This week’s essential reads: The key pieces to read this week are David Carr and Ken Doctor on what’s behind the push for big media mergers, John Borthwick on clickbait, sharing, and attention, and David Boardman’s warning to newspaper executives.

Murdoch’s play for Time Warner: Rupert Murdoch’s latest in a long history of big media takeover bids was revealed this when The New York Times reported that his 21st Century Fox made an $80 billion offer for Time Warner that was rejected last month. 21st Century Fox, the entertainment media properties of the former News Corp (Murdoch’s news properties now make up News Corp), would be buying an entertainment company that includes Warner Bros. movies, Turner, and HBO, now shorn of its cable/broadband business and publishing business (which have split off as Time Warner Cable and Time Inc., respectively).

Mashable’s Andy Fixmer, Quartz’s John McDuling, and Bloomberg’s Erik Schatzker and Caitlin McCabe all said HBO is at the center of Fox’s pursuit of Time Warner; it would give Fox one of the world’s premier content properties and, through HBO Go, a major tool to compete with Netflix in the growing streaming video market. Bloomberg said Fox values HBO at $20 billion — a quarter of its total offer for Time Warner. Business Insider’s Jay Yarow argued that Fox’s interest is a bit broader: It wants to gobble up as many valuable TV properties as it can to improve its leverage with TV distributors. At Reuters, however, Jack Shafer was skeptical of the value of the deal for Murdoch, comparing it to the protectionist consolidation of publishers in the 1990s.

Slate’s Jordan Weissmann said the deal may be as simple as Fox digging deeper into a still very profitable business (TV), and asserted that if Murdoch wants Time Warner, he’ll eventually get it. Ad Age’s Simon Dumenco also made that point, declaring Murdoch “untouchable and unstoppable.” USA Today’s Rem Rieder marveled at how Murdoch is bouncing back from News Corp’s phone-hacking scandal. Still, Business Insider’s Hunter Walker noted that antitrust regulators could stand in the way of a potential deal, and The Wall Street Journal’s Keach Hagey looked at what a sale might mean for the Time Warner property CNN, which would be left out of the deal as an antitrust concession.

Whether it’s to Fox or to someone else, Peter Lauria of BuzzFeed argued that Time Warner will sell eventually, since it likely represents the best value for its shareholders at this point. Capital New York’s Alex Weprin broke down several of the other potential buyers, and Peter Kafka of Recode said it will be bought by a company that wants to make a big bet on the pay TV business. The New York Times’ Jonathan Mahler and Emily Steel analyzed the turnaround at Time Warner that’s made the company so attractive.

The New York Times’ David Carr and the Lab’s Ken Doctor both explained the climate of ever-bigger mergers and consolidations that has begun to swirl again around the media industry. They pointed to a couple of major rationales for these defensive moves — size yields negotiating power, and if you can’t beat ’em, buy ’em — and noted that regulators don’t seem to be a big obstacle: “For the most part, the current government has passed on regulating potential monopolies, and as citizens, we have become inured to the consequences of bigness,” Carr wrote.Finally, USA Today’s Michael Wolff and Financial Review’s Neil Chenoweth looked at two behind-the-scenes players on each side who are helping engineer this possible deal: Time Warner’s Gary Ginsberg, in Wolff’s piece, and Fox’s Chase Carey, in Chenoweth’s.

Going beyond clickbait and its backlash: “Clickbait” has been one of this summer’s ongoing topics of discussion in the media world, and The Daily Beast’s Emily Shire examined the anti-clickbait movement — exemplified by The Onion’s Clickhole and Twitter accounts like @SavedYouAClick — as evidence that people are getting wise to the premise of duping and manipulating readers through unnecessarily coy headlines. Vox’s Nilay Patel said clickbait headlines still work (most of the time) because they’re essentially games for the reader to play, and Poynter’s Andrew Beaujon posited that the main problem with clickbait is not the headlines, but the disappointing content that goes with them. “And yet,” he said, “the blame often falls more heavily on marketing than the people churning out stuff that sucks.”

Betaworks CEO John Borthwick provided some data on the connection between attention and sharing that’s the foundation of most clickbait’s popularity, and found that there are many readers who spend very little time on pages after clicking but share the article anyway, sharing essentially based on the headline alone. But beyond those headline-sharers and the people who read on and are disappointed with the content, there are also a significant number of people who spend substantial time reading an article and are also quite likely to share it. Borthwick urged publishers to spend more time attracting those kinds of readers, and Gigaom’s Mathew Ingram described Borthwick’s findings as two versions of the online world: one noisy, fast, and click-driven; and the other deeper, slower, less noticeable, but still widely read and shared.

