How much can hoax stories and misinformation influence the political opinions of voters, and how much does debunking a false story change someone’s mind?

The answers to those questions remain somewhat unclear. But even if debunking stories moves the needle only a little for voters, any slight interruption to a chain of the sharing of false information on platforms like Facebook is worth it, David Schraven, cofounder and publisher of the investigative nonprofit Correctiv, told me. The outlet, founded in 2014, is Germany’s first nonprofit investigations-focused newsroom, and has published stories on everything from doping and football to superbugs to the fate of the downed Malaysia Airlines Flight 17. It’s also active in involving the interested public directly in its projects.Correctiv is the first organization in Germany to partner with Facebook on its new fact-checking initiative there, unveiled just a month after the U.S. effort launched.

“It’s important for people to be kept informed in the right way,” Schraven said. “Where people are spreading false information from a friend to a friend to a friend, sometimes, if you have someone who breaks that line and says, hey, if you want to pass this information to a friend, please keep in mind that this could be very wrong — I do think this will change things a little bit.”

“Whether it will have an impact on any elections, I don’t know,” he added. (Germany’s general elections are set for the end of September; Angela Merkel will be up for a fourth term.) “But I think it’s worth it. Otherwise, well, I wouldn’t do it.”

Last fall, Schraven had reached out to Facebook to express concern about a spate of hyperpartisan fake news posts, and in December, Facebook asked if Correctiv would be willing to collaborate on a German fact-checking effort. The mechanics of the initiative in Germany operate the same way as they do in the U.S., allowing users to report certain posts as “purposefully deceitful,” and filtering reported links via an algorithm for the staff at Correctiv, who will check what they can on the dashboard Facebook set up. Correctiv is Facebook’s only German partner at the moment, but “we hope to have additional (media) partners on board soon. We will start tests with third parties when they’ve signed on to Poynter’s Code of Principles,” a Facebook spokesperson told me.Correctiv, which prides itself on independence from all governmental and business influences, had to field questions about its new affiliation from concerned readers, some of whom pay monthly donations to be members (its reader FAQ, in German, is included in full below). Schraven emphasized to me that the deal was voluntary, and Correctiv receives no payment or other benefits from Facebook.

“If they want us to do work that we’re not ready to do, we’ll just leave. If they put pressure on us, we can say, we’re done,” he said. “My feeling is that they know that this is a problem, and they are finding a way to solve it. They are taking these things seriously.” Schraven hopes the Facebook fact-checking collaboration will yield some useful data for news outlets and researchers interested in user behaviors on the platform, and that news outlets will eventually be able to unpack the various signals Facebook uses for its “fake news” filter algorithm.

Facebook is by far the most dominant social network in Germany for weekly news consumption. But data on deliberately false or misleading posts masquerading as straight news stories, and how they might influence Facebook users when it comes to real-life civic actions, is patchy. A BuzzFeed News analysis found that anti-Merkel stories from right-wing outlets and fringe fake news sites, for instance, dominated the best-performing posts about Merkel last year: a made-up story about Merkel supposedly taking a selfie with one of the perpetrators of the Brussels terrorist attacks generated far more engagement than the real story of the refugee in the now-famous original selfie photo. (That man, whose image has been circulated on Facebook to illustrate various false reports about terrorism, is now suing Facebook.)

Schraven doesn’t want to underestimate the anti-refugee malevolence in these stories, which often fabricate entire quotes from politicians.

“This ‘news’ is there to influence the political process in Germany, and we think it’s very important to put them straight,” he said, adding that he sees parallels with the “fake news” eruption in the U.S. (or at least the eruption of reporting and commentary on it) across Europe. “In Germany, we also face that problem where people or organizations have been using social media, with very deliberate methods, to disrupt discussions in our society. They are trying to get into our peer-to-peer discussions and interrupt and disturb them, so that the discussion itself becomes impossible, because people are spreading hate and false information. This is a threat to our society.”

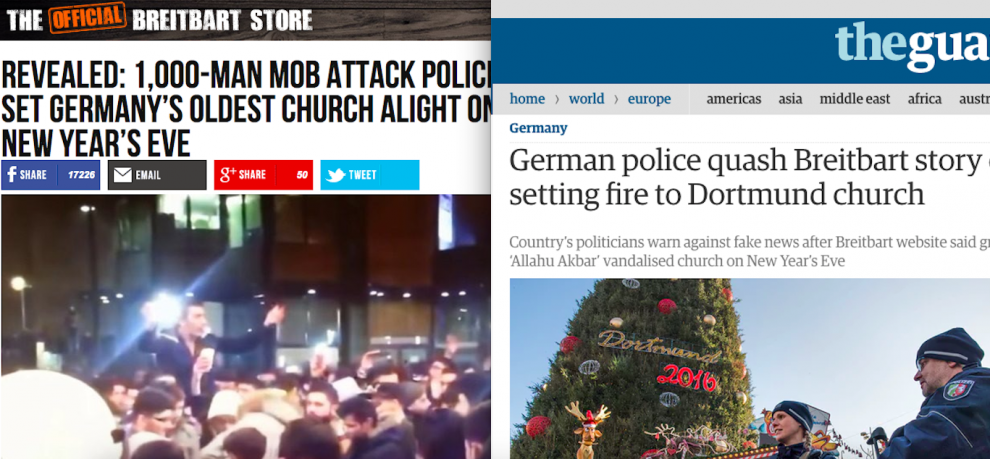

I asked how Correctiv will draw the line when it comes to stories that are hyperpartisan and misleading versus stories that are outright falsehoods. Breitbart News, which already has a London bureau and is trying to push into France and Germany this year, recently published an inflammatory piece claiming a thousand-person mob set fire to Germany’s oldest church during New Year’s Eve celebrations in Dortmund. German police quashed the report, but Breitbart corrected only its claim that the church in question was the “oldest” in Germany, and doubled down on its own story.

Breitbart, Schraven said, knows exactly what it’s doing, and its church fire story is an example of one that should be flagged on Facebook. Dortmund is a town in North Rhine-Westphalia, where critical state elections will be held prior to Germany’s general elections, he pointed out:

“Their story was intended to foster hate in our society, in Dortmund, and in the upcoming election,” Schraven said. “I can see that Breitbart is now starting to be active in Germany. I can see that they’re doing a lot of stories on international politics, they do stories on what is going on ‘the migrant crisis,’ as they call it, and on general politics, like what is going on in Berlin, what Angela Merkel is doing. They know what they are doing, what they have to focus on. Right now they may not have enough staff who can report in German, but it’s not that difficult to establish a German-language service when you know what and where you need to focus your attentions.”

(Google Translate version of English here.)

Bezahle ich als CORRECTIV-Mitglied jetzt die Arbeit für Facebook?

Ein Beispiel: Wenn jemand schreibt, er habe den Eindruck, die Bundesregierung plane aus Hass auf Deutschland einen Bevölkerungstausch, dann ist das zwar Unsinn, aber ein Unsinn, den man hinnehmen muss (weil es eine Meinungsäußerung ist). Wenn jemand aber sagt, es gebe einen Plan der Bundesregierung, die Bevölkerung auszutauschen, dann können wir prüfen, gibt es einen solchen Plan oder gibt es zumindest irgendeinen Hinweis auf einen solchen Plan. Wenn es keinen Plan und keinen Hinweis auf einen solchen Plan geben sollte, würden wir dies schreiben und den Ursprungstext entsprechend markieren. Wir würden ihn nicht löschen. Dann kann sich der Leser selbst eine Meinung bilden, was er für richtig hält. Den Ursprungstext oder unsere Überprüfung.