![]() Every Friday, Mark Coddington sums up the week’s top stories about the future of news.

Every Friday, Mark Coddington sums up the week’s top stories about the future of news.

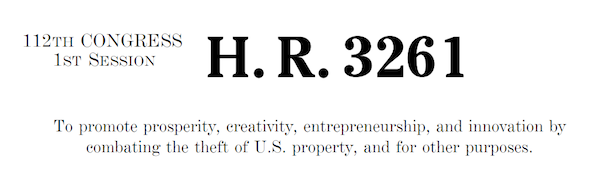

A fight for online freedom: A U.S. House committee hearing brought an important three-week old bill on Internet censorship to the spotlight this week. The Stop Online Piracy Act (a companion of the Senate’s Protect IP Act), would allow content creators to shut down websites on which people hosted unauthorized copyrighted content, or linked to sites that did. The Atlantic has a good, quick explainer, and the advocacy group Fight for the Future has a sharp video illustrating its implications. If you want to go in-depth, Techdirt has the most thorough continuing coverage of the bill.

I’m only slightly exaggerating when I say that it seems as though pretty much everyone on the Internet hates this bill. Bunches of Internet giants oppose it—Google was a major testifier at this week’s hearing (though its rep referenced the WikiLeaks payment blocks favorably, which concerned some)—Tumblr ran an online campaign against the bill by mock-censoring its users’ dashboard screens, and loads of online commentators howled against it.

Here’s why they’re so upset: This bill could inflict a ton of collateral damage, some of which could be a crucial blow to free speech on the web. The New America Foundation’s Rebecca MacKinnon summed up the objections to the bill well, arguing that it would handcuff tech startups, lead to political censorship, and have a chilling effect on speech on the web in general. As Dan Gillmor put it in the Guardian: “The longer-range damage is literally incalculable, because the legislation is aimed at preventing innovation – and speech – that the cartel can’t control. If this law had been passed years ago, YouTube could not exist today in anything remotely like the form it has taken.”

As GigaOM’s Mathew Ingram noted, you can’t have the explosion of creative production, individual empowerment, and democratic potential of the Internet without the downsides of rampant copyright infringement. If you take away the latter, he argued, you take away the former, too. And venture capitalist Brad Burnham made the interesting point that the architecture of the web is based on the assumption that there are more good actors out there than bad, an idea that this bill runs squarely against.

This bill poses some potential problems for journalism, too. Jessica Roy of 10,000 Words outlined some of those issues, pointing out that articles could be censored for linking to sites with piracy information, and that citizen journalism and innovation could be stifled.

Twitter as one-way street: The Pew Research Center’s Project for Excellence in Journalism released a report this week on the way news organizations use Twitter, and the results weren’t pretty: News orgs, they found, were using Twitter predominantly as a way to simply broadcast their stories online, not taking much advantage of Twitter’s interactive capabilities or its ability to link readers to a wide variety of sources. PEJ said the behavior was reminiscent of the link-phobic early days of the web, and the Lab’s Megan Garber called it a “glorified RSS feed.”

GigaOM’s Mathew Ingram was particularly troubled by how little news orgs and their journalists asked readers for news tips and feedback, and media consultant Terry Heaton said this Twitter-as-headline-feed pattern among news orgs is evidence that it really is all about the money. “If influencing public life is the goal, then readership is what matters, and there are many ways to efficiently deliver unbundled content via the Web,” he wrote. “When forcing people to read our content within our infrastructure, then it’s clear that monetizing that content is more important than anything else.” Amy Gahran of the Knight Digital Media Center, meanwhile, tied the study to another Pew study that reinforced the value of personal recommendations over impersonal ones.

There was also quite a bit of talk on Twitter about the study’s weaknesses, led largely by media scholars like USC’s Robert Hernandez. Still, one j-prof, Alfred Hermida of the University of British Columbia, pointed out that this report’s findings do echo those of several previous studies, both academic and professional.

Occupy Wall Street and scooping the wire: New York police swooped in earlier this week to clear Zuccotti Park of Occupy Wall Street protesters, which in itself wasn’t surprising: Similar sweeps have been done in numerous American cities. What drew particular attention among future-of-news folks was the way police did it — by blocking journalists from viewing the action in New York and even arresting 26 of them nationwide, of whom seven worked full-time for traditional news orgs and seven (in New York) had NYPD press credentials. The New York Times and The Atlantic have the most thorough accounts of what went on, and you can check out video of one of the reporter arrests at the Times’ The Local.

