Ah, deliverability — the bane of email newsletter producers everywhere.

You’ve worked hard to promote your newsletter, gotten lots of people to sign up, and started dishing out that HTML gold. But even if your email gets delivered — where does it get delivered to, exactly? Did it get stuck in a spam filter? Locked in a digital quarantine, set to be released too late to be useful? Or if it reaches the inbox, which inbox? “Focused,” or the dreaded “Other”? Or, for the bazillion Gmail users out there, has it been declared a mere “Promotion” or “Update”?

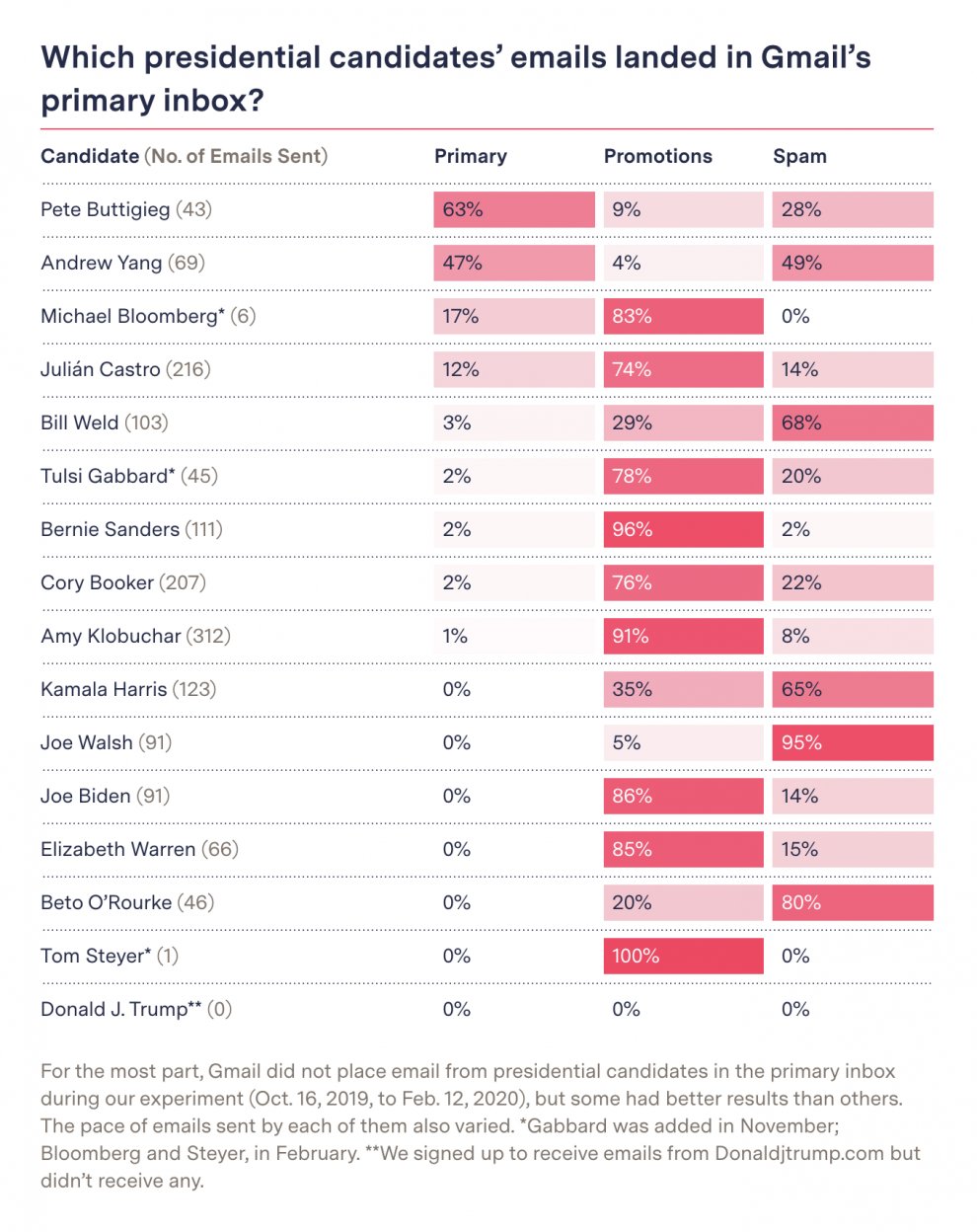

Newly launched The Markup wants you to know: You’re not alone.Reporters Adrianne Jeffries, Leon Yin, and Surya Mattu ran an experiment to see how Gmail dealt with one important category of messages: emails from presidential candidates or other political groups. And they found some very wide disparities:

