable interchange in what had become a disagreeable relationship with her boss.

(As if we needed a third irony, Gibson in turn just hired away the highly regarded Aron Pilhofer from the Times, where he had served as associate managing editor for digital strategy — and the newsroom lead on the spate of recent Times paid niche products. The Guardian named him their executive editor of digital, further depleting the Times’ digital newsroom leadership.)

Want one more? A well-intentioned innovation report — one intended to kick the newsroom into higher digital gear — resulted both in the loss of Abramson and, to a degree, Pilhofer and sullied, though temporarily, a Times brand that has been on a creative and business roll for the past two years, out-innovating its arch-nemesis Rupert Murdoch.Today, that’s all prologue. Dean Baquet, his non-digital cred clear, must figure out a way to make a digital statement. He almost confronted a similar situation at the L.A. Times, when, as top editor, he commissioned a “Manhattan Project” on digital change. Called The Spring Street Project, it later led to a slew of Times changes, but Baquet wasn’t there to put them in place — he’d been fired by Tribune brass for refusing to further cut newsroom staff.

What might Baquet make of the report itself? Its tone is remarkable: bursting with the energy of getting on with the digital transition while also exuding a certain weary enthusiasm. That’s most important.

Its observations are mainly on point and cover a wide range of topics, from understanding audience and the impact of social to attracting and retaining talent, in addition to its profound focus on inter-company relationships. (Beyond its value to the Times, it’s great free consulting for every other newspaper company on the planet. They may laugh at the staffing levels at the Times as they try to figure out how to add an analytics person here or an applications developer there — but the principles highlighted are universal.)

At the same time, as a number of people pointed out to me, most of the recommendations would have been more or less true 10 years ago or five years ago, when a related “Reinventing the Newsroom” document rendered its own introspection.

The report contains some misunderstanding of technological capability and some oversimplification. While drawing good attention to the non-newspaper competition, including The Huffington Post, it fails to contrast the two business models. HuffPo may be growing faster in traffic, but its overall revenue, wholly based on advertising, is still no more than three-quarters of the money that just the Times’ digital-only subscriptions annually generate. The paywall limits traffic to some degree, but it enables the feeding of that well-paid, 1,100-strong newsroom. It’s right in highlighting the Times’ non-print traffic — to which the Times can pay better attention — but it underplays the fact that that print readership, on average, is far more engaged than the average of the 30 million desktop “unique visitors.” Those, though, are minor issues. At best, the perceptive report opens the doors for ongoing and deeper cross-staff tackling of issues.

I won’t go into depth here about the report — the Lab has provided a good synopsis — but we can sum up the issues with four nouns:Leadership: The lack of it is the report’s compelling subtext. On what other journalistic topic would top leadership convene a group of junior journalists to tell it what it ought to do? We have to get beyond the idea that it’s up to “the young people” to show us the way forward; it’s everyone’s charge now. A few newspaper companies have put those with digital savvy in charge of the whole newsroom, but that’s not what the Times has done at this point. Maybe, next time.

“Dean is a phenomenal journalist, but almost by definition he will prove to be a transitional figure,” says Schachter. “He’s got to be the last newspaper guy to run the Times. Who will be his successor?”

Culture: While there’s the beginning of a major change — in the paywall era, journalists better see that they are serving paying readers, print and digital, now — it’s still the print paper that largely defines what gets rewarded and what gets shunned.

Structure: The report doesn’t exactly portray a news operation working in perfect unison, aiming at agreed-upon goals. The rhythms and workflows of the old daily news manufacturing operation are proving to be tenacious. As one Times staffer puts it: “The place is a feudal kingdom of separate desks, each with its own idiosyncratic way of doing things. They all resist grand plans of unification.”

