The Knight First Amendment Institute at Columbia University made waves last month when it threatened a First Amendment lawsuit on behalf of users blocked by @realDonaldTrump after criticizing him on Twitter, the U.S. president’s well-used, most-followed Twitter account (more than 33 million followers; official @POTUS has 19 million).

In a letter addressed directly to President Donald J. Trump in early June, Institute director Jameel Jaffer and attorneys Katie Fallow and Alex Abdo had argued that blocking users who criticized or mocked Trump from accessing and engaging with his Twitter is actually unconstitutional, because @realDonaldTrump is used in such a way that it counts as a public forum under the First Amendment.

Today, the Institute followed through, filing a suit in the Southern District of New York. (The official complaint is here; in addition to Trump, beleaguered press secretary Sean Spicer and White House social media director Dan Scavino are named as defendants in their “official capacities.”)

“Legislators and public officials all over the country are increasingly using social media to engage with their constituents. So we really see these questions as the social media-era equivalent of the town hall and city council meeting questions that came up 20, 30, 40 years ago,” Jaffer told me in an interview last month, before the suit had been filed. “It really does affect the vitality of our democracy if local politicians are blocking their critics on Twitter and thereby preventing those critics from engaging with the public officials who are supposed to be representing them.”

“Legislators and public officials all over the country are increasingly using social media to engage with their constituents. So we really see these questions as the social media-era equivalent of the town hall and city council meeting questions that came up 20, 30, 40 years ago,” Jaffer told me in an interview last month, before the suit had been filed. “It really does affect the vitality of our democracy if local politicians are blocking their critics on Twitter and thereby preventing those critics from engaging with the public officials who are supposed to be representing them.”

My use of social media is not Presidential – it’s MODERN DAY PRESIDENTIAL. Make America Great Again!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) July 1, 2017

This tweet will be inconvenient for those still maintaining that this account, @realDonaldTrump, isn't subject to the First Amendment. https://t.co/pYiNz8Zk3K

— Jameel Jaffer (@JameelJaffer) July 2, 2017

The Institute is a new partnership between the Knight Foundation and Columbia University, each of which committed $30 million ($5 million for operating, $25 million for endowment), for a total of $60 million to start. Beyond the splash it made with Trump Twitter-blocking, the Institute is already deep into several other cases that it sees as having far-reaching, law-shaping effects in the digital age, including a FOIA lawsuit against the Department of Homeland Security for records on searches of cellphones and laptops at the border.

Below is a lightly edited and condensed transcript of my conversation with Jaffer about where these cases are headed, the Institute’s larger mandate, and what other cases it might be looking at.

We have a lawsuit relating to searches of electronic devices at the border. We have a suit relating to the White House’s refusal to relate visitor logs. We’re going to argue a case in a few weeks involving the withholding of Office of Legal Counsel memos under the Freedom of Information Act.

Some of the more complex cases might be in front of a district court for six months or nine months or even a year, and then go up to an appellate court, and from there, possibly to the Supreme Court. The life of a typical case that goes all the way up to the Supreme Court is probably five or six years, and sometimes longer.

One is government transparency. The case related to White House visitor logs, and the case I mentioned relating to Office of Legal Counsel memos, fall into that category. The second category is First Amendment limits on government surveillance power, our case involving electronic devices at the border falls into that category.

The third priority is free speech on social media. The Trump Twitter account project falls into that particular priority. Those are priorities we set with our board back in January before we began to build a litigation docket. The litigation docket we have begun to build reflects those priorities.

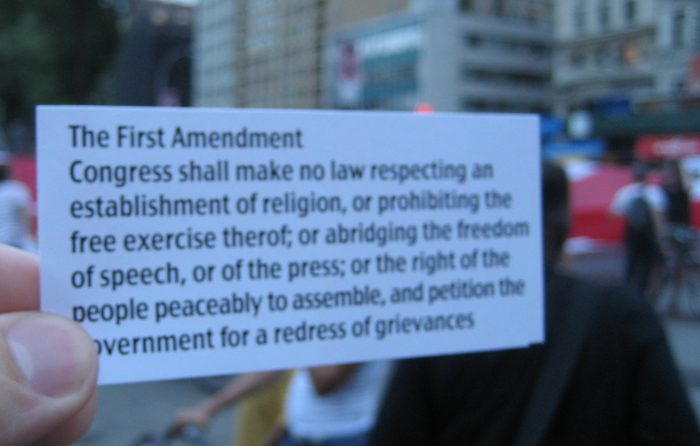

The Supreme Court has held that there are certain forums that the First Amendment recognizes as public forums, like town halls and open city council meetings. The rule at those kinds of forums is that the government can’t exclude people based on their political views. That’s probably the most well-settled rule in First Amendment jurisprudence: the rule against viewpoint discrimination. That rule is very well settled, but how it applies — or whether it applies — to new communications platforms like Twitter or Facebook is an open question. That’s not something that’s really been litigated before.

Legislators and public officials all over the country are increasingly using social media to engage with their constituents. So we really see these questions as the social media-era equivalent of the town hall and city council meeting questions that came up 20, 30, 40 years ago. It really does affect the vitality of our democracy if local politicians are blocking their critics on Twitter and thereby preventing those critics from engaging with the public officials who are supposed to be representing them. That’s why we took on this particular issue.

There are lots of issues that arise out of new technology, including issues relating to government surveillance and the effect of government surveillance on the freedoms of speech and the press, issues like encryption and questions about the First Amendment right to communicate in code — which is essentially what you’re doing when you send an encrypted email or make an encrypted phone call. There are questions relating to the liability of speech intermediaries like Twitter or Facebook: So if you post something on Facebook that’s defamatory, can Facebook be held liable? Or if you post something on Twitter that encourages somebody else to carry out some criminal act, can Twitter be held liable? Those kinds of questions are really important for free speech, because Twitter and Facebook and all these other new social media companies are so crucial now. They are the equivalent to what city sidewalks and streets used to be 50 years ago — those are the places people would congregate to have conversations, and now people congregate on social media.

We’re not making the argument that every social media account run by a public official is a public forum. We’re making the argument that Trump’s Twitter account is a public forum. That has to do with the way Trump uses his account: He uses it to make official announcements, he uses it to engage with foreign leaders, he uses it almost exclusively to comment on government policy. Based on a whole list of factors, we conclude that this is a public forum under the First Amendment.

Those factors may not be present for some other public official. Certainly the basic principle, if we’re successful in establishing that a public official’s social media account can be a public forum for social media purposes, that basic principle would be applicable to other officials and to other social media platforms. But there would still be a factual question in each individual case about whether that particular account was in fact a public forum.

Since our mandate is to defend and strengthen the freedom of the press, I anticipate we’ll end up representing reporters in many of our cases. We do try to look for impact cases. So the idea is to bring the kinds of cases that are likely to have effects for many people, including people who aren’t in front of the court. So we’re unlikely to do run-of-the-mill FOIA litigation, for example, or one-off right-of-access cases. Those are very important cases, but aren’t the kinds of cases we’re set up to litigate. We’re looking for strategic cases, in the sense of cases that will shape the law or change the practices of executive agencies.

We have a research program as part of the center and we’re commissioning essays by legal scholars about matters of public concern — these are essays for a general audience rather than just a legal audience. We’re just about to post one by Thomas Healy — a version of it ran in the Atlantic — about free speech on campus.

We’re open to representing student journalists or working with student journalists. We’re only nine months old, so thus far haven’t had lots of opportunities to do this yet.