The Markup set up a new Gmail account to find out how the company filters political email from candidates, think tanks, advocacy groups, and nonprofits.

We found that few of the emails we’d signed up to receive — 11 percent — made it to the primary inbox, the first one a user sees when opening Gmail and the one the company says is “for the mail you really, really want.” Half of all emails landed in a tab called “promotions,” which Gmail says is for “deals, offers, and other marketing emails.” Gmail sent another 40 percent to spam.

For political causes and candidates, who get a significant amount of their donations through email, having their messages diverted into less-visible tabs or spam can have profound effects. “The fact that Gmail has so much control over our democracy and what happens and who raises money is frightening,” said Kenneth Pennington, a consultant who worked on Beto O’Rourke’s digital campaign.

Okay, that’s a little overheated even for me, Mr. Pennington. But the really interesting part isn’t just that Gmail sends a lot of emails to Promotions or Spam — it’s that the rates at which it did so differed wildly among candidates and groups.

For example, 63 percent of Pete Buttigieg’s emails and 47 percent of Andrew Yang’s were slotting into the primary inbox — as compared to 2 percent of Bernie Sanders’ and Cory Booker’s, 1 percent of Amy Klobuchar’s, and none of Kamala Harris’, Elizabeth Warren’s, or Joe Biden’s.

That’s a huge and significant gap!

There doesn’t seem to be any clear ideological thread that runs through the senders that Gmail seems to favor (though the conspiracy-friendly will note Buttigieg and Yang each overindexed on Silicon Valley supporters). Among political groups, the conservative American Enterprise Institute and Claremont Institute were top performers — but so were the Democratic Socialists of America and Avaaz. Still, it’s rough to see the extremist John Birch Society (14 percent in primary inbox) have better deliverability than the American Cancer Society (3 percent) or the Sierra Club (0 percent).

Of 44 swing-state House campaigns The Markup tracked, only six of them had even a single email make it to the primary inbox. Equal-opportunity disappointment. (Official House emails from currently elected officials did better — but still suffered a lot of downgrades.)

I’ll note that — unlike, say, a deep statistical analysis into regulated car insurance rates — this is the sort of story you can probably safely try at home, building off The Markup’s recipe. Sign up for the email lists of your local politicians, parties, associations, interest groups — and see what happens. (Personally, I’d love to see someone do the same thing but for news organizations’ newsletters. Does the Quartz Daily Obsession have higher deliverability than, say, The New York Times’ California Today? The Wall Street Journal’s The 10-Point versus Vox Sentences?)

This scale of data is hard to draw any hard conclusions from — other than the noteworthy fact that email newsletters that seem like they should be broadly similar don’t see the same kinds of results once they hit the inbox. (The Markup threw up its hands at the task too: “We did not determine why Gmail categorized certain emails or certain senders’ emails the way that it did.”)

But in the short term, what I hope some enterprising person with time on her hands does next is download gzipped .mbox files — which contain every email The Markup received — and see if you can figure out why, exactly, Mayor Pete beat Bernie 63-0.

Is it all domain-specific factors — like, say, if Buttigieg emails were marked as spam by users far less often, or if they had a stellar open rate, and Gmail adjusted delivery accordingly? In other words, is it all about a sender being rewarded or punished for its past behavior?

Or is it something specific to the emails themselves — the subject lines, the From: field, the structure of the HTML, CAN-SPAM compliance, the length, the file size, or something else in the switched packets themselves?

That could help produce some useful knowledge on how news companies and others can increase deliverability, perhaps beyond what conventional wisdom holds.

Leave a comment