One of the most prominent sites built around the former model, Upworthy, reported late last week that by far their most viewed, shared, and closely read pieces are not their own editorial content, but their native ads. At Contently, Joe Lazauskas gave a few reasons for Upworthy’s remarkable success with native ads: It likely pays to relentlessly promote those ads on social networks, and the type of blandly feel-good content that makes for the best ads is exactly the same type of content Upworthy’s already producing in its editorial content.

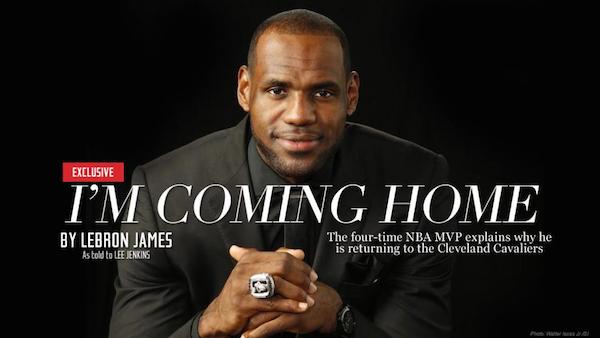

Was SI scooping or suckered?: Sports Illustrated scored the biggest breaking sports news story of the year last Friday when it ran a first-person piece by NBA star LeBron James revealing that he would re-sign with his hometown team, the Cleveland Cavaliers. The essay was written as an as-told-to piece with veteran SI journalist Lee Jenkins. Deadspin, The Wall Street Journal, and the Cleveland Plain Dealer all provided some details about how the story came about: Jenkins got wind of James’ decision on Thursday, pitched a first-person piece to his editors at SI, interviewed James and wrote the piece Thursday night, and handed it off to his editors on Friday. Deadspin reported that the idea for a first-person essay was first proposed by James’ camp, but The New York Times reported that it came from Jenkins.

The Times’ Richard Sandomir criticized SI’s strategy, saying the magazine gave up an opportunity to put some journalistic weight behind a big story. Said Sandomir: “the approach cast Sports Illustrated more as a public-relations ally of James than as the strong journalistic standard-bearer it has been for decades.” In an online chat, The Washington Post’s Gene Weingarten echoed the point, calling it an example of a journalistic mindset in which “being first is overvalued and being good is too often beside the point, or financially imprudent.”

Craig Calcaterra of NBC Sports questioned what exactly Sandomir was expecting SI to add to the story, characterizing it as commodity news as opposed to a substantial story crying out for in-depth reporting. Sandomir, he said, is “fetishizing the business of Serious Journalism at the expense of understanding what sports fans actually care about, appreciating how informed sports fans already are and asserting that the reporter’s highest and best function is to get between fans and the news as opposed to delivering it to them.” Poynter’s Sam Kirkland said it’s still possible for SI to break the story this way and do deeper journalism on it as well. (Jenkins was in Cleveland this week reporting a feature on James’ decision.) And Deadspin’s Kevin Draper looked at the other reporters who scrambled to get this scoop.

Reading roundup: A few other pieces to read from this week:

— Industry analyst Alan Mutter pulled together some simple numbers to remind us just how dire the newspaper industry’s situation is, and Temple University’s David Boardman criticized the Newspaper Association of America’s Carolyn Little’s rosy speech and instead urged newspapers to drop to one day a week in print. Little issued a defense of her picture of the industry.

— The U.S. Federal Communications Commission’s public comment period on its proposed “fast lane” plans for Internet providers was supposed to end on Tuesday, but it was postponed until today because a surge of comments from net neutrality supporters overwhelmed its system. (The FCC passed 1 million comments this week.) The Washington Post’s Brian Fung explained the proposal and backlash, and at The Guardian, Dan Gillmor urged net neutrality advocates to make their voices heard.

— Capital New York’s Joe Pompeo profiled the new Philadelphia-based online local journalism initiative by Washington Post/TBD/Digital First veteran Jim Brady, Brother.ly, and Brady talked with Poynter’s Butch Ward about what he’s learned about local news.

— Finally, Nebraska professor Matt Waite wrote a thoughtful and important piece on the value of doubt in data journalism, with some ideas on how to better incorporate it.