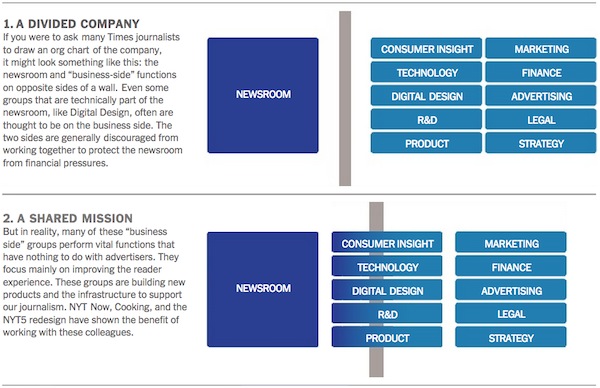

Size: Here we have a funny conundrum: Numerous reports last week mentioned that the Times pays 445 technologists (!), one of the best-kept non-secrets of the Times’ digital reinvention spurt of the last several years. It noted the volume of product (120), analytics (30), and digital design (30) people as well. In a telling graphic (p. 61) the report writers suggest creating a Checkpoint Charlie where newsroom people can benefit from the “shared mission” with parts of the business side, moving past church-and-state metaphors and “a divided company.” Their new plea: Mr. Baquet, tear down these walls.

The issue, beyond leadership, culture, and structure is that size. It’s far easier to launch a Quartz, a Vox, a FiveThirtyEight, or a Business Insider — with far fewer people — and have them work together. Long-established organizational theory tells us people work better (including working through responsibility boundaries) in groups of a dozen or less, with streamlined decision-making. The Times’ bigness — a huge asset in its reporting and its brand’s institutional heft — is a handicap here, a consequence of basic human nature.

As important to our understanding of the Times’ predicament and promise as those four nouns, is one insider’s tale of a news innovation that won wide digital kudos. Producing the product was the easiest part: “It took conversations with about 30 people in the newsroom and on the business side in order to get approval to move forward, and that was before the actual approval meeting,” one former Times staffer remembers. “And even after that, the project almost got killed many times.”

The Times has to address, in the newsroom and throughout CEO Mark Thompson’s business operations, those four issues, identified long ago by, among others, Clay Christensen’s well-touted-in-the-news-industry The Innovator’s Dilemma. Then, it’s all downhill into digital nirvana.Why could it possibly take 30 conversations and multiple approvals to get something good done?

I fear it’s in the very DNA of the Times and good news people everywhere. We are taught to value accuracy — getting it right — above all, and that’s carried over into a digital business environment in which “fail fast” has become the dominant faith. It’s hard to take the offense — and liberate the potential creativity sure to be found among the Times’ thousand-plus journalists — if the mindset is defensive.

We could see in the Abramson to-do — the familiar signs of tension over native advertising, content marketing, and video. That’s not unusual: Like many editors, Abramson’s first instinct, as it seems Baquet’s may be, is to protect, to act as the lead keeper of the flame of editorial credibility. That’s fair as a first instinct; we would expect (and demand) that from the editor of The New York Times. But it’s far too limiting. Defense is insufficient in this age.

Offense — or taking the lead, sometimes with the business side as partners — is clearly what the Times requires.

The innovation report reminded me of, over the past two decades of digital possibility, how many of the best minds in the business I’ve seen drummed out of the news trade in frustration. The print mindset has so dominated that many of the very people who could have eased the industry’s pain are no longer in the “newspaper” business — a diaspora of talent that has only exacerbated newspaper companies’ abilities to reinvent themselves.

And yet, remarkably, they often keep trying. Take David Leonhardt’s new The Upshot, explained in a Q&A here at the Lab last month. Leonhardt won a 2012 Pulitzer for his “graceful” analysis of economic news, and that shines through The Upshot.It gets slotted into the category of “explainer journalism,” though of course Leonhardt, 41, did explainer journalism when Ezra Klein was still in high school. In fact, we could call much of what the Times does explainer journalism. After all, it’s the authority and analysis of the Times that separates it from most of the rest of the too-little-explained world presented by hundreds of other news companies. Yet, as the explainer movement has blossomed, the Times has gotten little credit for what it has long done. The report documents (p. 66) how its development initially didn’t take advantage of what the business side could offer: “Months into the development of [The Upshot], Leonhardt…worried they were neglecting questions surrounding competitive analysis, audience development, platform-specific strategies, promotion, and user testing. But they felt ill-equipped to answer them. ‘I had no idea who to reach out to and it never would have occurred to me to do it,’ Leonhardt said. ‘It would have felt vaguely inappropriate.'”

Contrast that experience with the recent launch of NYT Now (“The newsonomics of NYT Now”). It’s a model of editorial (Cliff Levy)/business (David Perpich, another of the Sulzberger heirs, and head of product) cooperation.One reading of the contrast: Sometimes change is less about grand strategy and much more about a fundamental idea: Do less of this, and more of that.