One interesting side story to emerge from those arrests began when AP staff members tweeted that their AP colleagues had been arrested before the news hit the wire. The AP sent out a stern memo admonishing its journalists to beat their own wire reports on Twitter, prompting The New York Times’ Brian Stelter to ask, “Shouldn’t the wire speed up?!” GigaOM’s Mathew Ingram said news orgs should consider Twitter the newswire now, and Reuters’ Anthony DeRosa argued that policies like the AP’s (and Reuters’) are the products of head-in-the-sand thinking. (The AP sent out another memo the next day explaining that its initial memo was more about the safety of its arrested reporters than anything.)

Elsewhere in Occupy-related media and tech ideas: The Atlantic’s Alexis Madrigal kicked off a series of posts on technology’s role in the Occupy protests with a creative description of Occupy as a type of API, ReadWriteWeb’s Jon Mitchell praised Storify for its role in Occupy coverage, and New York Times freelancer Natasha Lennard explained why she’s ditching the objectivity-based paradigm of the mainstream media to get involved with Occupy.

Romenesko and online attribution: A few of the loose ends from Jim Romenesko’s unceremonious departure from the Poynter Institute were tied up since last week’s review: Poynter renamed Romenesko’s blog MediaWire, and in an interview, Romenesko shed some light on his insistence on resigning: “I worked there for 12 years, and I’m supposed to spend my final days being supervised, having a babysitter, whatever? It just seemed a little bit humiliating.”

Most notably, the Columbia Journalism Review’s Erika Fry published the article resulting from the reporting that started this bizarre episode. In it, she argued that the attribution problems aren’t limited to Romenesko, but are in part of a function of Poynter’s move to longer — and, as she put it — “over-aggregated” posts. Several Poynter faculty members also weighed in, with Roy Peter Clark providing the sharpest take: “The standards of attribution we still apply in print may in fact be outdated in the age of sampling, file sharing, and mash-ups.”

Other media critics continued to defend Romenesko (Reuters’ Jack Shafer) and rip Poynter (Terry Heaton, Felix Salmon). The Gender Report’s Jasmine Linabary, meanwhile, wondered why we weren’t seeing much attention paid to women commenting on the Romenesko story.

Amazon releases the Kindle Fire: Amazon released its much-anticipated Kindle Fire tablet this week, and the reviews were mixed. (PaidContent has a quick roundup of some of the big reviewers.) It got panned by a few places (most notably Wired), but the general sentiment was that while the Fire can’t match up the iPad and some of the other top-end tablets, it’s still a decent deal at $200. As the New York Times’ David Pogue put it: “The Fire deserves to be a disruptive, gigantic force — it’s a cross between a Kindle and an iPad, a more compact Internet and video viewer at a great price. But at the moment, it needs a lot more polish.”

A few other notes regarding the Fire: Time Inc. had five of its magazines on the Fire at its launch after some protracted negotiating, and Amazon has made the Fire’s source code available to developers to encourage software experimentation. Wired’s Steven Levy, meanwhile, had an in-depth discussion with Amazon’s Jeff Bezos about the state of the company.

Reading roundup: Bunches and bunches of interesting little stories this week. Here are a few we haven’t hit yet:

— A federal judge ruled late last week that Twitter has to hand over information about possible WikiLeaks supporters, one of whom, Icelandic member of Parliament Birgitta Jonsdottir, expressed her outrage in the Guardian over the decision’s threat to civil rights. ReadWriteWeb’s John Paul Titlow and GigaOM’s Mathew Ingram were also among those concerned about the future of privacy online.

— A few advertising-related tidbits: Reuters’ Felix Salmon summarized a fascinating talk he gave on the woeful state of online advertising and what to do about it, Wired looked at Twitter’s efforts to make serendipity pay as an advertising model, and the Lab examined newspapers’ advertising efforts on Twitter. Meanwhile, The New York Times ran an innovative cross-platform interactive ad that also mimicked its news content, which led ACES’ Charles Apple and the Columbia Journalism Review’s Clint Hendler to question its ethics. The Times told Hendler the ad couldn’t realistically be confused with actual Times content.

— The Columbia Journalism Review explored a crucial issue in the changing news ecosystem — what happens to all the communities that aren’t hubs for innovation? — with a series of pieces on Modesto, California.

— Also in CJR, the Lab’s Megan Garber wrote a fascinating article looking back at how journalism has viewed its future over the years. The University of Colorado’s Steve Outing decided to add to that tradition of journalistic fortune-telling with his set of predictions about what online news will look like 20 years from now.

Twitter bird by Matt Hamm and Occupy Wall Street photo by bogieharmond used under a Creative Commons license.